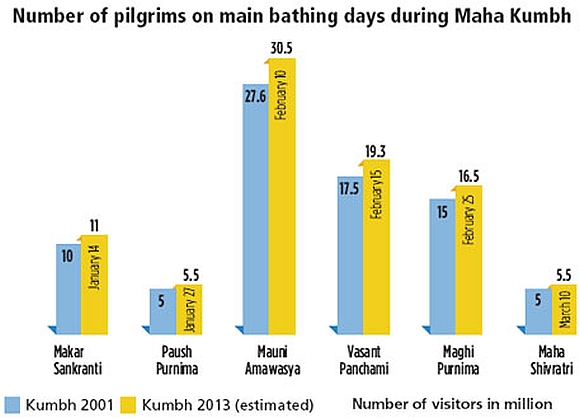

Billed as the largest gathering of humanity in recorded history, Maha Kumbh has commenced in Allahabad. Over the next few weeks, pilgrims will jostle to take a dip at Sangam—the confluence of two polluted rivers of the country, the Ganga and the Yamuna. Bharat Lal Seth analyses why the rivers will remain dirty.

The 55-day-long Maha Kumbh has brought the Ganga some relief, though short-lived. Just before daybreak on the first day of the festival, the river was relatively clean and with substantial flow. But this picture of India's longest river will last only till the festival lasts.

To placate the estimated 100 million sadhus, pilgrims and tourists attending the Maha Kumbh, the state government is following a three-pronged strategy to keep the Ganga clean and flowing. In keeping with the order of the Allahabad high court, which has been monitoring pollution in the Ganga following a public interest petition in 2006, the government is releasing water from upstream reservoirs, treating sewage in Allahabad before releasing it into the river and has curbed effluent discharge from industries upstream.

As a result, the quality of the water at the confluence has improved, says Sanjeev Gogia, founder of Aaxis Nano Technologies. The company, based in Delhi, monitors water quality of the Ganga every 15 minutes at eight places along its course on behalf of the Central Pollution Control Board.

Data from the state pollution control board shows by 6 pm on the day of Shahi Snan, BOD leveles in the water of the confluence had risen to 7.4 mg/l, up from 4.4 mg/l from the previous day. "This increase is mostly due to mass bathing," says Gogia. "But it is insignificant when compared to the pollution load discharged by industries."

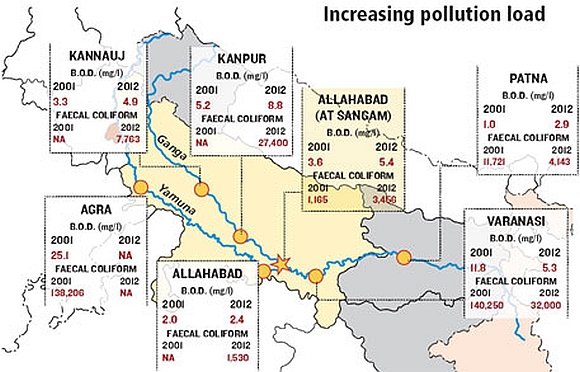

Before reaching the confluence in Allahabad, the Yamuna is the sewage receptacle for several towns and cities, including Delhi, although it is somewhat diluted by tributaries en route. The Ganga travels through several cities and industrial areas, including the leather hub of Kanpur. Every day, it receives approximately 250 million litres of industrial effluents and 1.3 billion litres of partially treated sewage (see map on facing page). At Allahabad, their confluence creates a cocktail of pollutants.

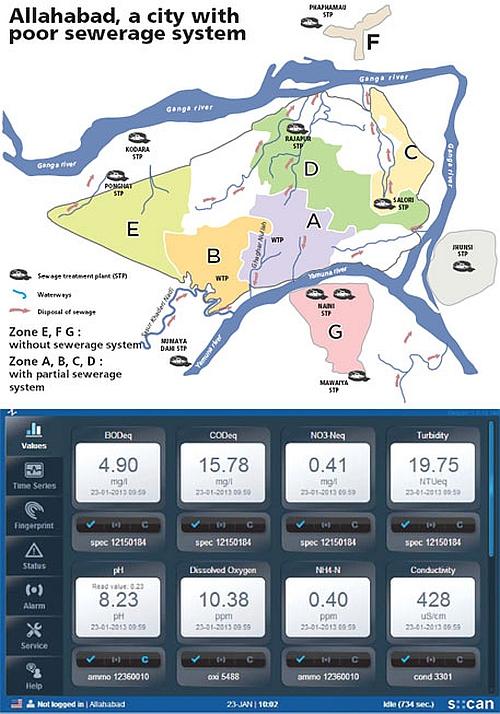

With its sewerage system in a shambles, Allahabad heightens the pollution levels. Water at Sangam has been deemed unfit for bathing since the 1990s.

