The family of Tushar Kolbe is unable to come to terms with his death in the 13/7 blasts. Prasanna Zore reports.

A year after Tushar Gangaram Kolbe, 28, died in the July 13, 2011 triple blasts in Mumbai, life has slowly gone from bad to worse for his bereaved mother, his unstable elder brother, Tushar's widow Tanuja and his father who shifted to Sanderi, their hometown in Alibaug after his son's death.

Not that the Kolbe clan had any happy existence when Tushar was alive.

You get a sense of how the Kolbes and thousands of other inhabitants like them live when you enter an overcrowded fish market that is one of the entry points that takes you to their house. The 10 by 10 square feet tenement with an attic that once accommodated eight people contains a small bathroom, an attached makeshift kitchen and no ventilation.

The main door opens to face their neighbour's wall in front, just about two feet away. A couple of drums that store water for three families block part of the front lane. The narrow space in between makes for the passageway. If one were to stand at the door inside the Kolbe household and look skyward through whatever space is available you get to see another neighbour's door that opens into a small eave, with supporting iron beams peering at you. The distance between these two walls is barely three feet.

In fact, this is how the entire cluster of houses that make for the Jai Hind Rahivashi Sewa Sangh in Kandivali (East), a north Mumbai suburb, have been constructed, making use of every available inch, open areas and breathing spaces be damned.

"We had a very hard time to get Tushar's body in and out of the house till the fish market," says Tushar's cousin Mangesh Bavreng, who lives just three doors away. The entire description of what lies in front, adjacent to and ahead of the Kolbe household was necessary to give readers a feeling how Tushar's last journey would have been through those congested lanes.

"But then we are used to such situations. Tushar wasn't the first one to die in our chawl," Mangesh adds quickly, abruptly breaking your imagination of the cremation scene.

Please ...

Tushar, who worked as a peon at a diamond trader's office in Panchratna, Mumbai's diamond hub, had been out with a few friends for a cup of tea and vada pav, the staple of umpteen Mumbaikars who live a hand-to-mouth existence.

"Shrapnel of the bomb severely damaged his legs and head. He died at around 11 pm on the same day," cries his mother just a day before her young son's first death anniversary. She turns down every request to tell her name.

'Why do reporters have to do it? Why is it so important to chronicle broken, shattered, traumatised lives coming to terms with the loss of their husbands, sons...?' my guilt takes over the duty of a reporter.

"What do you want me to say about my son?" she breaks down, snaps at you, not really wanting you to continue with the conversation. Your guilt multiplies.

"That is how she has been behaving ever since she lost Tushar," explains Pandurang Maske, Tushar's neighbour, who has been with the family through thick and thin and whose house wall faces the Kolbes' door.

Tushar's mother worked as a housemaid when he was alive to help him look after the family's needs. But fate took its ugly turn for her. It was not only the shock of Tushar's sudden demise that she had to bear. After Tushar she had to witness the death of her grand daughter and then her daughter. "They both died of fever a couple of months after Tushar's death," Maske says.

To add to her sorrows, her eldest son Sachin, a casual worker, has not been keeping well since last five years. "He works off and on. At times he stays in his house for days together," Mangesh adds.

"I don't know what has happened to him," says Tushar's mother maintaining her composure about Sachin, who looked very disturbed and left a few minutes after this correspondent entered the home.

When Tushar joined as a peon some eight years ago at Pancharatna he drew a salary of Rs 3,500 according to Mangesh. "He must have been earning Rs 7,000 or Rs 8,000 when he died, I think," says Mangesh when asked about Tushar's financials. His mother earned Rs 2,000 working as a maid at people's houses.

"Now, Sachin's wife works as a maid. Tushar's wife Tanuja too works at an imitation factory in the area but I am not sure what they earn now. His father stays depressed and spends most of his time at Sangeri," says Mangesh.

Try talking to Tushar's wife and she flatly refuses. She gets engrossed in washing clothes in the bathroom and lets Mangesh, Maske and her mother-in-law do all the talking.

Ask Tanuja if they got the compensation promised by the state and central government and she points towards her mother-in-law.

"We did get Rs 5 lakh within two months of Tushar's death," says the old lady.

"But the family got just two cheques of Rs 7,000 from the Tatas instead of six," informs Maske who perhaps is in the know of the matter.

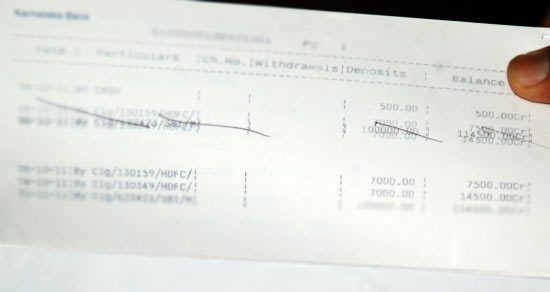

He asks Tanuja to bring her bank passbook to show the entries. Tanuja climbs up a slender iron ladder up to the attic and gets the passbook.

When told that the Jains of Dahisar got all the six instalments and they too should have got it, Mangesh says that a lady from the Taj Public Service Welfare Trust that dispensed the compensation told him after the first two instalments (in August and September) that the rest of the money will be disbursed after a meeting that was to be held two months later. (When rediff.com contacted the lady in question she said that the money was directly credited into Tanuja's bank account.)

But the family, most of them uneducated and without much understanding of banking transactions, had not followed up with the lady.

When this correspondent informed Mangesh about the same he asked Tushar's father to go to the bank and get the passbook updated. The money was in Tanuja's account.

It seems the family, steeped in their sorrows and in their efforts to get along with life had forgot to update the passbook after October 2011.

A chance interview with the Kolbe clan helped them find Rs 28,000 which lay in Tanuja's account but everybody in the family was oblivious too. While it may not last them forever it certainly would help ease the family's burden for a couple of months.

Mangesh calls back to say 'thank you'.

Is this why reporters chronicle the lives of victims and their families?

The guilt has just somewhat lessened.

...