The public prefers thrillers that carry the threat of knocking down governments, derailing election campaigns and seeing ministers and officials go to jail, says Sunil Sethi.

Out, damn'd spot! out, I say!" cries Lady Macbeth as she stumbles about in her sleep but, as her co-conspirator knows, not all the ocean can wash off the stains. Like Banquo's ghost, there are some murky stories that won't go away.

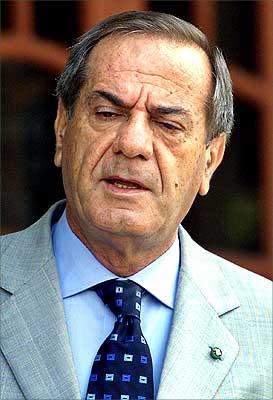

The Bofors gun deal is a classic political scandal that is back, a quarter of a century later, raising questions that were never answered in the first place: was Rajiv Gandhi bribed or was he in the know? Why was the Italian middleman Ottavio Quattrocchi allowed to get away? Was Amitabh Bachchan deliberately dragged into the controversy?

At a reported Rs 64 crore in pay-offs, the takings seem piffling today compared to the big bucks associated with 2G, the Commonwealth Games and a host of other scams. Why some corruption and sex scandals manage to stick around while others fade away may tell us something about the limits of public forgetfulness and the shifting standards of morality.

Who, for instance, can now recall details of the Telgi stamp paper racket, the spurious rice exports to Ghana and innumerable defence deals? Why was Monica Bedi on the run with Abu Salem, or her namesake Kiran Bedi, the guardian of public morals, fudging travel expenses? Will Abhishek Manu Singhvi's romp be remembered once his chamber is redecorated? These are scandals past their sell-by date.

...

The public likes its best bites to be tasty. It prefers thrillers that carry the threat of knocking down governments, derailing election campaigns and seeing ministers and officials go to jail. It is gripped by stories that carry a whiff of glamour, foreign locations and suspenseful drama.

Bofors contains many of these essential elements, from Rajiv Gandhi's election loss in 1989 to Amitabh Bachchan's "lost years" to a shadowy Italian businessman getting off scot-free to find a safe haven in Argentina. Lalit Modi's current sanctuary in London and obdurate refusal to return is not the same thing. Quattrocchi was accused of snaffling public money, Modi of defrauding private funds. Bofors has the additional cachet of a mystery that may never be solved, like the sinking of the Titanic.

Being traditionalists, Indians tend to be prim and pretentious about sex scandals. It was the British humorist George Mikes who once observed that whereas the Continentals had sex lives, the British had hot-water bottles. We are a nation of hot-water bottlewallahs — prudish rather than prurient.

...

Numerous prime ministers, ministers and public figures have mistresses, short-term girlfriends or live in stable extra- or non-marital relationships. We know about them, but don't publicise them. In the land of the Kama Sutra, such peccadilloes are generously overlooked — except where the suggestion of sex is linked to heinous crime. The murders of Jessica Lal, Bhanwari Devi and Aarushi Talwar are unforgettable, but who cares about starlets in sex CDs, legislators watching porn in the Karnataka assembly or Niira Radia's sexy dress? They provoke derision rather than outrage.

Notoriety is a key component of scandals that possess a long shelf life. Small-scale graft, land mafias in full-blown action and rape on the streets are steadily on the rise, but they are so commonplace that, in the collective consciousness, hardly considered scandalous anymore. High living, luxury imports and those with aspirations to folie de grandeur used to provoke opprobrium and outrage. Captain Satish Sharma importing Italian tiles for his swimming pool constituted a big scandal in the late 1980s, but Sheetal Mafatlal walking through Mumbai customs with an overload of unaccounted gold and jewellery a couple of years ago was considered entertainment.

Unbridled ostentation is now par for the course, gilt-edged but guilt-free. The arrival of post-modern architectural monuments such as "Antilla" in Mumbai or Mayawati's blitz of statues invite awe and envy, rather than shock and horror, as the indulgences of a new class of the ultra-rich and powerful. In the school for scandal, there are new lessons taught and learnt every day.

...