Photographs: Vaihayasi P Daniel/Rediff.com

Julia Lovell, author of The Opium War, explains China, past and present, to Vaihayasi P Daniel.

When Dr Julia Lovell, the British historian and author of The Opium War, checked into her hotel in south Mumbai on her first trip to India, she was startled to discover it had a bar named Opium Den.

Out of curiosity she ventured into the Opium Den and discovered a variety of authentic, carved, antique opium pipes decorating the wall of the pub. She inquired from a bartender if they were indeed opium pipes. But he said "No madam, they are flutes (!)."

Recalls Lovell, "In China, it's hard to over-estimate the nationalistic sensitivities that opium and the Opium War can provoke -- opium is the national poison, the national disease that turns China into the 'sick man of Asia' through the 19th and early 20th centuries. To come to Mumbai and find the name Opium Den being used over a chic bar generated a huge culture shock for me."

Lovell, a lecturer of modern Chinese history and literature at Birbeck College, University of London, was in India recently to promote The Opium War. She has won awards for her translations of the work of well-known Chinese writers into English (Eileen Chang, Han Shaogong, Zhu Wen, Lu Xun).

The Opium War is her third non-fiction book. She earlier wrote The Great Wall: China Against the World 1000 BC-AD 2000 and The Politics of Cultural Capital: China's Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature,

Her Opium... book tour has taken Lovell to all the geographical points that were once historically linked by the flourishing British-driven opium trade -- India, Hong Kong, Singapore and China.

British traders first started buying opium from India in the 1500s after they learned of India's wealth from accounts of the intrepid British explorer Ralph Fitch when he caught up with a fleet 'of one hundred and fourscore boates laden with Salt, Opium, Hinge (asafetida), Lead, Carpets and diverse other commodities' going 'downe the river jumna (Yamuna).'

Please ...

Mumbai's opium connection

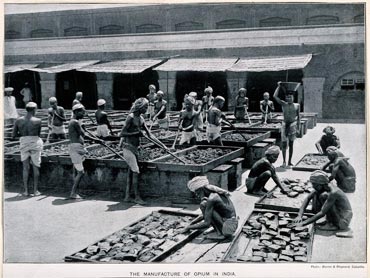

Chests of opium -- holding 60 odd kilos of carefully wrapped and packed opium each -- were auctioned in Calcutta and dispatched to China. Eventually, the British East India Company ran a booming multi-million pound opium exporting monopoly from India.

According to a report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: 'Despite a major opium epidemic in China at the end of the 19th century, there was little interest in suppressing a business that was so profitable for opium merchants, shippers, bankers, insurance agencies and governments Around 200 chests per year or 12.7 tons of opium entered China during this period.'

Our interview is conducted in a meeting room on the top floor of the Trident hotel in south Mumbai. It offers a splendid view of the city's rain-stained, crumbling colonial buildings that throng the docks.

Lovell is keen to point out the appropriateness of discussing the opium wars and trade against the backdrop of these once majestic buildings, many of which were built with opium wealth as more and more Malwa-origin opium was exported to China from Bombay.

The Bombay-based David Sassoon family -- after whom is named Mumbai's Sassoon Dock, the David Sassoon Library, all visible from the Trident -- profited richly from this trade, as did other Armenian, Parsi and Jewish Indian merchants.

Bombay's rise as a premier port and city in western India was linked to the export of opium to China. This trade eventually grew to 40,000 chests a year right from the docks visible from our window.

India, after stops in Hong Kong and Singapore, has offered a mixed bag of observations for Lovell. Indians are not as ambivalent about its links with the opium trade as folks in Hong Kong and Singapore were. Amitav Ghosh's two recent novels have ensured a fair amount awareness of the opium trade and India's role in it.

Lovell is quite surprised -- being a China expert in her first encounter with India -- to hear of India's uneasy view of China. Surprising too, she says, was India's lack of bitterness over the profits Britain reaped in India from opium.

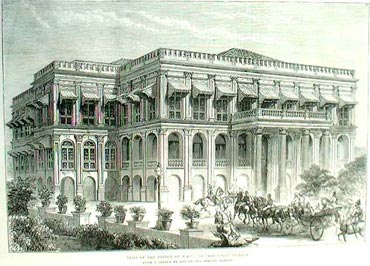

Image: This bungalow, once named Sans Souci (French for carefree), which now houses the Masina Hospital in Byculla, central Mumbai, was once the home of Bombay businessman David Sassoon, who made a fortune in the opium trade.

Please ...

'If the West criticises China, the Chinese government can press the Opium War button'

Image: Manufacture of opium in IndiaThe Opium War occupies a complex place in the Chinese consciousness. On the one hand, as my book shows, there is a significant diversity of 'non-official' views about the conflict.

On the other, the official view of the Opium War as the inaugural trauma of modern Chinese history remains politically very important because it represents a crucial source of political legitimacy to China's rulers it's the founding episode of Chinese nationalism.

The war is seen as the start of a Western conspiracy to destroy the country with drugs and gunboats. It begins China's 'century of humiliation' by the West, and China's battle to 'stand up' as a strong modern nation -- a battle that ends, inevitably, with the Communist triumph in 1949.

In China, this account of the Opium War -- chorused by history books, television documentaries, films and museums -- is far more than history: It has a powerful message for the present day.

In Chinese politics, the war (and the Century of Humiliation that it begins) stands for the long-term Western plot to undermine China.

If the West criticises China, the Chinese government can press what you might call the 'Opium War' button: It reminds the Chinese people that the West has always been full of schemes such as the Opium War, and is therefore not to be trusted.

To understand China's often troubled, touchy relationship with the West, you have to understand how and why China remembers events like the Opium War.

How different is that in India, in your estimation, considering India could/does have historical injustices to play up too?

I am afraid I don't know enough about how history is taught in India to comment on that question, although I am trying to find more out about it at the moment.

Certainly, both China and India are equally entitled to feel angry about the Opium War and about the opium trade -- in the case of India, the opium trade represents the systematic exploitation of India's natural wealth for the enrichment of the British empire.

And yet in China, these events are a national wound, while in India, they are (as I understand) remembered rather little. I am intrigued by this difference in public memory, and while in India I sought to understand it better.

Do you feel Chinese leaders are shrewder about pressing the opium panic button since they were able to use the Opium War Excuse as a way to sustain the legitimacy and relevance of a Communist government in China?

In China today, the Opium War still resonates strongly: It is the traumatic inauguration of the country's modern history -- the founding episode of Chinese nationalism.

It is seen as the start of a Western conspiracy to destroy the country with drugs and gunboats. It begins China's 'century of humiliation' by the West, and China's battle to 'stand up' as a strong modern nation a battle that ends, inevitably, with the Communist triumph in 1949.

This account of the Opium War is an important source of legitimacy for the country's rulers. The CCP (Chinese Communist Party) portrays itself as the only political force able to resist this plot.

To understand China's often troubled, touchy relationship with the West, you have to understand how and why China remembers events like the Opium War.

In terms of when this starts, it has been present in Chinese nation-State-building since the 1920s-1930s, but comes strongly back to the fore after the crisis of 1989 (both in China and in Europe), following which the Communist government actively portrays itself no longer as the champion of Marxist orthodoxy, but rather as the defender of the national interest (against the West), in order to bolster its own legitimacy.

Please ...

'China can seem more 'other', somehow more mysterious and opaque than other countries'

Image: Wealthy 19th century Chinese opium smokersI seem to notice this button being pressed when there is a significant international issue causing conflict between China and Western countries.

Conflict or disagreement can be usefully recast by China's State media as yet another attempt by Western governments to interfere with China's sovereign domestic affairs.

Why do stereotypes about China and its Opium War-related xenophobia persist in the West?

One reason, I think, is that China -- although it is more globalised now than at any time in its past -- can still seem very different to the West, and that makes non-specialists uneasy.

One reason for this perception is China's official Communist ideology; another is that linguistically China was never penetrated by Western languages in the way that India, South American or African countries were.

As a result, (rightly or wrongly) China can seem more 'other', somehow more mysterious and opaque than other countries and cultures that are equally geographically remote from Western Europe. And this sense of difference can generate unease.

Please ...

'China's concerns at the moment are very practical'

Image: British factories, Canton, part of the Thirteen Hongs, where foreigners were allowed to liveYou spoke about how through all your trips to China you had come to realise that China saw itself as a non-aggressor, non-imperialistic country. Therefore you expressed surprise that here in India there may be another view of China.

Yes; the idea that China has never in its history embarked upon a war of aggression or invasion against another sovereign country is fundamental to the contemporary political self-image of China's rulers, and to the theory of 'China's peaceful rise' developed over the past decade (the historical reality behind this question is another matter).

This idea is so enshrined in public life in China that I was intrigued to learn from our conversation that it does not seem to have been communicated effectively throughout India.

What were the interesting reactions you have received in India?

In the responses that I encountered, there seemed to be a combination of relaxation over the opium trade ("India is over it," one very poised, educated lady in her early 60s told me) but also embarrassment as indicated by the Parsi gentleman who asked me very earnestly if he felt that an apology to China about Indian merchants's involvement in the trade would be constructive in Sino-Indian relations.,/P>

Many people told me these events were forgotten, or at least neglected in public memory and India was more focused on more contemporary issues.

Is there a dichotomy in the fact that China, who suffered at the hands of British imperialism and became quite insular as a result, is perceived as quite imperialistic today by the rest of the world?

On your visits there and in chats with people do you feel the average Chinese understands these perceptions that the world has of their country?

My own personal feeling is that (at least up until my last visit to the country, last August), many Chinese people were very unwilling for their country to be considered imperialistic, in the sense of it becoming a superpower heir to the contemporary USA.

Although there is growing self-confidence in some quarters, in others there remains uncertainty. China remains such a mixed place in terms of incomes and development, that (until recently at least I am not sure about feelings in the absolute here-and-now) many ordinary people have long felt that China still has a lot of problems to deal with and cannot yet be considered a 'superpower.'

As to the consequences of imperialism for the 'national worldview' of a country like China (if indeed it is possible to generalise usefully about such a thing), on my recent trip around Hong Kong, Singapore and India, I was struck by the variety of responses that these places had to their historical encounters with British and other imperialisms.

India, for example, had a more thorough-going, longer-term encounter with British imperialism than China, and yet (my superficial observations tell me) seems to have responded to these events in strikingly different ways.

Similarly, in China you will find a great diversity of viewpoints on the impact of imperialism on China even if the public view remains relatively monotone.

Where is China headed?

Will it unintentionally mimic other present-day foreign powers or past powers in the role it assumes on the world stage in years to come?

I think many of China's concerns at the moment are very practical -- to do with economic, rather than ideological issues.

The quest to secure energy and materials to undergird its economic rise looms large.

article