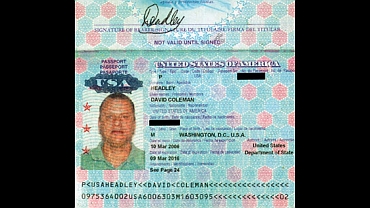

Post 9/11, Lashkar-e-Tayiba operative David Coleman Headley was under the scanner of the US intelligence who believed he was related to a top ISI official. What is shocking is that despite regular tipoffs on Headley, he was given a clean chit time and again by the US, reports ProPublica's Sebastian Rotella in the second of a four-part series

The first part of the series reveals how America botched up chances to nab him.

Chapter 3: Mission in Pakistan?

On September 12, 2001, Lashkar-e-Tayiba operative David Coleman Headley's United States Drug Enforcement Administration handler called him.

Agents were canvassing sources for information on the Al Qaeda attacks of the day before. Headley angrily said he was an American and would have told the agent if he knew anything, according to the senior DEA official.

Headley began collecting counterterror intelligence, according to his testimony. He worked sources in Pakistan by phone, getting numbers for drug traffickers and Islamic extremists, according to his testimony and United States officials. He visited a mosque in Queens at the direction of the DEA, according to his testimony and officials.

But there was a dark side. A former girlfriend of Headley's told a bartender named Terry O'Donnell that he wanted to go to Pakistan to fight alongside Islamic militants, according to law enforcement officials. She said he had praised the Sept 11 attacks, recalled O'Donnell, now a New York firefighter.

"And then she went on and said he was happy to see it happen," O'Donnell said in interview. "And he got off on watching the news over and over again."

O'Donnell contacted a Federal Bureau Investigation-led task force that was investigating 9/11 -- and an avalanche of tips. Residents of the traumatised city were reporting everything from people who spoke Arabic to neighbours who put out the garbage at odd hours. Investigators interviewed Headley's mother and the girlfriend, who described his ideological support for militants in Kashmir, according to officials.

It would be the only warning about Headley that resulted in an interrogation. On Oct 4, two defence department agents working for the task force questioned him in front of his DEA handlers at the drug agency's office, according to the senior DEA official.

Headley denied the accusations and cited his counterterror work, according to US officials. He told the agents he had a distant Pakistani relative who was an army general and the deputy director of the Inter-Services Intelligence, that nation's powerful intelligence service, according to US and Indian officials.

Today, US intelligence believes the relative may have been Gen Faiz Gilani, the ISI's deputy director at the time, according to a US counterterror official. The suspected family connection has not been confirmed, the counterterror official said. But it was a portentous detail.

The investigators cleared Headley. Although their informant had been interviewed by the FBI task force, the DEA handlers did not write a report, the senior DEA official said. In addition, he said the DEA has no record that agents looked into Headley's claim about the ISI relative to determine whether it had intelligence value or, conversely, might show he was a liar.

This story was co-published with PBS FRONTLINE.

...

Six weeks later, another unusual thing happened. A federal judge ended Headley's probation three years early so he could travel to Pakistan. A transcript and accounts of participants show the hearing was rushed. Headley's lawyer told the judge he had "just been handed all sorts of material." A supervisory probation officer, Luis Caso, apologised because he had not had time to dress appropriately for court.

"Having a probation terminated early is rarely done. It's usually reserved for someone who's very ill," Caso said in an interview. "It was a last-minute thing."

The government was in a hurry, said Caso, who is now retired.

"From what I remember, it's basically he was a very good cooperator at that time, working with the DEA, and he was going to do more of the same but overseas in Pakistan," he said. "It was shortly after 9/11 occurred, and at that time, all the federal law enforcement agencies were doing their very best to investigate the terrorist activity, and whoever they had under their control for information purposes they had utilised to the maximum."

Headley's lawyer has a similar recollection. Howard Leader said prosecutors called him a few days earlier to tell him the hearing would take place.

"The fact that this was coming from the government, that was, frankly, highly unusual," Leader said. "It's the only occasion I can recall it ever happening."

Leader said he believed the DEA had made the request and that Headley would continue working for the agency in Pakistan.

"My recollection is, basically, it's a two-fold mission," Leader said. "There would be drug-related work specifically. But also, in light of the then-very-recent events on September 11, I think that he was going to go back to Pakistan with a view towards meeting with or gathering whatever information he could that might be useful to the US government regarding certain extremist elements there."

