Photographs: Reuters

Schaffer, director of the South Asia programme at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington, DC, think-tank, since 1998, has during her previous avatar as an American diplomat worked in New Delhi, Islamabad, Dhaka and Colombo.

She discussed the India-US relationship with rediff.com's Aziz Haniffa.

What prompted you to write this book?

I've been working on India for a long time, but in contrast to my years in the government when you were constantly bumping into the limitations of US-India relations, the whole situation changed dramatically with the end of the Cold War.

And so, the potential for the new relationship and the changed strategic situation, with India emerging as one of the countries that was going to shape Asia, and with Asia increasingly the focal point for US foreign policy, and my sense that while we have done an awful lot to build up the bilateral infrastructure of India-US relations, the regional and global dimensions were underdeveloped.

Also, I wanted to understand what could be done to take better advantage of the growing array of common interests between India and the United States.

Why do you call it 'Reinventing' Partnership?

The title has an interesting history. I was going to call it the Eagle and the Elephant, and then somebody published a book on Thailand with that title. I didn't want to have India confused with Thailand -- that somehow didn't seem right.

Reinventing Partnership was my idea, because it seems to me that we had talked a lot about partnership, but none of the existing models for partnership worked terribly well between India and the United States.

When the United States has had partners, they've generally been countries that started out as allies with a common view of security threats in the world. They've also been countries that were vastly less powerful than the United States, and while that's still true of India today, it may not be true forever.

India really doesn't have much experience in partnership, and the whole concept of non-alignment and the whole concept of strategic autonomy, which is still important in Indian foreign policy, make India a little bit suspicious of the whole idea.

So my contention is that in order to take full advantage of the ways that our interests run together, we need to reinvent what it means to be partners.

We need to find new ways of developing a close relationship, which neither side feels is a constraint and both sides feel is an opportunity.

Are you now convinced that the two countries can become partners in the real sense of the word?

I am basically an optimist -- and that is because I look at what India's major interests are, particularly in the region, but also in a more complicated way in the world; I look at what US interests are, and I see a growing number of interests that we have in common, and I believe that will keep pushing us together.

Where it will be complicated is that we don't really yet have the common habits of working together beyond the strictly bilateral agenda.

I think we have a good chance of developing that, but even if developing these habits takes a while, we are going to keep being pushed together by the fact that we are both interested in Indian Ocean security, we are both very interested in the integrity of the international oil markets, we both have a great deal riding on our international economic profile.

For India, its economic performance has become one of the features of national power in ways that it never was in the earlier years.

We both have a common interest in Asian security -- neither of us wants to treat China as an enemy.

Both of us want to engage with China, both of us have in the longer term, strategic challenges that China represents. So, with all of these things in common, we are going to keep being pushed together.

Isn't your argument that the bilateral relationship is now rock solid from the regional and global point of view taking too much for granted?

The relationship is much stronger than it was, but it still needs work -- and most importantly, the things that still need work include some of the things that from India's point of view are the entry point to a larger regional and global agenda.

I am thinking in particular of defence trade, defence high technology and the aspects of the nuclear deal that are not yet fully in place.

It is not that the larger global agenda depends on those substantively, but these have been the ways that the United States and India have shown one another that we really have changed in the way we deal with one another, and that's what is the entry point for working on pieces of a larger regional and global agenda.

What I have in the book is an argument about what is working now, what could be working better and most importantly, how we can nurture it. I've also got some discussion in the final chapter of what they call wild cards -- in other words, things that could happen that might change the dynamics I've described.

'The nuclear deal was larger than life'

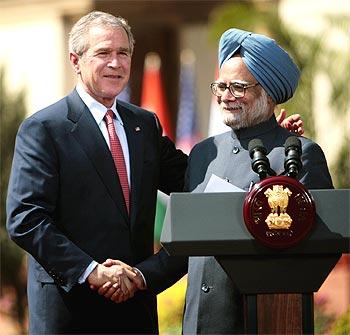

Image: Then US president George W Bush with Prime MinisteManmohan Singh, the key architects of the n-deal.Photographs: Reuters

First of all, let me back up for a second. The partnership, as it exists today, has been built by both major parties in both countries. That's really important. It has not been a political party issue in either place, except to a limited extent with the Left in India.

It hasn't been a political party issue with any of the parties that have a reasonable aspiration to dominate the government, to lead the government in India.

The nuclear deal was larger than life for both its substance and its symbolism, because it was an effort to quite dramatically change policy in an area where the United States had basically put India off limits -- not just the United States, but the bulk of the international community.

I am not at all surprised that it has turned out to be controversial in both countries, and I expect that it will continue to be the case.