...

Until December 31, 2012, the city had just two Sewage Treatment Plants with a capacity of 89 million litres a day (mld). This is about one-third of the sewage the city generates. These STPs were installed under the Centre's Ganga Action Plan, initiated in 1984 to check pollution in the river. Following the intervention of the high court in 2010, five more STPs have been installed.

They became functional just before the Maha Kumbh. Getting the administration to meet this deadline was difficult. In 2011 the court observed: "We are constrained to observe the state government, which is the ultimate authority to see that the people of the state are provided unpolluted river water, has been lethargic in taking significant steps to check the menace of tanneries discharge and sewage discharge enter the river untreated."

As of now, these seven STPs are capable of treating 211.5 mld of sewage. Their capacity will be bolstered by 42 mld by June. But given that Allahabad is one of the oldest and populous cities of the country, most areas remain unconnected to the sewerage system (see map).

"Besides, every now and then, political establishments allow illegal and unauthorised colonies," says L K Gupta, general manager, Ganga pollution control unit of Uttar Pradesh Jal Nigam. "Each year minor drains appear which carry raw sewage from these establishments and release it into the 57 storm water drains across the city that outfall into the Ganga or the Yamuna. On paper, Allahabad generates 240 mld of sewage but this is far less than the ground reality," he adds.

Now with directive from the judiciary, the authorities are mechanically lifting sewage from storm water drains and treating it in STPs. But for this intervention, four of the seven STPs would not receive a drop of sewage. They are running at full capacity as they are intercepting, diverting and pumping the sewage flowing in nearby drains.

"We will continue to do this until the yet-to-be-laid sewer lines bring sewage to the STPs," says Gupta, acknowledging that it is a pipe dream.

For the 35 untapped drains, the state government gave the go-ahead to employ a bio-remedial technique, which uses microbes to break down the organic matter. A Ghaziabad-based firm has supplied the microbial solution. The authorities admit that the bio-remedial technique is not a proven treatment practice as per the guidelines of the Ministry of Urban Development.

Yet, they say, the colour and odour in the drains have reduced markedly, and are expected to meet the prescribed discharge standards after treatment. The technique is likely to be discontinued on March 31, which means come April the 35 storm water drains will once again begin to discharge untreated sewage into the Ganga and the Yamuna. "The state government has sanctioned Rs 2.2 crore for the bio-remedial project just for the Mela period," says Gupta.

...

Ahead of the Maha Kumbh, the Prime Minister's Office also issued a directive to the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board, asking it to ensure that industrial unit 'comply with prescribed norms'. But making erring industrial units shut down is easier than getting them to comply with norms, say pollution control board officials.

The government decided to shut down all tanning units in the upstream city of Kanpur. On record there were 417 tanneries in Kanpur. Over the past two years, the administration has shut down about 100 tanneries as they were not meeting effluent discharge standards.

Many, however, continued to function as the pollution control board turned a blind eye to the discharge. Earlier this month the regional officer of the state pollution control board in Kanpur was suspended for not carrying out his duties. The government is playing hard ball, for the moment.

"Since January 10, people come at odd hours to inspect as if we are in the drugs business," says Imran Siddiqui, director of Super Tannery Limited, one of the oldest units in Kanpur. The units will begin functioning on February 14 until 22, remain closed for three days, resume functioning again on February 25 until March 5 and finally resume without restrictions only after March 10, when the Mela ends. Siddiqui says the closure will result in damages up to Rs 1,000 crore and affect nearly 100,000 people. "We are being made the scapegoat, while other industries continue to function," he adds.

