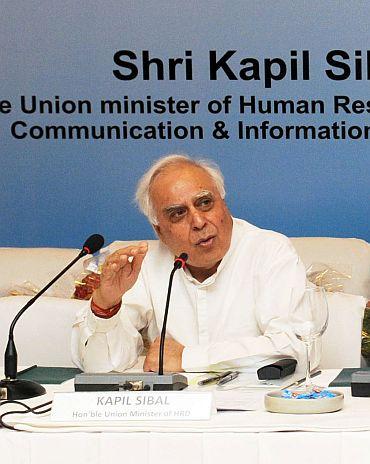

You cannot have an Executive outside the constitutional framework, answerable to nobody, because the chances of such an organisation corrupted by the sheer lust for power are much greater than the Executive functioning within a constitutional framework, writes Kapil Sibal, Union Cabinet Minister and a Member of the Joint Drafting Committee

The provisions of the Jan Lokpal Bill, proposed by Anna Hazare and his nominees must be analysed, keeping in mind the broad features of our constitutional structure.

Under our Constitution, the Executive is answerable to Parliament as well as to the Judiciary. To Parliament: when members from the Opposition seek explanations from the government for policy decisions, comment and analyse proposed government legislation and seek information from government.

Through robust parliamentary procedures, including debates, the people of India are informed of the manner in which the Executive functions.

The Legislature, namely the two Houses of Parliament, is answerable to the court which has the power, through judicial review, to strike down legislation on the touchstone of our Constitution.

Our legislators are also responsible and accountable to their constituents when they seek re-election after the dissolution of the House.

...

The judiciary, independent of both the Executive and the Legislature is accountable through an open and public judicial process. The hierarchy of courts helps correct judicial errors.

Individual judges are also accountable through the process of impeachment by the Legislature. That has thus far not worked very well. We need to ensure greater accountability of the judiciary by framing a law, which on the one hand protects judicial autonomy and independence, and at the same time ensures strict accountability.

In other words, each limb of the State -- the pillars of our constitutional system -- is accountable, one way or the other. That is the essence of our parliamentary democracy.

It is this essence, which is in danger, and is sought to be breached by the Jan Lokpal Bill proposed by Anna Hazare and his nominees.

The Lokpal, according to the proposed Bill, is an unelected executive body with independent investigation and prosecution agencies, answerable to none.

It is not answerable to the government, being outside it, since it will have the sole power to investigate all public servants. It is not answerable to the Legislature.

Outside government, we will have no access to its functioning, a prerequisite in informing Parliament.

Besides, it will have the power to investigate all members of Parliament. It is not answerable to the Judiciary except when it initiates the judicial process by taking recourse to the provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Besides, it will have the unique power to investigate members of the Judiciary.

Such an entity not accountable to any constitutional authority cannot be constitutionally justified.

One argument opposing the above proposition is that the same logic applies to the Judiciary because it too is not answerable to either the Executive or the Legislature.

This logic is erroneous for two reasons:

(1) All judicial proceedings are open to the public and judicial decisions are subject to revision, appeal and review. Judicial errors are liable to be corrected by superior courts. The Lokpal on the other hand is essentially an investigating agency.

(2) The independence of the Judiciary cannot be equated to the independence of an executive authority being the Lokpal, the prime function of which is to investigate and prosecute. The Judiciary seeks to protect citizens. The Lokpal seeks to prosecute them.

Autonomy of the Judiciary must be protected since the Judiciary resolves disputes. It is not mandated to prosecute people.

The second argument is that the Lokpal is just like the Election Commission and the Comptroller and Auditor General of India -- also independent constitutional authorities.

Again the comparison is odious. The Election Commission's functions are regulatory and periodic and the CAG's function is to analyse expenditure of government departments and agencies funded by the government to ensure that moneys allocated are not wastefully employed.

It is, therefore, clear that in the scheme of things, an unelected Lokpal who is not accountable, is anathema to our concept of parliamentary democracy.

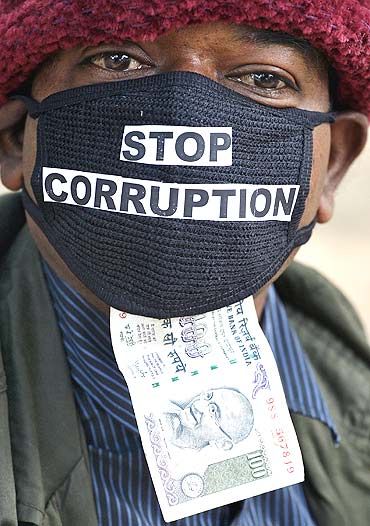

Another broad feature, which is worrisome, is the general premise underlying the Jan Lokpal Bill. It proceeds on the assumption that corruption has been institutionalised and is all pervasive; that there is confluence of interests in government departments when a subordinate public servant charged with corruption is protected by his superior since the fruits of corruption are shared by all.

Consequently, corrupt acts are not dealt with and if dealt with, are delayed. The same applies to the political process, as the political class is corrupt and seeks to protect itself by not enacting laws which make them accountable. These assumptions are not entirely accurate.

The premise is that if a Lokpal is set up outside the government, there would be no confluence of interests and the Lokpal will be able to cleanse the system. I find this premise inherently faulty.

Let us assume for a moment that we have put in place a Lokpal, which has within its ambit, all central government employees (about 4 million) and a Lokayukta in every state, which has in its ambit all state government employees (about 7-8 million).

If the Lokpal or Lokayuktas are to deal with corrupt acts of about 10-12 million people, what is required is a mammoth machinery both in terms of manpower and otherwise to deal with individual acts of corruption by government employees.

Where would that machinery come from?

Part of the human resource that is required will have to be transferred to the Lokpal from existing investigating agencies. The human resource in the CBI that deals with corruption under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 will have to be, to some extent, transferred along with personnel from other investigating agencies of government.