Photographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images Arthur J Pais

Every 12 years comes a mystical, mind-boggling phenomenon. It is the Maha Kumbh Mela. Harvard experts map the exotic and the mundane at the spectacle. Arthur J Pais reports

With high-powered handheld cameras mounted to a kite and zoomed high in the air, a handful of Harvard students joined Graduate School of Design Professor Rahul Mehrotra at the Maha Kumbh Mela, the mystical, magical and mind-boggling phenomenon, which every 12 years draws over 100 million pilgrims.

There are some experts, including Harvard's business Professor Tarun Khanna, who believe that during the 55-day celebration, about 100 million gather at the Mela.

By those estimates, if the Kumbh were a nation, it would be the 12th most populous in the world.

"When the event ends (with the final bathing day on Mahashivratri March 10), approximately 100 million people would have moved in and out of Allahabad," says Khanna, who played a major role in organising the expedition.

"It took 60 years for the population of Istanbul to grow from 1 million to 10 million, and 50 years in the case of Lagos. At Allahabad, the population rose from zero to 10 million, give or take a few million, in just a week's time."

The Harvard visitors studied how Indian authorities pulled off the creation of a huge temporary tent city with minimal mishap.

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: A father dips his son into the waters of the Sangam during the Maha Kumbh MelaPhotographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Khanna adds on his blog, 'An enormous amount of urban planning, civil engineering, governance and adjudication, and maintenance of public goods -- physical ones like toilets as well as intangibles such as law and order -- and plans to deal with unexpected events goes into the creation of this city. Those are pretty much the main elements surrounding the creation of any city in the world.'

Like some participants in the expedition, Khanna was partially motivated by enlightened self-interest.

As a child growing up in India, he had read about the Mela, but never entertained the idea of visiting it or studying it. After living outside India for over two decades, when he found the opportunity, he was intrigued.

But the powerful urge to map the Kumbh originated from another Harvard professor's interest -- Mehrotra.

"For many years, journalists and writers have been documenting mostly the exotica, the Naga sadhus, women saints and the madness as well as spectacle of the Mela," says Mehrotra, the chair of urban design and planning at Harvard.

"I have for a while now been interested in the phenomenon of temporary urbanism -- the kind of landscape that comprises a large majority of Indian cities. I call Indian cities kinetic cities as their landscape is ever transforming with hawkers, street vendors and festivals."

"The temporality is a useful phenomenon to understand in order to comprehend Indian urbanism. The Kumbh has been an ultimate fantasy from this perspective, and I thought I should go this year. Who knows if I will have the energy to do this after 12 years?"

That personal idea soon turned into a vision of gathering faculty and students in studying the Kumbh.

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

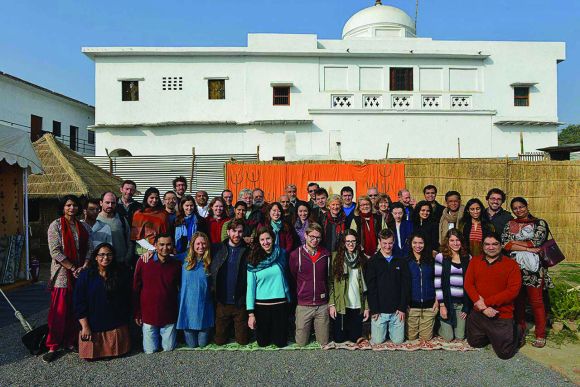

Image: Rahul Mehrotra, second row right, whose brainchild this prject was, and the Harvard GSD Maha Kumbh team -- front row from the left, Namita Dharia, Filipe Vera, Alykhan Mohamed, Oscar Malaspina, and second row from the left, Vineet Diwarkar and James WhittenPhotographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Mehrotra, who joined GSD three years ago, has been taking groups of Harvard students to Mumbai, the city where he was raised, as part of his studio workshop in 'Extreme Urbanism.'

He has been practicing architecture in Mumbai for decades and has a passion for urban preservation and studying the landmarks of the city, including its art deco buildings and movie theatres, and Victorian train stations.