From the US point of view, we are trying to do two things at the same time --- on the one hand, to open up civilian nuclear cooperation with India, and, on the other hand, to persuade both our domestic audience and our international friends that we are not giving up on nonproliferation. It turns out to be difficult to do both of those things at the same time.

In India, on one hand you have a great desire for civilian nuclear cooperation, for eligibility to buy nuclear stuff overseas, and on the other hand, you have constituencies -- leave aside the political Left, I am really thinking of the nuclear constituency -- that are sceptical of whether the United States will actually come through.

So the US will have to jump over a really big hurdle.

As a result, every agreement on this nuclear deal has been a really tough negotiating challenge and I have to tell you, I am astonished that the United States actually agreed to what was in the 123 Agreement -- but they did agree, and the Obama administration speaking through no less a person than Hillary Clinton has confirmed that they are committed to implementing that.

So, I expect that we are going to continue working on the implementation, and that we are going to have trouble every step of the way. But I don't think that every bit of implementation has to be finished before anything else can happen.

I hope that we have a level of maturity on both sides where we can recognise that these are difficult issues that are both politically and technically complicated, and that we therefore have to plug away seriously and in good faith -- but the rest of the world doesn't stop while we are doing that.

Obama and Clinton have in recent statements committed the US to implementing the nuclear deal -- but there has also been an infusion of non-proliferationists like Ellen Tauscher at the US State Department, Gary Samore at the US National Security Council, and Robert Einhorn as senior adviser to Clinton. Also, Obama and Clinton made clear the administration's commitment to the CTBT (Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty) and the FMCT (Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty).

Won't the administration's push on these issues going to be a source of friction between India and the US even as the nuclear deal continues to be implemented?

The CTBT is something that this administration wants to do. They have wisely decided that they are going to start by trying to get it ratified in the United States. Ratification requires two-thirds, and the Democrats have 60 in the Senate. They need seven more so this is not a done deal.

Assume it does get ratified at that point, I am assuming that the United States will urge India to join the CTBT. But it will be a different India from the one that refused to associate itself with the CTBT, and I think, India will just have to look at its interests at that time.

For one thing, having the nuclear agreement in place with the United States puts the whole India-US part of it in somewhat different light. So, the CTBT is one aspect, but only one.

As for the FMCT, the Indian government committed itself to participate in negotiations. It did not like the Bush administration's approach to this issue. It is likely to find the Obama administration's approach much more congenial, particularly on the issue of verification.

I appreciate that this is a subject that probably makes a lot of the Indian government officials nervous, but we'll have to see what happens.

But there is a bigger challenge, and that is what the non-proliferation system is going to look like. I have argued in the book that we have an opportunity to try to make the nonproliferation system more inclusive, to set up a structure or structures in which India can be a full participant rather than the object of control.

And I hope that the administration will devote some of its energies to trying to do this. I have spoken to some of the people in the administration, and this is an idea that they are mulling over.

It hasn't really taken policy form yet. But that's where I see the possibility of India and the United States actually finding a way forward on nonproliferation that isn't simply a tug-of-war.

In your husband Howard Schaffer's book Kashmir and the Limits of Influence of the US, he recommends that the US support India's bid for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. Are you in agreement that this would be part of a reinvented partnership?

India and the US still have a lot of trouble working together in multilateral forums. We've had a bad relationship on multilateral trade issues. Minister for Commerce Anand Sharma was in the US recently and he's clearly trying to start working from a somewhat new position, but he still has a position to protect, which is India's concern for its farmers.

So the big question in my mind on trade is, does India believe that it has something to gain from a successful Doha Round, and something to lose if the Doha Round is unsuccessful?

If India's calculation on that has changed, then India and the US will figure out how to deal with each other, because that's been the primary obstacle.

I've got a whole chapter about the multilateral arena. Basically, what I am arguing for is for a much more encouraging US posture towards India becoming, as one of my Indian friends put it, a member of the board of the world.

The best example where that's actually working now is the G-20 and the discussions on financial sector reform smaller discreet meetings that take place out of the glare of public opinion.

As far as the UN Security Council is concerned, my view is that India isn't going to achieve a permanent seat on the Security Council for some time. In the short-term, the US is not keen to see the Council expand, even though we claim to support Japan.

Russia probably supports India. Britain and France are probably more concerned about making sure that their seats don't get diluted.

China, whatever else it says, is going to oppose India's bid for a permanent seat look at what they did at the Nuclear Suppliers Group.

So, regardless of what the US does, India's chances of getting over that hurdle in the short-term are very poor. India is probably going to be on the Security Council in another two years, however, in a non-permanent seat.

I think this will probably be pretty uncomfortable for the Government of India because every time the Security Council votes, India will have to choose whom it's going to irritate -- because any vote will irritate someone.

