This month saw releases of two much-hyped books, both of which went on immediately to become best-sellers.

Both were by authors in their 40s, expected to shed much light, but did not quite succeed in doing so.

Both authors were incidentally Maharashtrians, well-known to each other.

One was by God, aka Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar.

This review, says Shreekant Sambrani, is about the other.

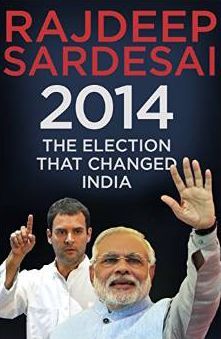

Rajdeep Sardesai's maiden book on this year's general election has received much media attention (led chiefly by the channel with which he is currently associated) and is reportedly a bestseller.

Rajdeep Sardesai's maiden book on this year's general election has received much media attention (led chiefly by the channel with which he is currently associated) and is reportedly a bestseller.

That will surely make him a ton of money but, to this reviewer, the more important consideration is whether the book lives up to the key phrase in the title, The Election That Changed India.

I must confess that after reading the book with its large compendium of oft-told tales about elections and politics past and present, I am no better informed about why and how this election has changed India than I was before.

The book takes us on a guided tour of Campaign 2014, starting with the origins of the two supposed contenders, Narendra Modi (right) and Rahul Gandhi.

We visit a 'government in ICU' that sets the backdrop to the elections and go through the heartland, meet the by now all too well-known dramatis personae of the various parties, sample media flourishes before witnessing the tsunami (author's description).

For afters, Mr Sardesai throws in his take on the first months of the Modi prime ministership and a statistical appendix courtesy the Election Commission and the Centre for Study of Developing Societies.

Mr Sardesai warns us what to expect: 'This book... isn't written by a political scientist or a psephologist... But (it) provide(s) the best seat in the house... to meet, observe, understand all kinds of people.'

It does, to a large extent, but so did millions of words of print media and minutes of news television.

He also refers to Mr Modi's presenting himself as the first post-liberalisation politician. The reader expects at least some exploration of this, preferably of a nuanced and in-depth variety. What we get in the relevant chapter instead is the logistics of alliances and campaign tactics presented as strategy.

We go through page after page of who met whom, who gave what sound bytes, and what people told Mr Sardesai, on or off the record. Never do we delve into the core of Mr Modi's appeal, the perceived success of the Gujarat Model, which was seen as being 'foreign-like' with assured 24x7 power, good roads and water managed from its own resources.

We are also treated to a potted biography of Mr Sardesai, the political reporter and editor/anchor. In fact, there is so much of the author throughout the book that an appropriate subtitle for it could have been How I Covered the Election.

Contrast this with the classic analyses of Theodore White's The Making of the President (the original, covering John F Kennedy in 1960) and Joe McGinniss's The Selling of the President in 1968.

The two trendsetters provide the reader not necessarily learned socio-political commentary of contemporary America, but actually discuss electoral strategy going far beyond regurgitating what was common knowledge all along.

Even Joe Klein's Primary Colors, a fictionalised account of Bill Clinton's first campaign, gives us a gist of what the unifying strategy was, notwithstanding its somewhat salacious details.

All of these were works of members of the tribe to which Mr Sardesai belongs, namely, political commentators.

A part of the problem is in the oxymoronic nature of the work Mr Sardesai (left) attempts: instant history.

A part of the problem is in the oxymoronic nature of the work Mr Sardesai (left) attempts: instant history.

History implies passage of time to develop distance and balanced perspective. Instant does not require looking back at current events.

Instant histories are interesting mainly because they throw up nuggets of insights otherwise not widely known. The high water mark in this genre remains Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, which took the reader on a tour de force of the psyches of Kansas murderers based on their trial in 1966. More relevant is Mr McGinniss' revelation of the disdainful manipulation of American voters by the Nixon campaign and its advertising.

The nugget that Mr Sardesai throws out -- that the Vishwa Hindu Parishad international working president, Pravin Togadia, was the real ringmaster of the 2002 riots and the Modi government was merely incompetent -- does not quite pan out.

The VHP incited the people, but notwithstanding what the Nanavati commission has inferred, the fact that the police largely looked the other way would not have been possible without some higher-ups in the government acquiescing to it.

Mr Modi was too new in his job, still not quite trusted. Popular speculation then as now pointed a finger at a cabal of senior ministers led by the late Ashok Bhatt. Gordhan Zadafia, a Modi minister who fell out with him, testified before the Nanavati commission to this effect in February 2013.

A journalist of Mr Sardesai's standing owed to himself and his readers a thorough check of these matters of record before rushing to judgement on Mr Togadia as ‘the real boss of Gujarat’ in 2002.

Mr Sardesai is also unfair in crediting the concept of the opposition unity index to Prannoy Roy and Dorab Sopariwala. The pioneering Indian psephologist E P W da Costa had brilliantly analysed the elections of the 1960s using this construct.

Mr Sardesai himself provides, albeit completely unintentionally, the basis to judge his effort.

He mentions the many interactions he has had with Mr Modi over the years, including the one in the Gujarat 2012 campaign tour when he got the cold shoulder after he raised the issue of 2002 riots. He says Mr Modi did not return his congratulatory call on May 16 this year, nor has he been given an audience.

That speaks as eloquently about the prime minister's preferences as it does about the judgement of the spinmeister.

The reviewer is a long-time observer of Indian elections and Narendra Modi.

You might also like to read

Rajdeep Sardesai: I've never been anti-Modi

Photograph, Rajdeep Sardesai: Abhijit Mhamunkar.