He says the students often arrive with preconceptions of how Mumbai functions and how it should change. So, while the students were from different disciplines they never "transgressed each other's disciplines... siloed in their thinking about a problem for which they had preconceptions."

The Kumbh Mela, he says, "perhaps because it is so vast, temporal and was about massive energy invested in its construction but one that did not leave any trace when it was erased after 55 days was like an out-of-the box problem. To start with it was ripe for inter-disciplinary engagement -- because no one had any preconceptions of what to expect."

He began to realise this would be a laboratory for inter-disciplinary work, because no one -- not even the design students -- had a conception of what the Kumbh is like.

The Kumbh project was going to be mammoth compared to his previous study groups and it was imperative to involve other organizations, especially at Harvard, to make it work.

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: The first group of Harvard students, faculty and staff at the Maha Kumbh mela in January.Photographs: Courtesy The South Asia Institute

Convincing Professor Diana Eck -- a Harvard Divinity School expert on Hinduism and pilgrimages in India -- was a first big step.

He first met her 26 years ago as a GSD student working on sacred towns in India under her supervision.

"She was thrilled at the idea (of mapping the Kumbh). We needed an umbrella organization to make this inter-disciplinary project work," says Mehrotra.

That is why he also took the idea to the South Asia Institute at Harvard where Eck and Mehrotra serve on the steering committee, and got its director, Professor Tarun Khanna, and its associate director, Meena Hewett, involved.

"This project involved many Harvard departments," Mehrotra says, "but it was utterly important that it was carried out under a neutral umbrella organisation. That way none of the organisations involved, including the GSD, would bring its own biases. We wanted to create a neutral approach."

Last fall, Mehrotra and Eck organized an inter-disciplinary seminar on the Kumbh, drawing students from the College, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, HDS, and GSD.

The mantra at the seminar was: 'You are open to everything, because you don't know where to start. That's what makes inter-disciplinary work.'

Mehrotra's idea led to nearly 50 Harvard professors and students -- ranging from history to medicine, urban design, landscape architecture and urban planning to business -- joining the tent city that starts popping up about a month before the pilgrims begin to arrive.

In Mehrotra' words -- "the ultimate pop-up mega city!"

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: Sadhus gesture as one of them holds a "trishul" or trident-shaped weapon after taking a dip during the second "Shahi Snan" (grand bath), of the ongoing Kumbh MelaPhotographs: Adnan Abidi/Reuters

The researchers included Felipe Vera, a Chilean design student and a Fulbright scholar; Christian Blazer, a Swiss architect and colleague of Mehrotra's; acclaimed Indian photographer Dinesh Mehta and his wife, friends of Mehrotra (who were responsible for the camera-on-a-kite plan); Namita Dharia, a Harvard architect student from Delhi, among others from landscape and urban planning and design.

At least one third of the nearly 50 Harvard investigators were of Indian origin.

Some students and professors stayed for a week; some for three weeks.

"Our design team has been monitoring the construction of the city from July when components were being fabricated off site and the Mela authorities were planning," Mehrotra says.

While the Kumbh is often portrayed by the Western media as a mythic spectacle of colourful humanity, Mehrotra and his team were more impressed with the mundane.

The big question, The Harvard Gazette noted, was, 'In a country that can barely keep up with its exploding megacities -- where electricity, clean water, and safety are rarely assured for hundreds of millions -- how does a pop-up tent city manage to run so smoothly?'

They were there to learn from what Mehrotra calls an incredible feat -- "an intersection of the visible, the invisible, the sacred, the profane. Everything is colliding."

"We have tried to map the metabolism of the city," he says.

The team investigated traffic flow, medical record keeping, conservation efforts and daily businesses.

Three students spent days inspecting the toilets, from the modern to hole-in-the mud operations. They called themselves 'Team Toilet' as they worked with Richard Cash, a long-time senior lecturer on global health at Harvard who spends most of the year in India.

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: Pilgrims make their way over pontoon bridges near Sangam, the confluence of the holy rivers Ganga, Yamuna and the mythical Saraswati, during the Maha Kumbh MelaPhotographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Fifteen years ago, Cash organised public health trips to his adopted home country for Harvard students. Eventually, those January outings morphed into a student-led 'toilet mapping project' in Mumbai's slums that have helped local citizens fight for better sanitation.

Public health workers and doctors from the Harvard School of Public Health and the Harvard Medical School found the Kumbh to be a model, servicing people into small areas in the event of a war or natural disaster.

'I think Harvard has a lot to learn (from South Asia),' Hewett of South Asian Initiative told the Harvard Gazette. 'The Kumbh Mela is a microcosm of the region.'

"I think this was an amazing operation to deploy a city at this scale for 55 days!" Mehrotra says, "It is unique in that it is such a large gathering of people, but spatially organised in the way it is with zones and infrastructure that replicate a regular and efficient urban condition."

The organisers deployed infrastructure in terms of roads, electricity, water supply, sanitation and zoning. The humongous organisation of the temporal city could offer lessons for refugee camps anywhere in the world, he believes.

"What struck us the most was the simplicity in terms of layout, but also the diversity and pluralism in terms of subdivisions and occupation that emerged in its final form."

"Most importantly, this is urban imagination of elasticity -- where the system can accommodate from 1 million to 10 million people in a day, yet maintain its basic physical integrity," Mehrotra adds.

He told the Harvard Gazatte, 'What's interesting about the Kumbh is (that) the neutralizing instruments are the grid, the roads, the things that are shared by everyone. But then every akhara is a community of 5,000 to 50,000 people who are allowed individual expression, and they all have their own internal logic in terms of the way they're organised. And that creates a module, a neighbourhood; it creates a sense of community -- which never happens in refugee camps."

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: Devotees bathe in the waters of the holy GangaPhotographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

One of Mehrotra's biggest discoveries at the Kumbh was that it was India's cleanest city, albeit temporary.

"One can argue that this is because it is a short-term preparation in which people band together (like an Indian wedding) to pull it off. But I think the deeper lessons have to do with the thoughtfulness with which social institutions are embedded in the system, infrastructure."

"Distribution in the form of the police areas, fire brigade stations, centres for lost and abandoned children."

"For me this is also a model for public-and-private partnership in city building where the government is focusing on establishing infrastructure (to lead the growth)."

And because the Mela takes place once in 12 years, each time it looks like there is a new generation of pilgrims and this leaves little room for vested interest entrenching themselves, he adds.

Mehrotra believes there is also selflessness at play -- the fact that they can invest so much in something that leaves no physical trace speaks volumes for the power of detachment.

"There is an equitable sense everywhere," he says. "People are not trying to flaunt their wealth and show off their power. There was no fast track to God at the Mela and allowances for the privileged."

...

Inside the ultimate pop-up mega city

Image: Priests perform during an aarti ceremony on the banks of the GangaPhotographs: Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images

Mehrotra and his colleagues admire the way each akhara was allotted space by the Kumbh's administrators before the event began, and each maintained a high degree of control over how it organises its 'neighbourhood.'

Within the blocks or akharas, it is left to individual communities to organise themselves.

In the Juna Akhara area, flashing lights, displays of ornamental weapons garlanded with marigolds, and a crowded network of alleys winding among the tents created a vibe that seemed a world apart from the quiet, sparse, and open space of the ashram next door, the team recalled.

The city's administrators used infrastructure as a way to organize and deploy order in the city, Mehrotra explains, and then they allowed within these blocks 'incredible chaos.'

"And this led to rich variation of visual and organisational expression. Indian cities would become much more efficient, humane and pluralistic if these lessons are imbibed," he says

For the next year, students and professors will write articles, study the statistics and offer solutions to make medical record keeping and traffic conditions more efficient.

They will also look at the train station stampede that killed 36 people during the pilgrimage in February.

Professor Eck, for whom the mission was to look beyond the stereotype, says, "Our concern is to look at this in a much larger context, and not look only at the spectacular and the exotic. The life of this Mela -- as a marketplace, as a place of teaching, of entertainment, of evening performances -- is something that goes on every day."

article