So this will be an interesting test drive for India, trying to figure out how it manages its patterns of friendships -- the fact that there are other developing countries that have certain expectations of what India does in the UN and its emergence as a global power.

I believe that in the shorter term, what the US ought to be pushing for is greater Indian participation in the G-20, in APEC, greater inclusion in the groups where important decisions are made or important recommendations are shaped for the world.

I would look towards the time when the Security Council would be a realistic goal, but that's going to require some changes among the Permanent Five as well.

'India is going to continue focusing on the terrorism issue'

Image: Mumbai's Taj Mahal hotel ablaze during the terror attacks last November.Photographs: Uttam Ghosh

I believe that in many ways, Pakistan is a kind of an albatross around India's neck in the sense that the unresolved problems with Pakistan are a bit of a drag on its other international ambitions.

The fact that the US is deeply engaged in Afghanistan, and is at this point trying to work with Pakistan so that it becomes part of the solution rather than part of the problem, adds to this. It's not a major impediment to US-India relations, but it's there.

The way the recent elections came out in India gives the Indian government as much flexibility as it could possibly have hoped for. Pakistan was really not an election issue because no one disagreed. After Mumbai, everyone was taking a fairly hard line.

Manmohan Singh said he wants to restart the peace process, that he wants to extend a hand to Pakistan. But he has also said that his first priority is preventing Pakistani territory to be used against India. So he's put that marker down, and that is likely to dominate the first few Indian-Pakistan contacts.

I hope though that he really is serious about trying to get back to the peace dialogue that was taking place before. I am not naive -- obviously the terrorism potential is a major preoccupation for India, and it should be.

But what the back-channel talks of the special envoys of (then Pakistan president Pervez) Musharraf and of Manmohan Singh had accomplished during the Musharraf years was a considerable narrowing of the gap between India and Pakistan on the most painful issue, which is unfortunately Kashmir.

If that process can be resumed and if the governments in India and Pakistan are strong enough to start doing the political homework that goes into making that a reality, then you have a chance of actually being able to move beyond that.

Now, before the elections, I would have argued that the governments in both Pakistan and India were really not in a position to do that. Today, I would say, the Indian government might be, but only if the Pakistan government can get there, which they are not at this point.

So, at this point, they are not ripe for a breakthrough.

What would be most useful for them to do, it seems to me as an outside observer, is to continue doing the discreet homework of figuring out what need to be the ingredients in a settlement, against the day when you will have governments in both countries that have enough strength to move ahead.

But isn't this all wishful thinking -- any movement on the Kashmir issue -- because India has strongly asserted that the pause button on the composite dialogue is not going to be lifted unless Pakistan moves credibly and deliberately against terrorism from its territory against India and brings those who perpetrated the Mumbai terror attacks to book?

It is interesting to me how this discussion has developed. Immediately after the attacks in Mumbai, you had this very inconsistent response on the part of the Pakistanis, where on the one hand, there was sympathy and condolences, and on the other hand there was questioning whether Kasab really existed or whether he was Pakistani until eventually, they got off that.

You are going to see a similar zig-zag path on Kashmir, because this is a domestic issue of some consequence in Pakistan.

India obviously is going to continue focusing on the terrorism issue and that's a necessary part of the process, but I certainly hope that they get to the point where they can add other issues.

'India, US face uncertain future in Iran'

Image: Iranian President Ahmadinejad will 'be governing a changed country'Photographs: Reuters

But after the recent post-election violence in Iran coupled with Washington's paranoia over Iran's nuclear programme, won't Delhi's relations with Teheran be an area that could impact adversely on this partnership that you are so optimistic about?

I actually don't see India playing much of a role in bringing the United States and Iran together. In principle it could, but I don't think that's something India is interested in doing.

India has its own strategic interests in Iran, in terms of land access to Afghanistan, in oil and gas supplies although the availability of oil and gas from Iran could be more of a problem.

India and the US have already had stark differences on this, if you think of the US attitude towards the proposed Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline as a case in point. What's happening in Iran now, however, may really change the landscape for both India and the United States.

Even if the ayatollah's word holds and (Mahmoud) Ahmadinejad carries on as president, I think he will be governing a changed country.

And as far as I am concerned, both India and the US face a much more uncertain future in Iran. I would guess that any government in Iran will want to continue the nuclear programme, so the US will continue to have that problem.

It could be that you would see a government that might pull back from Iran's role in terrorism, which had been the original killer issue between the United States and Iran.

But you are also likely to see an Iran that's very internally focused, and that could make a difference in how India looks at Iran. I believe that this is a great example of the kind of issue where Indians and Americans should be quietly comparing notes, because we can learn some things from each other.

article