An excited Headley told friends and family that he was leaving on a mission. He explained that "the FBI and DEA had joined forces" and he would work for them in Pakistan, according to his close associate.

The DEA gives a far different account. The senior DEA official said Headley told his handlers he wanted to return to Pakistan for family reasons. The senior official said the DEA agreed to support ending his probation because of his past cooperation. The DEA provided a letter to the judge describing his work on drugs and counterterrorism, according to US officials and others familiar with the case.

The DEA then deactivated him as a law enforcement informant, a process that became official on March 27 of the next year, according to the senior DEA official. Headley was paid a total of $3,925 while an informant, the senior official said. DEA agents did not work with him again after the hearing, the senior official said.

The transcript of the Nov 16, 2001, hearing does not resolve the disputed versions. The prosecutor apparently did not know about Headley's extremism, unauthorised travel or the task force interview weeks before; he called him an "outstanding supervisee" with "no problems." The judge said probation was being ended "for the purposes of him returning" to Pakistan, and mentioned Headley's "continuing cooperation."

In the frenzied aftermath of Sept 11, US intelligence agencies were scrambling to recruit spies. With his language skills, Pakistani connections and undercover talents, Headley had potential. A US law enforcement official familiar with the case said he doubts the government ended the probation early just to reward Headley, and even let him leave the country, because he suddenly decided to stop being an informant.

"It's preposterous," the official said. "It defies any sort of logic at all. US attorneys are not in the business of granting presents for people. In the post-9/11 environment, there was a big push for intelligence assets."

A number of DEA informants moved to counterterror work during that period. Some were passed to the FBI or the Central Intelligence Agency, and a few were run jointly by the DEA with other agencies, according to former US law enforcement and intelligence officials.

In fact, a counterterror source said the DEA had discussions with the FBI and other agencies in late 2001 about which agency could best use Headley. The discussions cited his allusion to a relative in the ISI as a potential benefit, the counterterror source said.

During his testimony this year, Headley said nothing about deciding to end his service as an informant before going to Pakistan. Asked when he stopped working for the DEA, he testified: "The following year, in September. ... It was the time that I had signed up for."

The world of informants is hazy, according to law enforcement veterans. Agents at the DEA, FBI and other agencies sometimes use unofficial "hip-pocket" sources, the veteran officials said. Ex-informants sometimes surface and provide intelligence. Or they try to use past relationships with the government to justify their behaviour when they get in trouble.

Officials at other agencies say Headley remained a DEA operative in some capacity as late as 2005. The senior DEA official denied that, citing the agency's detailed records on informants. He said he had no information on whether Headley shifted to intelligence work for another agency but would not rule out that possibility.

The CIA and FBI deny that Headley worked for them. Today, nobody wants any part of him.

Chapter 4: The Path to Holy War

By February 2002, Headley was training in Lashkar's mountain camps. He did a three-week introductory course on ideology and jihad.

The US and Pakistan had outlawed Lashkar. But the ISI continued to fund, train and direct the group, which refrained from attacking Pakistan. The group's global networks and storefront offices in Pakistan made it easier to join than Al Qaeda. Lashkar camps churned out thousands of militants, some of whom went on to lead Al Qaeda plots in the West.

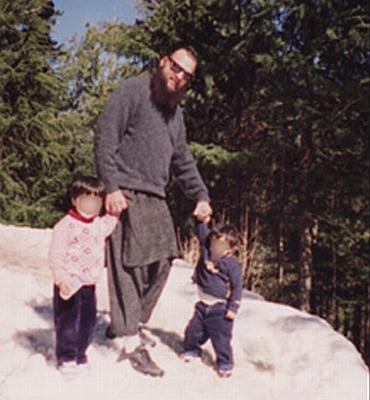

That summer, Headley returned to New York and proposed to his Canadian-born girlfriend with a diamond ring in Central Park. Photos show he had bulked up and grown a long beard. His sharp profile and receding, slicked-back hair gave him a hawk-like look.

In June, Headley visited his mother in Oxford, Pennsylvania, a small town about 50 miles from Philadelphia where she then ran a daycare center. She had become stout, favoured colorful dresses and wore her hair short and dyed blonde. She was a regular customer at the Morning Glories cafe and spent many afternoons talking to co-owner Phyllis Keith.

