Why is it that the public face of Islam is today associated largely with the dry and literalist Wahhabi and Deobandi versions? Why does the Sufi way of Islam appear to have given way before them?

It all began with the discovery of oil in Arabia, which has really proven to be a curse for Muslims. With its massive oil revenues, the Saudi State has sought to export its Wahhabi version of what it calls Islam to Muslims all over the world as an instrument to bolster the legitimacy of the Saudi regime, which lacks popularity in its own country. This literalist, stern, authoritarian and radical and warped version of Islam has been liberally funded, through setting up mosques, publishing houses and other institutions, among Muslim communities across the world, including India.

In India and other Asian countries, Wahhabism has gained a big boost from workers in the Gulf many of who, during their stay there, have converted to that ideology. All this has resulted in a growing attack on local Muslim cultures and Sufi traditions, which the Wahhabis regard as un-Islamic. In many countries, Saudi embassies also act as centres to promote or outsource Wahhabism, funding local Wahhabi institutions, publications and propagandists.

So, this is why the Wahhabi version of Islam appears so publicly visible today. Yet, it is crucial to note that the silent majority of Muslims are not Wahhabi at all. Most Muslims are still associated with Sufi traditions in some way or the other, which I regard as authentic Islam. Even in Saudi Arabia itself, the Wahhabis have not been able to stamp out Sufism, particularly in the more cultured Hijaz area, in contrast to the Najd, which is where the Wahhabis originate from.

The Wahhabis prohibit other Muslims from praying the way they want to in Mecca and Medina. In these two cities, they have destroyed numerous monuments associated with the Prophet, his family and his companions, as if they are the owners of these places. They want to destroy the whole 1400 year-old Muslim tradition itself. The whole trajectory of Wahhabism is rooted in hatred and violence. The alliance between the mullahs of the Wahhabi Al-e Shaikh and the rulers of Saudi Arabia, the Al-e Saud, is like the oppressive nexus between the Christian Church and the monarchy in medieval Europe. It is proving to be a curse for Muslims.

But if, as you say, most Muslims are not Wahhabis, or are in fact opposed to Wahhabism, how has Wahhabism managed to get such support? Why have Muslims associated with Sufi forms of Islam not spoken out or opposed the Wahhabis?

This has, in part, to do with the fact that, unlike the Wahhabis, the followers of Sufism are not well-organised. They don't have massive funds at their disposal, unlike the Wahhabis. In contrast to the latter, they are not combative. They don't go out and preach and demand that other Muslims accept their way of understanding Islam, which is what the Wahhabis do. They are moderates, and believe in moderation, not in aggressively converting others to their way of thinking. They don't brand other Muslims as apostates and condemn them as wrong. They just let you be the way you are. This is because they believe that it is for God to guide people if He wills.

Another reason why the Sufis are not so publicly visible today is because the Sufi khanqahs or hospices, which were for centuries centres of instruction and spiritual training, have largely disappeared. All that remains now are dargahs or Sufi shrines that today largely function as centres of mediation, where people go in the hope of having their requests met from God through the agency of the buried saints.

No, not at all. Sufism is authentic Islam, and Islam is a religion of victory. Our Prophet was victorious. Islam offers hope, hope for victory in the end despite all odds. If we lose hope, we lose faith. As the saying goes, loss of hope leads to infidelity. The Prophet explained this maxim beautifully when he said that if one has a sapling in one's hand and the day of judgement is just about to arrive, one must still plant it. That is the spirit of hope in the face of trials that Islam talks about. As a Muslim, I believe that trials come from God. Wahhabism is one such trial but, in the end, I know we shall triumph over it.

Today, especially in the West, there is an enormous interest in Sufism. There are new Sufi masters who are attracting vast numbers of seekers. Many of them have a strong presence on the Internet and so have a global audience. Unfortunately, the media does not highlight this fact, and also the fact that the vast majority of Muslims are not radical Wahhabis. Just because they are loud, aggressive and violent, the media tends to focus on these radicals as spokesmen of Islam, which gives both Islam and Muslims a bad name.

But isn't it a fact that popular Sufism is itself seen by growing numbers of Muslims as superstitious and corrupt? Many custodians of the shrines of the Sufis are known to make a living out of pilgrims.

What you say is true, but then corruption is today endemic in every sphere of society. There are, needless to say, scores of fake Sufis, but this does not mean that real Sufis do not exist. About the allegation that popular Sufism is rife with un-Islamic superstitions and practices, there is some truth in this argument, but many practices that the detractors of Sufism brand as un-Islamic are actually, to the Sufis, beneficial innovations or biddat-e hasana. These cannot be dismissed, as the Wahhabis so easily do, as 'un-Islamic' and as 'wrongful innovations' (biddat-e sayah).