"The four drains in Kanpur that carry the wastewater of tanneries do not have flow, at least in the day time," affirms Rakesh Jaiswal, founder of Ecofriends, a Kanpur-based non-profit that often monitors drains in the city for clandestine discharge. Gogia says the real time monitoring station shows the closure has had a noticeable impact downstream of Kanpur where BOD levels have reduced from 22-25 mg/l to about 6 mg/l in the past month.

The fallacy in such system of curbing pollution is that one cannot shut down a city. Kanpur generates over 400 mld of sewage, of which only 171 mld is treated. The remaining continues to be discharged untreated into the Ganga. The authorities only hope that it gets flushed out or diluted by the extra water released from upstream reservoirs.

...

The high court had asked the state government to make sufficient water available at ghats on the days of Shahi Snan, which receive the largest throngs of pilgrims and sadhus. Officials at the irrigation department claim they have been releasing 71 cumec of water from Narora barrage in Bulandshahr since January 1 and will continue to release the amount till February 28.

"We will release an additional 11 cumec of water around the six important bathing days," says A K Srivastava, superintending engineer of the state's irrigation department. The flow will be reduced to 43 cumec from March 1 until March 10.

A report by WWF-India in December last year says given the presence of such a large number of people, water must be released during the Kumbh period to maintain the environmental flows at the confluence. To achieve and maintain the desired depth of 0.9-1.2 metres for bathing, environmental flow at the confluence should be in the range of 225 to 310 cumec. The report has been submitted to the Uttar Pradesh government.

This is an ambitious target for planners. In January during non-Kumbh years, water flow of the Ganga is 142 cumec at Allahabad, which is much less than that of the Yamuna when it joins the confluence.

"If the Ganga is allowed to flow the way it is flowing during the Maha Kumbh, it will have serious impacts on drinking water and irrigation needs in the upstream catchment," says R K Srivastava, professor at the civil engineering department of Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology in Allahabad, who has a team studying the environmental impacts of the Kumbh gathering.

But the irrigation department did not do any studies to understand how the diversion of water from the Narora barrage for nearly two months would affect the rabi crop in the upstream catchments.

When the festival gets over, the barrage gates will close to hold back the waters, the pollution control boards will turn a blind eye to the discharge, clandestine or otherwise, from tanneries and other industrial units, and cities along the banks will continue to discharge untreated sewage into the Ganga. And the holy river will return to its usual way, sluggish, polluted and neglected.

...

"Pollution in the Ganga is an aesthetic issue for us. However, it is not for those who are dependent on her for irrigation and drinking water," says Sadhvi Bhagwati Saraswati, an American who is associated with Parmarth Niketan Ashram, the largest ashram in Rishikesh, since 1996.

This is the first time the Kumbh gathering is being termed "green" and environment has become the talking point at several religious discourses and among seers and sadhus. "People listen to religious leaders, which is why faith-based environmentalism will work," says Saraswati.

"Besides, one cannot talk to the common man in a scholastic way about pollution loads in a river." To keep the Ganga clean during the Mela period, Parmarth Niketan Ashram has launched an initiative, the Ganga Action Parivar. Every day sadhus and devotees associated with this Parivar clear out polythene and other rubbish thrown on the riverbank.

They are also organising meetings on the riverbank to make people aware of the pollution load in the Ganga and ways to improve its health.

Swami Chidanand Saraswati, head of Paramarth Niketan Ashram, plans to call a meeting, which will be attended by chief ministers of five states through which the Ganga crisscrosses. The meeting will discuss how to maintain the purity of the Ganga.

Several non-profits have also joined the nascent movement of faith-based environmentalism. "It was during the Kumbh of 2007 that I got the idea of spreading awareness of cleanliness, hygiene and pollution among a vast gathering," says Kusum Vyas, president of Living Planet Foundation, a non-profit based in the United States.

Some, however, are not as convinced of this approach.

"Green political thought is good but we cannot expect much improvement given the population increase and model of growth we have adopted," says M P Dube, dean of the faculty of arts and social sciences at Allahabad University.

The Sangam City itself is a classic example of this contemporary society, where a pop-up mega city is constructed and deconstructed within a matter of weeks. Maha Kumbh is no Olympics, which leaves behind a legacy of infrastructure.

Come March 10, the tents, stalls, offices, ghats and pontoon bridges will be dismantled. The 100 million people will leave behind a mountain of waste, excreta and plastics for the residents of the host city and downstream villages to deal with, for long.

...