One day, Headley's mother said she was concerned because he was training in militant camps in Pakistan. She told Keith he was increasingly fanatical and had described meeting teenage trainees who had later died, according to US officials.

"It was kind of like mother to mother: 'I'm really worried about my son'," Keith recalled.

Keith had seen Headley once at the cafe. On a catering visit to his mother's home, she noticed his car parked behind the house as if he were hiding it. Keith called the FBI in Philadelphia and told them about the mother's account of Headley's involvement with militants in Pakistan. The conversation lasted about five minutes, she said.

Headley later told an associate that an FBI agent had gone to his mother's house and asked about him. But the FBI says there was no such visit. An agent in Philadelphia did basic record checks and closed the case, a law enforcement official said. The official did not know whether the agent was aware of the interview of Headley in New York the year before. Headley's links to the DEA probably caused the FBI to see him as less of a threat, officials say.

Headley did his second Lashkar training stint in August. When he was not at the camps, he lived with his Pakistani wife in Lahore. By then, two of their four children had been born.

On Dec 11, 2002, Headley returned to New York to marry his fiancee there. At the airport, border inspectors sent him to the secondary inspection area for questioning. It was not the first time. After his heroin smuggling arrest in 1988, border agencies placed him on a "drug lookout" list and stopped him at airports in 1993, 1996 and 2001 for questioning and luggage searches, according to US officials.

This time, however, inspectors were on alert for potentially suspicious travel patterns to Pakistan and other hubs of terrorism. They found nothing amiss. Headley was not on a watch list, and the inspectors did not know about the allegations by O'Donnell and Keith, according to US officials.

Days later, Headley married the Canadian woman at a resort in Jamaica. He did advanced Lashkar training in Pakistan in April, August and December. He wanted to fight in Kashmir, but the bosses had other ideas.

Headley was cultivated by Sajid Mir, a chief in charge of foreign recruits. Mir was about 30, a rising star. He was waging global jihad at a time when many Western authorities mistakenly saw Lashkar as a threat limited to India.

"My impression was that he was an authority and a power in his own right," said Charles Wardle, a former Lashkar operative from New Zealand. "He could pretty much do whatever he wanted."

Wardle, now 28, is one of Mir's few known recruits who is not dead or in prison. He was an angry drifter who arrived at Lashkar headquarters in the heady days of the fall of 2001. He hung out with American, French and British trainees whom Mir later deployed to procure equipment and scout targets in the United States and to carry out a bomb plot in Australia that was foiled in 2003.

The recruits included a Korean-American and a French-Caribbean convert: Mir was looking for operatives with unlikely profiles suited to espionage-style work.

Mir didn't let Wardle take paramilitary training because he had just converted to Islam. But Mir gave him travel cash and kept in touch as Wardle traveled to Saudi Arabia, where Lashkar militants helped him make his way to Iraq in time for the outbreak of the war.

Wardle narrowly survived combat alongside militants in the north.

In the summer of 2003, Mir sent Wardle from Pakistan to Dubai, a hub of Lashkar activity, for training in the use of explosives and espionage techniques. Mir visited him in Dubai.

Mir gave "the impression ... that I would be returning to my country," Wardle said. "I can only guess, but explosives training, I guess he would have had a target in mind."

Before training could begin, however, Dubai police arrested and deported Wardle in a roundup of Islamic extremists. Mir was also detained in Dubai at some point but used Lashkar connections to get out of it, according to investigative documents.

Mir did not seem fazed by the incident or, in 2007, by his conviction in absentia in France on terror charges. Pakistan did nothing in response to the verdict or an Interpol warrant from Judge Jean-Louis Bruguiere, who led the French investigation. Bruguiere is convinced that Mir was in the military or ISI.

"When you send an Interpol warrant and a country ignores it, it tends to confirm my theory that he was extremely powerful, that he was protected at high levels," Bruguiere said in an interview. "And the fact that no one has done anything about him, even today, confirms it once again."

Other investigators believe Mir was close to the security forces but not an officer.

"There are a lot of questions about Sajid Mir," Sageman said. "Is he really an ISI person who is within Lashkar-e-Tayiba? Or is he a Lashkar-e-Tayiba person who was trained by the military in the background? It doesn't matter because, in a sense, Lashkar-e-Tayiba was a proxy of the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate."

To be continued