'My message to young middle class Indians who actually have principles and ideals is this: When you think about the future of India, think also of getting involved in politics.'

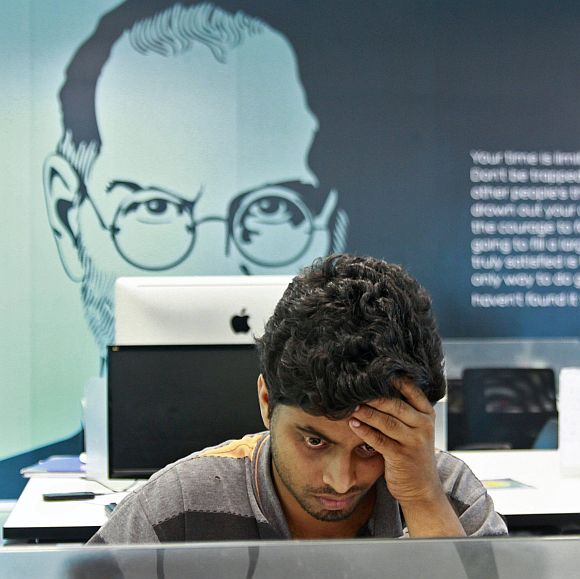

Shashi Tharoor explains why the middle class needs to get involved in politics.

As I reflect on India since 1947, I am conscious that, before I entered politics myself, one of my more frequent laments had been about the abdication by the Indian educated classes of our political responsibility for our own destiny.

My generation grew up in an India where a vast gulf separated those who went into the professions or the civil services, and those who entered politics. The latter, at the risk of simplifying things a bit, were either at the very top or the very bottom: Either maharajahs or big zamindars with a feudal hold on the allegiances of the voters in their districts, or semi-literate ‘lumpens’ with little to lose who got into politics as their only means of self-advancement.

If you belonged to neither category, you studied hard, took your exams, and made a success of your life on merit -- and you steered clear of politics as an activity for those 'other people'.

But the problem with that approach -- while completely understandable in a highly-competitive society where the salaried middle class rarely enjoyed the luxury of being able to take the kind of risks that a political life implied -- was that it left out of Indian politics the very group of people that are the mainstay of politics in other democracies.

...

Around the world, the educated taxpaying middle-classes are normally the ones who bring values and convictions to a country's politics, and who have the most direct stake in questions of what government can and cannot do.

Across Europe, for instance, it's people from the middle class who set the political agenda: they make up the bulk of the activists, voters and candidates for political office.

In most Western democracies, politics is essentially a middle class pursuit.

But in India, our middle class has neither the time for activism (they're too busy doing professional jobs to make ends meet) nor the money or the votes to count in politics. The money flows at the top, and the votes, in our stratified society, lie at the bottom, where the numbers are.

So members of the educated middle class abstain from the process, and all too often look at it with disdain. They don't show up to vote in large numbers; whereas, in the US, the turnout in poor black Harlem in most Presidential elections (barring Obama's) barely exceeds twenty per cent, in India the poor turnout en masse to vote, spending hours in the hot sun to cast their ballots.

They believe, rightly, that their votes make a difference, whereas the middle class disempowers itself by its disdain.

...

No wonder there is so much disenchantment amongst ordinary middle class people with the processes of our democracy, such cynicism about the lack of principle amongst our politicians, and such surprise in learning of an honest politician (because we routinely expect the opposite).

This is easily apparent in the public attitudes of middle class Indians to politics and politicians.

Growing up in India, I was used to a double standard: Most Indians accept, indeed assume, conduct on the part of politicians that we would never condone in our neighbours.

Traditional middle class morality required arranged marriages, marital fidelity, scrupulous honesty and adherence to the law at all times, whereas politicians were expected to be different from the rest of us, and therefore exempt from these norms.

As larger-than-life figures, they enjoyed a societal carte blanche to lie, cheat, dissemble, and commit large-scale duplicity, adultery and tax fraud; only murder was a little more difficult, though even there a handful of major politicians have been released from jail in India after allegations of offenses that might have earned lesser mortals fates worse than death.

So it was with some astonishment that I first went to America and discovered the opposite double-standard in operation: Americans expected, indeed required, conduct on the part of their politicians that they would never have presumed to demand of their neighbours.

...

Middle class Americans, for the most part, lived in an environment of pre-and extra-marital sex, divorce and adultery, and lapped up soap operas and television talk-shows where these were the staple fare. But they expected their politicians to be models of moral rectitude, their CVs punctuated by the standard long-lasting faithful marriage and 2.5 clean-cut children.

At least it meant that they idealised their political leaders; in India, we routinely disparaged them.

The result is that whereas 10 of the last 12 American presidential nominees of the two major US political parties were graduates of either Harvard or Yale, the products of our best educational institutions rarely venture into politics.

In America, the commentator Michael Medved wrote that the skills and determination required to get into Harvard or Yale are in themselves indicators of suitability for high office -- ‘the driven, ferociously focused kids willing to expend the energy and make the sacrifices to conquer our most exclusive universities are among those most likely to enjoy similar success in the even more fiercely fought free-for-all of presidential politics.’

In India, the kids who 'conquer our most exclusive universities' would for the most part consider it beneath themselves to step into the muck and mire of our country’s politics.

The attitude of most Indians is that if you're smart enough to get into a good university, you can make something better of your life in a ‘real’ profession.

Politics, it is generally muttered amongst the middle class, is for those who aren't able to do anything else. And the skills required to thrive in the world of Indian politics have nothing to do with the talents honed by a first-class education.

Can this state of affairs continue indefinitely? No -- and it probably won't.

...

My vision for India in 2020 is of a country growing economically, whose economic transformation brings more and more people into the middle class -- and by 2020, this process may have begun to reach the point where the numbers of the middle-class will indeed begin to matter in elections.

We already have, in the current Parliament, several educated and bright young professionals of the kind of background that for many years previously would not have been found in politics -- people with good degrees, a national vision, international experience, intelligent ideas and the capacity to articulate them.

It doesn't matter that a significant proportion of them are the sons of politicians: The fact that they are in Parliament brings a different standard to bear on the quality of our politics. As they change the public's expectations of what a politicianshould be like, they should be joined by 2020 by many others of similar qualifications but with no political background.

In that, eventually, will lie our democracy’s salvation.

So my message to young middle class Indians who actually have principles and ideals is this: When you think about the future of India, think also of getting involved in politics.

The nation needs you.

Excerpted from India Since 1947, Looking Back at a Modern Nation, edited by Atul Kumar Thakur, Niyogi Books, with the publisher's kind permission.