This article was first published 14 years ago

Home »

News » How US failed to stop Pak from going nuclear

How US failed to stop Pak from going nuclear

Last updated on: December 22, 2010 14:04 IST

Image: Pakistani nuclear-capable surface-to-surface ballistic missiles Shaheen II, with a range of 2,000 km. Inset: Former US president Jimmy Carter

Photographs: Reuters

Despite persistent anxiety over its nuclear programme, the Jimmy Carter administration failed miserably in efforts to dissuade Pakistan from fuel enrichment and officials were left "scratching their heads" on how to tackle the problem, newly declassified documents have shown.

The recently declassified United States government documents from the Jimmy Carter administration, published on the Internet on Wednesday by the National Security Archive, shed light on the critical period in the late 1970s when the US first became aware of Pakistan's nuclear intentions.

The documents show that the Pakistani nuclear weapons programme had been a source of anxiety for American policymakers ever since the late 1970s, when Washington discovered that metallurgist A Q Khan had stolen blueprints for a gas centrifuge uranium enrichment facility.

...

Image: Pakistan's nuclear-capable air-launched Ra'ad cruise missile

Photographs: Mian Khursheed/Reuters

The publication of the declassified documents comes at a time when WikiLeaks cables reveal the tensions between the US and Pakistan on key nuclear issues, including the security of Pakistan's nuclear weapons arsenal and the disposal of a stockpile of weapons-grade, highly-enriched uranium.

Analysing the series documents of the late 1970s, the National Security Archive said the then Carter administration helped prevent a deal that would have given Pakistan plutonium production capability, but discovered that it could not do much to prevent that country from producing nuclear weapons fuel with the "dual use" technology that the Khan network was acquiring.

Image: The Hatf VII Babur missile takes off during a test flight by Pakistan

Senior US officials concluded that the prospects were "poor" for stopping the Pakistani nuclear programme, and within months arms controller were "scratching their heads" over how to tackle the problem.

The declassified documents disclose the US government's complex but unsuccessful efforts to convince Pakistan to turn off the gas centrifuge project.

Besides exerting direct pressure on military dictator General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Washington lobbied key allies and China to pressure Islamabad, but also to cooperate by halting the sale of sensitive technology to Pakistan.

While Washington tried combinations of diplomatic pressure and blandishment to try to dissuade the Pakistanis, it met with strong resistance from Pakistani officials who believed that the country had an "unfettered right to do what it wishes".

Image: Pakistan military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq

By January 1979, US intelligence had estimated that Pakistan was reaching the point where it "may soon acquire all the essential components" for a gas centrifuge plant. Also, in January 1979, US intelligence pushed forward the estimate for a Pakistani bomb to 1982 for a "single device" (plutonium), and to 1983 for the test of a weapon using highly-enriched uranium, although 1984 was "more likely".

On March 3, 1979, Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher spoke in "tough terms" with General Zia and Foreign Minister Shahi. The latter claimed the US was making an "ultimatum".

On March 23, 1979, senior-level US state department officials suggested to secretary of state Vance possible measures to help make the "best combination" of carrots and sticks to constrain the Pakistani nuclear programme, nevertheless, "prospects (were) poor" for realising that goal.

Image: Pakistani Taliban fighters are equipped with state-of-the-art arms and ammunition

Photographs: Reuters

The decision in April 1979 to cut off aid to Pakistan because of its uranium enrichment programme was conflicted by state department officials, who believed that a nuclear Pakistan would be a "new and dangerous element of instability," but also wanted good relations with the country, a "moderate state" that had contributed to regional stability.

In July 1979, Central Intelligence Agency analysts speculated that the Pakistani nuclear programme might receive funding from Islamic countries, including Libya, and that Pakistan might engage in nuclear cooperation, even share nuclear technology, with Saudi Arabia, Libya, or Iraq.

By September 1979, officials at the arms control and disarmament agency said that "most of us are scratching our heads" about what to do about the Pakistani nuclear programme.

In November 1979, Ambassador Gerard C Smith reported that when meeting with senior British, French, Dutch, and West German officials to encourage them to take tougher positions on the Pakistani nuclear programme, he found "little enthusiasm. to emulate our position".

Image: Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and his Pakistani counterpart Yusuf Raza Gilan

Photographs: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

In the wake of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, when improving relations with Pakistan became a top priority for Washington, according to CIA analysts, Pakistani officials believed that Washington was "reconciled to a Pakistani nuclear weapons capability".

The National Security Archive concluded that the case of Pakistan shows how difficult it is to prevent a determined country from acquiring advanced technology to build nuclear weapons.

"It also illustrates the complexity and difficulty of nonproliferation diplomacy: other political and strategic priorities can and often do trump nonproliferation objectives," it said.

"The documents shed light on a familiar problem: a US-Pakistan relationship that has been rife with suspicions and tensions, largely because of Washington's uneasy balancing act between India and Pakistan, two countries with strong mutual antagonisms, a problem that was aggravated during the Cold War by concerns about Soviet influence in the region," the statement said.

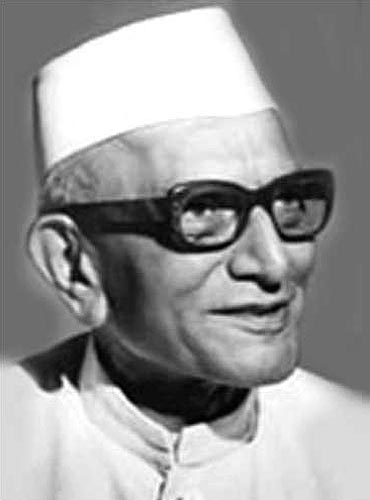

Image: Former Prime Minister Morarji Desai

Refusing to enter into any formal agreement with Pakistan on non-use and non-development of nuclear weapons, the then Indian Prime Minister Morarji Desai had told the US in 1979 that if Islamabad exploded a nuclear bomb, he would act to "smash it," a declassified US memo shows.

The conversation that transpired between Desai and the then US ambassador to India Robert F Goheen in a one-on-one meeting in June 1979 have been made public as part of a series of declassified documents on Tuesday.

The meeting with Desai that lasted for about 55 minutes was held at the instance of Goheen who was following the direction of the National Security Council of the White House to meet the prime minister on an "informal, exploratory and non-committal" basis.

Starting with the premise that Washington wanted to work with New Delhi to "deflect" the Pakistani nuclear threat, Goheen could get across the idea that "India is an essential part of any solution".

Desai, however, was not interested in the idea of a joint agreement on the non-use and non-development of weapons, the cable said.

Image: India's BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles, jointly developed with Russia, have a range of 290 km

Photographs: Reuters

Another declassified secret memo, about a June 29, 1979 meeting of National Intelligence Officer presided over by the then CIA Deputy Director Frank Carlucci, said "Indians would be strongly motivated to prevent acquisition by the Pakistanis of a nuclear capability by military force".

According to another declassified document of July 1979, with the Pakistani nuclear programme moving forward, National Intelligence Officer John Despres believed that India was likely to move more quickly in producing an "acceptable nuclear weapon," although it would take "at least two years".

If diplomacy did not check the Pakistani nuclear programme, India was likely to "improve its unilateral military options" to take preventive action, but "pre-emptive air strikes" would not be on the table unless the production of a Pakistani bomb was imminent or Pakistan had acquired "an invulnerable capability to stockpile" fissile materials, it said.

Source:

PTI© Copyright 2025 PTI. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of PTI content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent.