Photographs: Reuters Ajai Shukla New Delhi

Last week's unceremonious dismissal by US President Barack Obama of his military commander in Afghanistan, Lt Gen Stanley McChrystal, should be carefully studied in this country.

In contrast to India, where civil-military relations remain mired in wary mutual watchfulness, America has demonstrated a robust civil-military structure with a healthy tolerance for risk.

This was evident from the joint political-military decision to prosecute an "Afghan-friendly" strategy despite the politically nettlesome issue of higher US casualties; and from Obama's swift decision that the general had unacceptably violated propriety in making public the fissures between top US policy-makers.

For those who missed last week's drama, General McChrystal and his personal staff -- styling themselves in the macho moulds of The Dirty Dozen and Inglourious Basterds -- committed the breathtaking mistake of embedding a writer for Rolling Stone magazine into their inner circle for a month, letting him listen in on formal and informal conversations with apparently everything on the record.

What Truman did with MacArthur

Image: MacArthur with President TrumanPhotographs: Rediff Archives

Although McChrystal's sacking will be a studied chapter in US civil-military relations, Obama's was an easy decision compared to the dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur by President Harry Truman in 1951.

MacArthur, the hero of two world wars, a winner of the Medal of Honour (America's Param Vir Chakra), and the de facto ruler -- American Shogun -- of Japan from 1945-50, had been recalled from Tokyo in 1950 to command the UN forces in Korea.

Angered by China's intervention in the war, MacArthur publicly challenged Truman's restraint by planning nuclear attacks on Chinese air bases.

An outraged Truman rejected warnings that MacArthur might beat him in the 1952 presidential elections. Overruling support for MacArthur from the Secretary of Defence, General George Marshall, and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Omar Bradley, Truman ended MacArthur's career.

Indian Generals would never dream of functioning like McChrystal

Image: Indian tanks participate in a war gamePhotographs: Reuters

All of this is unthinkable in India, where the system produces generals (and that includes flag officers of the navy and the air force) who would never dream of functioning like Stanley McChrystal.

That might indicate a healthier civil-military relationship in India, but only if one were to look superficially at just the Rolling Stone fiasco. Looking deeper -- especially at McChrystal's, and now Petraeus' selection as commanders in Afghanistan based on clear strategies that they brought to the table -- India could learn much from the US civil-military structure, based as it is on meritocracy, responsibility and accountability.

Consider how India would have selected a commander for a hypothetical Afghanistan mission: the MoD would have asked the Indian Army to "post" a suitable general.

In the US, the president nominates key commanders, based on their achievements and abilities, and Congress ratifies those appointments. General Petraeus, for example, was nominated as US Central Command chief, superseding several compatriots, after framing a widely acclaimed counter-insurgency doctrine for the US military. American generals routinely leapfrog less talented officers while being appointed to higher ranks.

Why Indian military rejects US-style selection

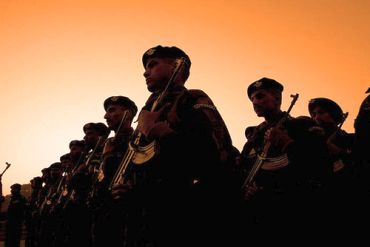

Image: Indian commandos take part in a paradeBut, in the poisoned relationship between India's military and the bureaucratic-political elite, the armed forces reject US-style "deep selection".

India's military suspects that political interests would run rampant, promoting well-connected officers rather than competent ones. The army remembers Lieutenant General B M Kaul, whose connections with Nehru allowed him to drive India to defeat at the hands of China in 1962.

This would be valid reasoning, were it not for a growing phenomenon: increasingly mid-ranking and senior officers are seeking political and bureaucratic patronage. The media has already reported instances where the Akali Dal and certain UP parties have lobbied on behalf of senior military officers. Bureaucrats too often approach the MoD to push the cases of nephews, nieces and country cousins.

So, allowing an institutional gulf between the military and the political-bureaucratic class, even as patronage thrives below the radar, amounts to getting the worst of both worlds: condoning patronage while preventing partnership. The Indian military's insularity -- with officers carefully shielded from outside influences, and shaped instead by a numbing professional uniformity -- prevents the development of commanders who can operate confidently at political-strategic levels.

The military may have a point

Image: An unidentified Indian general makes an aerial survey near the LoCPhotographs: Reuters

While US generals like Petraeus and McChrystal gain credit for doing PhDs and MPhils, and for being cerebral academics, India's armed forces give no credit to an officer for non-military qualifications.

And the question of seconding officers to other government and non-government organisations to obtain a wider perspective is dismissed with: the MoD will never allow it.

There, the military may have a point. Political and bureaucratic elites fear, deep down, that allowing officers out of the cantonments could open the door to a rampantly political military. And so the two arms of government -- civil and military -- occupy separate worlds in India, glowering at each other across an abyss of distrust.

Interaction is minimal, even in formulating national security policy; bureaucrats and diplomats do that for elected leaders who remain, for the most part, strategically unschooled.

Bred in the tradition of the freedom struggle, they see political agitation as a more potent and familiar instrument than military power -- a confusing and technical subject that is the preserve of an English-speaking elite that they don't identify with.

article