'When it was all over. Nehru described the China war as a stab in the back. He was wrong. It was a stab from the front. He had only closed his eyes,' wrote M J Akbar in his book Nehru. The Making of India.

That in a nutshell sums up India's disastrous foreign policy towards China: a strategy that has changed little in terms of tangibles over the years. The 1962 defeat did alter our immediate perception of China. We now have our eyes open; we are wary of China but have failed to make the transition to sound pragmatism in the form of robust military prearrangements that such disillusion demands.

Commenting on India's parity with China, India's Navy Chief Admiral Sureesh Mehta recently remarked that it would be 'foolhardy' to compare India and China as equals in terms of economy, infrastructure and military spending. He went on to add that 'both in convention and non-conventional military terms, India neither does have the capability nor the intention to match China force for force.'

With regard to the future he counseled: "Our strategy to deal with China must include reducing the military gap and countering the growing Chinese footprint in the Indian Ocean region. The traditional or 'attritionist' approach of matching 'division for division' must give way to harnessing modern technology for developing high situational awareness and creating a reliable stand-off deterrent."

This professional assessment of India's lack of combat preparedness vis-a-vis China, as per the chief of the navy coming nearly 50 years after the debacle of 1962, reflects the cavalier attitude of the Indian political establishment to national security and is tantamount to negligence of the highest degree.

The admiral's blueprint of 'reducing the military gap and countering the growing Chinese footprint in the Indian Ocean region' if carried to fruitation will be distinct advantage when India sits down at the negotiating table with China to discuss cantankerous topics like the border disagreement.

Central to the India-China discord is a boundary dispute that focuses on two specific areas: Aksai Chin and Tawang, and dates back to British India.

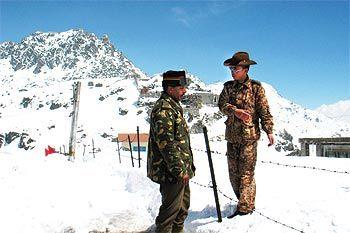

Aksai Chin is a desolate wasteland at the northeastern tip of J&K, an integral part of India at least since 1841, first as a part of Gulab Singh's princely state of Jammu and later as a territory of the British Empire. China continues to be in 'illegal' occupation of approximately 43,180 square kms in this region through which it has paved an access road to its distant province of Xinjiang. The construction of this road in 1956 was one of the factors that precipitated the Indo-China conflict of 1962.

China's capricious blow hot, bow cold attitude apropos these territorial issues must not be mistaken for a lack of seriousness. In fact it is an artful ploy, carefully calibrated to facilitate its nefarious agenda. For example, during the early 1950's China was at pains to convince India of the triviality of these concerns and the need for resolution at the local level. Once the Aksai Chin road was complete and the situation was 'ripe' as the then Chinese Prime Minister Chou En-lai put it, China changed its tune aggravating the issue by a rash of violent border incidents that culminated in the war of 1962.

Similarly China's present obsession with Tawang must set alarm bells ringing in South Block and alert India to the possibility of another Chinese shenanigan. Another clandestine venture could be in the offing.

On the eve of President Hu Jintao's high profile visit to Delhi in 2006, the Chinese Ambassador Sun Yuxi, erased any misperceptions India had about the actual territory in dispute by categorically stating: 'In our position, the whole of Arunachal Pradesh is Chinese territory and Tawang is only one place in it. We are claiming whole of that (Arunachal Pradesh). That is our position.'

In March of this year China opposed a developmental loan to India by the Asian Development Bank contending that it was meant for Arunachal Pradesh.

The genesis of the Tawang disagreement lies in the nebulous construct of the McMahon Line that separates the Tawang province of Arunachal Pradesh from the Tibetan region of China. The details of this demarcation were agreed upon at a tripartite meeting held in Simla in 1914 between Britain and the then independent government of Tibet with the Chinese in attendance.

Today, China refuses to accept the validity of the McMahon Line and accuses India of usurping 90,000 square kms of territory in this sector.

The Tawang area is crucial to India in that it protects Bhutan's eastern flank and provides strategic depth to India's north-east. Any territorial concession would firmly place the Chinese on the eastern planes with the potential to amputate the entire north-east. China's sometime offer to relinquish Aksai Chin in lieu of Tawang must be viewed with caution. What China has in mind is the barren wasteland devoid of the highway. Such a swap, a win-win situation for China is unambiguously a disastrous proposition for India

China's territorial disagreement with India is only the visible tip of a lethal iceberg, a subterfuge that camouflages a far more sinister game plan. While Pakistan's raucous hostility to India is steeped in history and stems from a fervent religious ideology the source of China' s animus is more mundane and subtle: an act of one-upmanship that is designated to show India in poor light lest it appropriates its role as the pre-eminent nation in Asia. For China this is an essential first step in fulfilling its consuming ambition of being perceived as a world super power.

The antagonism between India and China is akin to a sibling rivalry of sorts and goes back to the early 1950's. Both nations came into their own in the late 1940's, India in 1947 through Independence from the British and China in 1949 via the Communist revolution. Both carried the mantle of ancient civilizations, had vast populations endowed with superior intellect and a burning desire to reestablish their position in the world that had been wrongfully denied to them.

Despite its inner travails and the fratricidal vivisection that accompanied its Independence, India, in its early years exuded a moral panache that selected it out for special attention in the world, thanks to Mahatma Gandhi's spiritual persona and his non-violent freedom struggle.

Added to this was Jawaharlal Nehru's stature as a world statesman and his personal equation with prominent leaders of the emerging world like Yugoslavia's Tito, Egypt's Nasser and Indonesia's Sukarno: all of which contributed to India's visibility. Moving on, India conceived and assumed the stewardship of the Non-Aligned Movement which was consecrated at a meeting of leaders of Afro-Asian nations at Bandung in Indonesia in 1955.

The 1962 war, ostensibly a fallout of a contentious boundary dispute, was in reality the interim finale an intense rivalry, with the express purpose of cutting India down to size. Sarvepalli Gopal corroborates this in his authoritative biography of Nehru by quoting a Chinese official who explains that the prime objective of the 1962 war was to demolish India's 'arrogance' and 'illusions of grandeur' and that China 'had taught India a lesson and, if necessary, they would teach her a lesson again and again.'

Note the emphasis on 'again and again' which indicates that China is not averse to using a military option in the future.

Akbar rightly observes in his book: 'China's ambition to become the pre-eminent power of Asia, a dream that Nehru had usurped on behalf of India, was back on course after 1962.'

But the 1962 war was also the consequence of a flawed Indian approach. India's policy towards China was not based on hard realpolitik or grounded in reality. It was nurtured by large dollops of mushy sentimentalism that incorporated utopian axioms like lasting friendship, implicit trust and Third World camaraderie. Noble notions no doubt but concepts that are hardly expected to cut ice in hardnosed bargaining. The euphoria generated by the humbug chant of Hindi Chini bhai bhai only served to cloud India's perception of China and overlook its surreptitious tendencies leaving it ill prepared to face the treacherous assault on its eastern border. The supreme irony is that till the end, India's political leadership firmly believed that China would not attack India.

Give and take is intrinsic to diplomatic negotiations. But India in its naivete has always marched to a different drummer much to its own detriment. Appeasement is a mutant gene specific to the Indian psyche.

Manmohan Singh's blunder at Sharm El Shekh is not the first expression of this deleterious gene. It was very much in evidence during the Indo-Chinese dalliance. In 1954, India voluntarily recognised Tibet as a part of China willingly giving up its rights and privileges that it had acquired in Tibet from the British bereft of any quid pro quo. Concessions with regard to Aksai Chin and Tawang were not sought and not given. All India got in return was a commitment to the abstract notions outlined in the Panchsheel.

Now fast forward to circa 2009. Having humiliated India militarily in 1962 and surpassed India in terms of economic prowess, China now envisions the political destabilisation of India, the last facet of its overarching anti-India strategy. India's vibrant democracy and political stability continues to rankle China especially when world opinion devalues its overall progress because of its authoritarian regime and holds up India as a model of governance.

In line with this thinking was a recent article on a Chinese website. Despite the controversy over the true identity of the website and its import, the opinion piece does provide an insight into the Chinese thought process that cannot be ignored. Under the pretext of furthering social progress that is merely an eponym for expansionist ambition, the author urges China to initiate the balkanisation of India into 20-30 independent states with the aid of friendly countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan.

China is a dangerous cocktail of the past and the present. Hidden behind the reassuring fa ade of modern aspirations in tune with the changing world lies a ruthless medieval mindset that subscribes to notions of territorial expansion and international hegemony. That is a goal that China is determined to attain with either skillful guile or overt force if necessary even if it means violating the sovereignty of its neighbours or callously suppressing dissent within its borders.

A shrewd Sardar Patel rightly surmised in 1950 that Communism in China was an extreme expression of nationalism rather than its nullification. Nehru initially failed to heed his words but eventually came around to acknowledge this reality. In a speech to Parliament in the wake of the 1962 defeat he concluded that China was in reality 'an expansionist, imperial minded country deliberately invading another.' (Ramachandra Guha. India After Gandhi)

The late Chinese leader, Deng Xiaoping once said, "tao guang yang hui" which literally means to hide ones ambition and disguise ones claws. India needs to bear this dictum in mind when dealing with China. To dismiss war with China as a hallucination of India's jingoists would be a fatal mistake. Military parity or military deterrence at the minimum must be the compelling objective of our armed forces. Our political leadership must realise that its verbal bravado must be matched with military capability to be credible. We cannot afford to repeat the bumbling na vet of the late fifties that cost us dearly.