The Wahhabis have a very narrow and literalist understanding of biddat, condemning 1400 years of Muslim scholarship, spiritualism, culture, poetry, philosophy, and art as 'un-Islamic'. They go so far as to brand the great Sufis, who were flowers in the garden of Islam, as heretics. They want to impose an Arabised culture, based on tribal Bedouin traditions, in the name of Islam and to totally destroy the beauty of Muslim civilisation, branding all this as biddat and, therefore, as un-Islamic. For them, the soul-stirring, God-inspired verses of Rumi or Sadi are undistilled heresy. As far as I am concerned, I regard Wahhabism as a heresy and as nothing to do with Islam at all.

Historically, Islam has been able to spread outside the Arab world because it accommodated itself to local cultural milieus. With what you call their extremely narrow understanding of biddat and their stern opposition to Ajami or non-Arab cultural traditions, what implications does Wahhabism have for the universal appeal of Islam?

In contrast to how the Wahhabis perceive it, Islam is all about cultural diversity. It is like a river that flows and whose tributaries rush to join during the course of its travels. It is an undeniable fact that the world of Ajam -- the non-Arab Muslim world -- has played a much more important role in the development of Muslim culture and philosophy than the Arab Bedouins.

One of the reasons for the vibrancy of Islam historically has been its capacity to express itself in multiple local cultural forms and milieus and to find God therein, for the light of God, as the Sufis say, is present in every particle of His creation. So, Muslims in India expressed their devotion to and search for God in soul-stirring qawwalis, and African Muslims did the same by playing drums and singing hymns. For their part, the Wahhabis condemn all this as biddat, as un-Islamic, thereby seeking to seriously limit the universal appeal of Islam and its ability to adjust to different cultural contexts. This goes completely against the 1400 year-old tradition of Islam.

Sufis also appreciate the fact of religious pluralism as the will of God, which is why they had such a powerful appeal even for many non-Muslims. This is also why it was the Sufis who were the principal agency for the spread of Islam. In contrast, the dry, literalist, Arabised version of Islam that Wahhabism represents is wholly hostile to pluralism, to people of other faiths, whom it exhorts upon Muslims to demean, to war against and to subjugate. Naturally, Wahhabism, in complete contrast to Sufism, can hold no appeal whatsoever to non-Muslims, and can only lead them even further away from Islam.

Image: Kashmiri Muslims pray at the shrine of Sufi saint Sheikh Dawood on his death anniversary in Srinagar on May 9, 2010. Hundreds of Kashmiris who believe in Sufism thronged the shrine to observe the 361st death anniversary of Saint Dawood, who preached Islam to the region over 300 years ago

There is a saying of the Prophet that God is Beauty and likes what is beautiful. Throughout the centuries, Islamic scholars have warned people not to engage beyond the required limits with legal issues because it might blind them to the other, spiritual aspects of Islam. In contrast to this, the Islam of the legalists is dry, inflexible and devoid of beauty, love and compassion. It is concerned only with the law and punishment. This is a reflection of the culture of the illiterate desert Bedouins, the backbone of Wahhabism when it emerged, who had no literary tradition, and who were obsessed with the external (zahir) dimensions while neglecting completely the inner or esoteric (batin) dimensions of the faith.

I think it has now become crucial for us to highlight alternative narratives of Islam in order to challenge the monopolistic claims of the Wahhabis and other such groups.

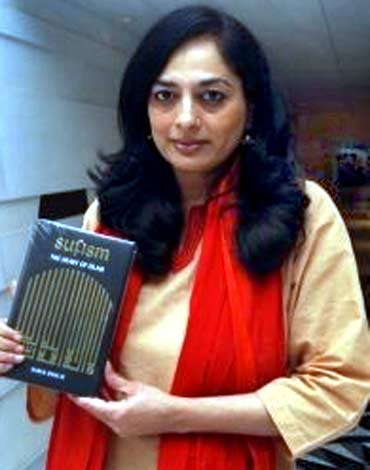

Highlighting what you call alternative narratives of Islam is what you are trying to do with your regular appearances on various TV channels as well as your recently-published and widely acclaimed book, Sufism: The Heart of Islam. As someone who is not a madrasa-trained scholar, and a woman at that, how do the ulema react to you speaking about and interpreting about Islam? Are you accused of attempting a task which, they might argue, you are not qualified for?

I must say that the Indian Muslim ulema whom I have interacted with -- and these include Deobandis and Ahl-e Hadith maulvis, whose aqidah or religious beliefs I do not share, have, on the whole, treated me with considerable respect. They know that I, too, respect them, and that I come from a point of view of faith. I do condemn the Wahhabi ideology, but I never speak against the Deobandi or Ahl-e Hadith ulema, the latter being even closer to classical Wahhabism than the former.

I believe in the principle that your faith is yours and mine is mine, as articulated in the Quran. There can be no compulsion in religion, for God guides whom he will. They realise that I am able to talk about Islam and articulate Muslim concerns and views in the media, and they respect me for this. I have never used terms such as 'mullah Islam', which some ultra-secularist Muslims do in order to dismiss the ulema altogether, treating them as their foes.

We must refrain from stereotyping the ulema in this manner, and of approaching them from a position of arrogance or antagonism. After all, Muslims need the ulema who have spent many years of their precious lives studying the Quran and the Hadith, teaching it to Muslims, and carrying on with the tradition of Muslim learning. I cannot do without the ulema myself. A maulvi sahib comes regularly to my house to teach my son to read the Quran. When I die, I hope a maulvi sahib will come to pray for the salvation of my soul.

In this regard, I would also like to say that it is completely baseless to claim, as some do, that the Indian ulema are creating terror or training terrorists in their madrasas. There is no truth in this allegation. It is true that I, like many other Muslims, might differ from them on certain views and beliefs, but we must understand that we all are victims of our own circumstances and that we all have a concern for the community at heart. All of us, including myself, have our own limitations, and the ulema are no exception to this rule. They, like the rest of us, may be limited in their understanding of various issues, but I have always held them in respect.

We must also acknowledge the positive things that some of them are doing. For instance, I am not a Deobandi, but I certainly welcome the much-needed fatwa issued by the Deoband madrasa condemning all forms of terrorism, including in the name of Islam, as un-Islamic.

My point, therefore, is that we should seek to engage with the ulema instead of shunning them. This task is crucial if efforts to articulate alternative narratives of Islam are to succeed and gain general acceptance among Muslims. We need to learn much from the ulema at the same time as we need to sensitise them to the changed demands and conditions of today, to the needs of the community, to the need to creatively and positively interact with the media. We have to look at ourselves and at the ulema as co-seekers, who might both have something to learn from each other. We have to think of how we can evolve a common minimum programme along with them, despite the fact that we may not agree with their views and beliefs on a range of issues.

Image: Students sit around their teacher on the floor during a traditional Sufi "halaqa" (study group) at the Ribat Tarim religious school in the historical city of Tarim in southeastern Yemen February 23, 2010. Tarim has long been a teaching centre for Sufism, a mystical strand in Islam

By this I mean the need to articulate the legacy of 1400 years of classical Islam, or Sufism, what is called 'tazkiya' or purification of the self. It is a discipline that which the literalists want to wipe out. It is the Islam of the silent majority of Muslims, even today. It is an Islam of moderation. I am happy to call myself a 'moderate Muslim', even if that label sounds jarring to some ears. After all, according to Islam the ummah of Muslims is the ummatan wasatan or the 'moderate community', the 'community of the middle path'.

Islam teaches us to be moderate in everything: in what we eat, what we earn, what we spend, how much to pray, how we relate to people of other faiths, and so on. Extremism and extremists, therefore, have no place in Islam. It is a fact that the vast majority of Muslims are moderates, and extremists like the Wahhabis are only a fringe, though loud and aggressive, minority.

So, articulating alternative narratives of Islam means to articulate this vision of the moderate Muslim majority. I think for this task to really take off, it is important for middle-class, modern-educated Muslims to also be engaged in it, and not to leave the task of studying, interpreting and articulating Islam simply to the traditional, conservative ulema. But at the same time, this should not be a mere academic exercise. Those engaged in promoting these alternative discourses of Islam must also live these discourses in their own lives.

If, as you say, the moderates are really the majority among Muslims, why does the media tend to depict the radical fringe minority as representing Islam and Muslims?

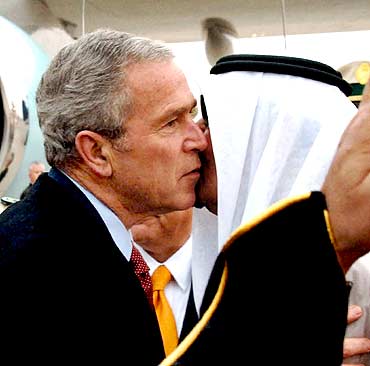

I have already dealt with this question, but let me add that this media projection of the radical obscurantists as spokesmen of Islam also has to do with globalisation and the globalised media. The image of Islam as synonymous with Wahhabi hate and radicalism was aggressively promoted by George Bush, when he was the American president, and by the largely Jewish-controlled American media.

