Photographs: Homai Vyarawalla/Alkazi Collection of Photography Sanchari Bhattacharya

Part I of the interview: 'Gandhi should never have agreed to Partition'

Homai Vyarawalla started her photographic career in Mumbai, the city where she moved to for further studies from her native Navsari in Gujarat. She earned a diploma in art at the prestigious Sir J J School of Arts.

Though she was attracted to painting, she realised soon enough that it would not bring much money. Photography was "something new, something interesting and artistic enough." Plus, it paid well -- she received Re 1 for each of her initial photographs, a good sum those days.

Vyarawalla's photographs of Mumbai -- taken in the late 1930s and early 1940s -- tell the story of a city that still managed to sleep at night, which gave its residents the time and space to catch a breath.

'The city is no longer as nice and clean'

Image: At the Gateway of India in Mumbai during the monsoonPhotographs: Homai Vyarawalla/Alkazi Collection of Photography

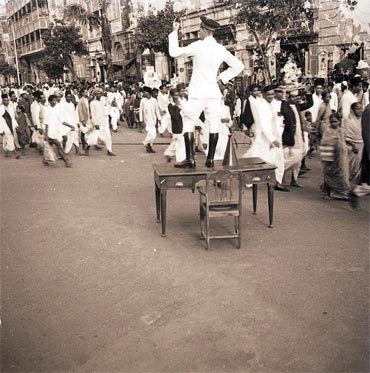

The photographs hark back to a time when the regal Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus was called Victoria Terminus, when traders waited on the streets to catch the sight of a good omen before starting their daily business, when people enjoyed a rain-washed afternoon at the Gateway of India.

Now 97, she misses the "serenity" of the old Mumbai -- the city where she and her husband had celebrated their marriage by having bhel puri at Girgaum Chowpatty on their wedding day.

Mumbai, she feels, "is too overcrowded. The traffic is overwhelmingly slow. There are far too many things for a smaller space. Earlier, the roads used to be washed. The city is no longer as nice and clean."

One of her photographs proves the adage that the more things change, the more they remain the same. It shows harrowed residents in then south Bombay traversing through knee-deep waters, and is not unlike the photographs that appear in newspapers when rains wash away parts of Mumbai each year.

'Her pictures tell a story of the history of time'

Image: Homai Vyarawalla on a shoot in the Chambal valleyPhotographs: Alkazi Collection of Photography

An associate professor at the film school at Delhi's Jamia Milia Islamia University, Gadihoke met Vyarawalla in 1998, while she was making a film about women photographers.

Their friendship culminated in this exhibition, which include many of Vyarawalla's political pictures as well as other lesser known images.

"We have included many photographs of everyday life; they capture the social and cultural history," says Gadihoke.

The exhibition includes several photographs of Vyarawalla at work.

"They are images of a woman in an unconventional profession, notes Gadihoke. "They tell a the story of the history of time."

'I had done enough'

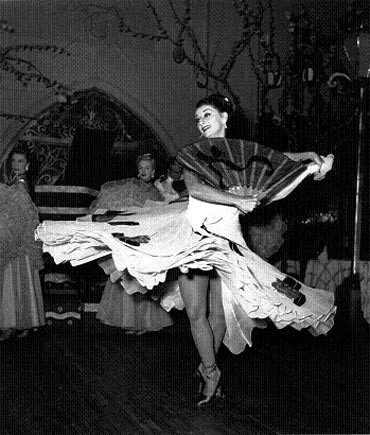

Image: A visiting troupe of dancers in DelhiPhotographs: Homai Vyarawalla/Alkazi Collection of Photography

She has not taken a single photograph in the last 41 years.

"It was not worth it any more," she says, lamenting the "bad behaviour" of the new generation of photographers.

"We had rules for photographers; we even followed a dress code. We treated each other with respect, like colleagues. But then, things changed for the worst. They (the new generation of photographers) were only interested in making a few quick bucks; I didn't want to be part of the crowd any more," she says.

Didn't she miss meeting Presidents and prime ministers, diplomats and bureaucrats? Vyarawalla shakes her head and states, "I thought I had done enough."

'You should live on your own'

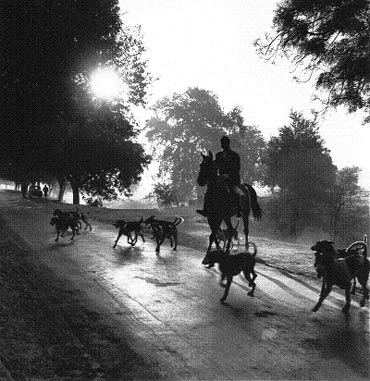

Image: A fox hunt on a cold and misty morning in DelhiPhotographs: Homai Vyarawalla/Alkazi Collection of Photography

A Gandhian at heart, Vyarawalla has imbibed the Mahatma's teachings in her everyday life. She follows a simple, spartan lifestyle in Vadodara, where she has lived in near-anonymity for years.

At 97, Vyarawalla, who lives alone, does all her house work herself. She even makes her own slippers!

"You should live on your own, do your own work. It gives you self satisfaction," she says.

She gives away to charity any extra money she receives from an award or a felicitation.

Homai Vyarawalla also refuses to sell any of her photographs, in spite of being offered extremely handsome prices for some of them.

Instead, she has handed over her entire life's work -- priceless photographs taken between 1937 and 1970 -- to the New Delhi-based Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.

'My photographs will remain after me'

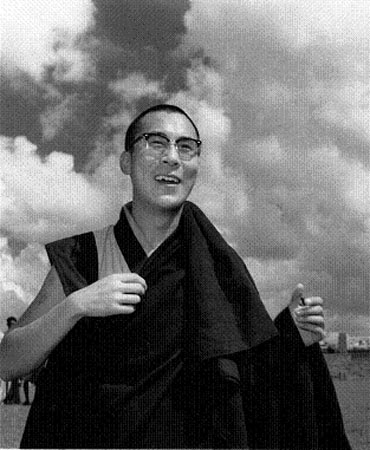

Image: The Dalai Lama during a visit to Sikkim in 1956, three years before he left Tibet foreverPhotographs: Homai Vyarawalla/Alkazi Collection of Photography

In January, an excited neighbour rushed to the nonagenarian's house to inform her that she had been awarded the Padma Vibhushan -- India's second highest civilian honour after the Bharat Ratna.

Hasn't the recognition -- awarded 41 years after she took her last photograph -- come her way a little too late?

With a twinkle in her eye, Vyarawalla counters my cynicism. "Don't go by my age," she says. "Go by the age of my photograph. They will remain after me, they will remain for years."

article