The Indian high commission in London is making efforts to take the manuscript to India for display. Ashis Ray reports.

Photographs: Courtesy Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

If diplomacy and persuasion succeed, there could be an historic homecoming, albeit temporarily, of the Bakhshali Manuscript -- the oldest recorded evidence of the origin of the zero symbol, an Indian invention.

A government source disclosed the Indian high commission in London is making efforts to take the manuscript to India for display. It remains to be seen if the Bodleian Library, owners of the priceless document, grants permission to ship such a precious item all the way to India.

Meanwhile, a folio from the manuscript was shown for the first time at a public exhibition as 'Illuminating India: 5,000 Years of Science and Innovation' opened at the Science Museum in London recently. The famous Bodleian Library is at Oxford University, which is Britain's most ancient seat of learning and one of the leading places of higher education in the world.

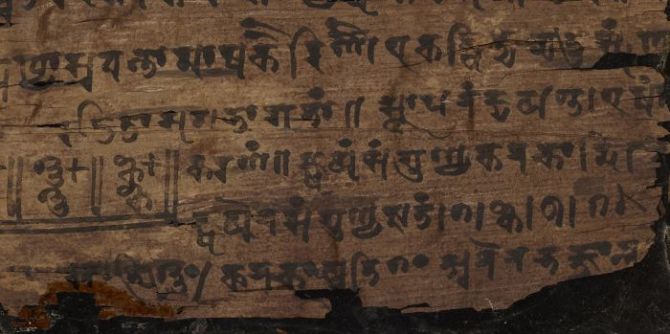

The Bakhshali Manuscript -- about 300-800 CE -- was unearthed in 1881 by a farmer near the village of Bakhshali, which after the partition of India in 1947 is a part of Pakistan.

The curator at the Science Museum said: "Researchers soon realised the manuscript was one of the most significant discoveries in the history of mathematics."

It is the earliest example of the numeral zero ever found. Although it tends to be taken for granted, without the concept of zero the entire system of mathematics -- and the technologies that depend upon it -- would not be possible.

Speaking at the opening of the exhibition, Ian Blatchford, director of the Science Museum, described the Taj Mahal in India as 'the greatest unity of art and science ever created'. He added it was his ambition to exhibit an authentic replica of the monument at his renowned institution.

'Illuminating India' is a manifestation of the India-United Kingdom Year of Culture being celebrated in Britain to mark the 70th anniversary of Indian independence.

It portrays objects originating from the Indus Valley Civilisation in 3,000-2,500 BCE to a payload developed for launch this year by the Indian Space Research Organisation.

It depicts the renaissance of Indian mathematics and science during British rule, with the surfacing of Jagadish Bose, Satyendra Bose, S Ramanujan and C V Raman.

The exhibits are a mind-boggling tapestry of riches, which Indian diplomats have encouraged, but which the Indian government, other than underwriting the transportation of some items from India, has played no role in financing.

Indeed, the India-UK Year of Culture has been another glaring case of a disappointingly fulfilled commitment on the part of the Narendra Modi government.

The celebration was announced during Modi's visit to London in November 2015. But there was apparently no certainty about funding from New Delhi until Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s announcement in his Union Budget in February of this year.

Besides, the allocation eventually granted was reportedly one-third of the projected requirement, leaving the high commission and its cultural wing The Nehru Centre running from pillar to post to mount a respectable commemoration with help from British bodies and private sources.

Last but not the least, the actual conveyance of monies was delayed and the full transfer is said not to have taken place till date.

Some of the efforts have been commendable, such as Sukanya, an opera written by the late Ravi Shankar which is dedicated to his wife.

However, there's a hot debate about whether, overall, the 2017 India-UK Year of Culture has matched the 1982 Festival of India and if it has made the same impact on the British public.