The Saudi regime, despite Wahhabism's abhorrence for non-Muslims, is thoroughly pro-America and depends on America for its survival. So there has been this nexus between the American establishment, the Jewish-controlled media and the Saudi Wahhabi state. The American media aggressively sought to project the image of Islam and Muslims as the new enemy, an enemy driven by hatred and violence. Given its global reach, it succeeded in influencing global opinion. Following its lead, large sections of the Indian media, too, began toeing its line on Islam and Muslims.

There is also the factor to consider that radicals provide the media with the sound-bytes that it craves for. They actually cater to the media and so the media highlights them. They trigger off debates that the media laps up but which embarrass Muslims and give them a bad image. That is why the silent, moderate Muslim majority is almost completely invisibilised in the media.

That said, one cannot absolve Muslims of their responsibility in this regard. We can't keep blaming others, including the media, for our predicament. There is an almost total lack of creative intellectual discourse among Muslims, at least in India, which has allowed the Wahhabis and other obscurantists to claim to speak for them and for Islam as well. Muslims are not good communicators any more. We have failed to exemplify, in our own lives, the true message and values of Islam, the values that the Sufi saints, for instance, exemplified. I mean, if you go about blowing up buses and then claim Islam is a religion of peace, you cannot seriously expect anyone to believe you.

Muslims have to learn to introspect. I am sad that not enough of this is happening. We cannot, as I just said, keep blaming others for our problems, for our bad image in the media. We have to see where we have gone wrong, to examine what is wrong with our discourse, with our way of understanding our faith.

That said, I think we also need to understand that Muslims across the world do have genuine complaints. They suffer from a general sense of humiliation, of being despised, of suffering at the hands of others, as in Palestine and Iraq, and of living under brutal dictators in Muslim lands who have no popular legitimacy but who survive simply because of American backing.

Image; Former US President George W Bush with Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah bin Abd al-Aziz Al Saud at King Khalid International Airport in Riyadh on January 14, 2008

I make a total distinction between the ulema, on the one hand, and people like Zakir Naik, on the other. Zakir Naik is no alim. Even the ulema would refuse to consider him as such. No ulema in India regard him as an authoritative teacher.

I have great problems with the Wahhabi ideology that Zakir Naik and his television station are propagating. He is totally against Sufism, for one thing. His selling point is his memory, his ability to quote line and verse from the Quran, the Bible, the Gita and so on, and this is what mesmerises his viewers. I think the ideology that he is propagating is very dangerous, and could lead to radical, confrontationist and extremist tendencies. I also detest the way he runs down other religions, which causes his audience to exult and clap.

This is not the Islamic approach to deal with other faiths and their adherents. The Prophet and the Sufis never did anything of this sort. They related to others with love and compassion.

Nor is his the sunnat or Prophetic way of interacting with non-Muslims. The Prophet welcomed a group of Christians to the mosque in Medina and allowed them to pray, in their own way, therein. The Christians did not accept Islam and left, but the Prophet never harangued them or threatened them that they would go to hell for this. He simply offered the Christians the message of Islam, and left it to them to accept or not, without condemning them, for he knew that it was for God to guide them if He willed.

The contrast with Zakir Naik is really stark in this regard. I am appalled that his followers treat his programmes more like an achievement show. An assembly of the righteous should bring forth tears from the eyes and the heart, not applause. The Quran is not something you hear and clap. You should be moved to weep at its recitation.

What do you think could be done to improve media images about Islam and Muslims?

I think, as I said earlier, articulating alternative narratives about Islam, rooted in compassion, love and mercy, is really crucial in this regard. And these narratives should be articulated through the media.

But, let me say that there are also serious limits to what Muslim organisations can do in this regard. Creating a media image of a religion or a community is not something that can be stage-managed. You have to exemplify that image in our own life, you have to believe in it and, in fact, you have to be that changed image yourself. The Quran sets the highest ideals possible in a society. Muslims have to exemplify the message of the Quran in their daily lives to bring about a change in people's perceptions of Islam.

Simply talking about it in the media is not going to change others' perceptions of you if you do not live by those values yourself. You cannot pretend to be what you are not. You cannot pretend to be the media image that you want projected if you do not yourself embody and exemplify that image, as a person, as a community, because, sooner or later, your claim will be exposed. Islam teaches that compassion is one of the attributes of God, and unless you have compassion and relate to others compassionately, no amount of insisting on the media that Islam is a religion of compassion will convince people of your claims.

As Islam teaches, all that is not true will, ultimately, perish and only what is true shall remain. So, my point is that to change media images of Muslims we Muslims have to be true to the authentic values of Islam -- love, mercy, compassion and so on -- and to embody them in our own lives. If this is absent, no amount of preaching or protest or media networking will make any difference to others' perceptions about Islam and Muslims.