The collector king Sayajirao Gaekwad III, who lived a century ago, put together a fantastic world of Indian and European art for his subjects.

I’ve been fascinated with Baroda’s Sayajirao Gaekwad III ever since I opened my first book on Raja Ravi Varma and learnt how the 19-year-old maharaja invited the painter to Baroda (now Vadodara) on the suggestion of his diwan, Sir TR Madhvarao, in 1881.

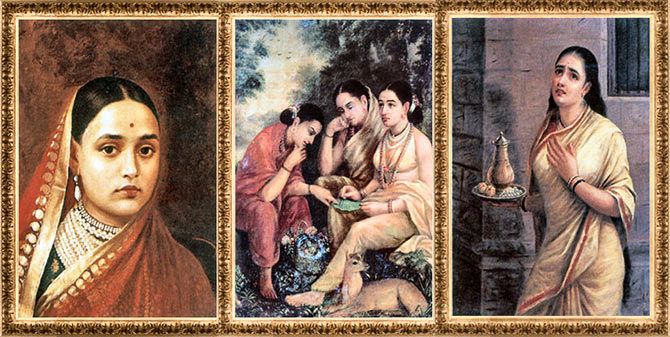

The painter was to make the prince’s ceremonial portrait for his investiture. But he stayed on to paint some 44 of his best works over the next four years.

Legend has it that the young prince agreed to the painter’s request to display his mythological paintings for the common people of Baroda. These were exhibited in the gigantic Darbar Hall of the newly-built Lukshmi Nivas Palace (spelling as per the palace's records).

More than 600 people shuffled through the Darbar Hall, quietly, every day, staring at the paintings, leaving behind coins as a sign of their devotion.

This, it seemed to me, was the point when art made religion accessible to the common man in India. It was brought about by a young king who had been raised as an illiterate cowherd but was adopted by the widow of the previous king, around ten years earlier.

Ravi Varma had such regard for the maharaja that, many years later, he wished for him to be the chief guest at the house warming of his new bungalow in Kilimanoor, Kerala. Unfortunately, Varma died before it was completed.

Sayajirao Gaekwad III was exceptional, especially in terms of what he offered his people. He paid for the young Bhimrao Ambedkar’s education. Dadabhai Naoroji was his diwan in 1874. He offered Sri Aurobindo a job when he met him in England; Sri Aurobindo finally joined the Baroda Service in 1893.

He was also a patron of Indian classical music. Ustad Moula Bux founded the Academy of Indian Music under his patronage in 1886, and his court boasted great artistes like Ustad Inayat Khan and Ustad Faiyaz Khan.

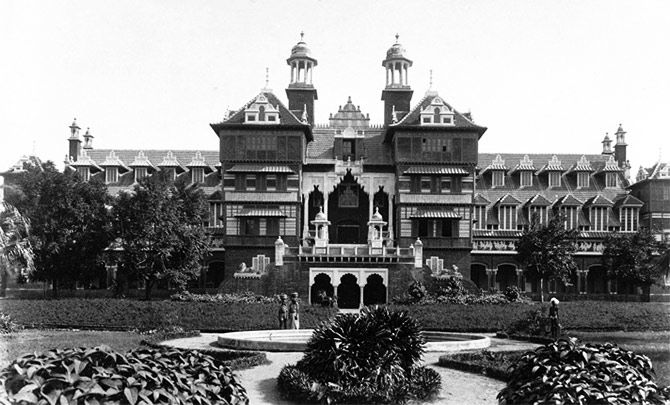

He built the Lukshmi Nivas Palace for himself and to house his art collection, which is inspired by great collectors like Cosimo de' Medici. In 1890, the palace cost around £180,000. It’s said to be four times the size of Buckingham Palace and the grounds were landscaped by William Goldring, a specialist from Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, near London.

Parts of it, including the huge Darbar Hall, the Elephant Room, the Throne Room, armoury and main portico, are open to the public.

The Darbar Hall has a Venetian mosaic floor, Belgian stained glass windows with images from Indian mythology and walls with intricate mosaic decorations. The portico has teak terraces, marble floors and sculpture by 19th century Italian sculptor Augusto Felici.

Weapons that belonged to Shivaji and Aurangzeb are kept in the armoury and there are images of gold and silver cannons that were once created for the kingdom.

The plainest thing in the public rooms is the Gaekwad’s throne that has a white pillow and is topped by a silver umbrella with a peacock worked into it.

But, perhaps the most prized gifts from the raja to Baroda were two museums. Fatehsinh Museum is located on the grounds of the Maharaja Palace and was once the school for the maharaja’s children.

Inside, instead of the small family museum I expected, I found a huge structure filled with art from all around the world. Established in 1961 by the scholar Hermann Goetz , it has some breathtaking sculpture like the Felicis.

The two that caught my eye the most, were of two cheetahs being taken out by their trainers for a hunt and of Rani Chimnabai II where you can see her pearls through the folds of her sari.

There are also copies of Raphael, Titian and Caravaggio’s most famous paintings, as well as copies of Greek and Roman statues that would not be out of place in the Uffizi Palace, the Medici home in Florence where the best art from the Renaissance emerged.

I went to the Uffizi Palace to see precisely these paintings and sculpture and it’s awe-inspiring to find them in India. There are rooms dedicated to Ravi Varma.

There’s also a single painting by the artist some claim was India’s greatest, Abdul Rahman Chugtai. You come upon it unexpectedly on a staircase, under which is a beautiful collection of miniatures from across India. There’s a collection of Vishnu statues from the 5th century as well as a collection of ceramics from Wedgwood, Lalique and Tiffany.

There’s even a room dedicated to European paintings from the early 20th century. This is the greatest let-down. After looking at great original art from India and copies of Italian masters in other rooms, these insipid paintings from Europe don’t really deserve to be here.

As Gujarati painter and art critic Gulammohammed Sheikh remarked, “The maharaja’s collectors made a mistake with these. During this period after World War I, they could have bought pre-Renaissance Italian art, and it would have been worth a fortune today.”

But it’s the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery that cemented the Gaekwad’s reputation as a collector for me. It was created by him to educate the people of Baroda on archaeology, natural history, geology, ethnology, art and history, along the lines of London's Victoria & Albert Museum and Science Museum. Like them, it was handed over to the city of Baroda to manage. Like all government museums in India, it’s not well maintained.

But it’s full of visitors. Just the fact that such a large museum exists at all shows how much the maharaja thought of his people and their need for education.

It was designed by R F Chisholm, who helped Major Mant design Lukshmi Nivas Palace, in 1894. It opened for the public in 1921. The First World War caused a delay in the transfer of the pieces from Europe.

The museum has a genuine Egyptian mummy as well as the skeleton of a blue whale. It has also got the inside of a Jain temple, palaeolithic art and costumes and textiles from Gujarat on display.

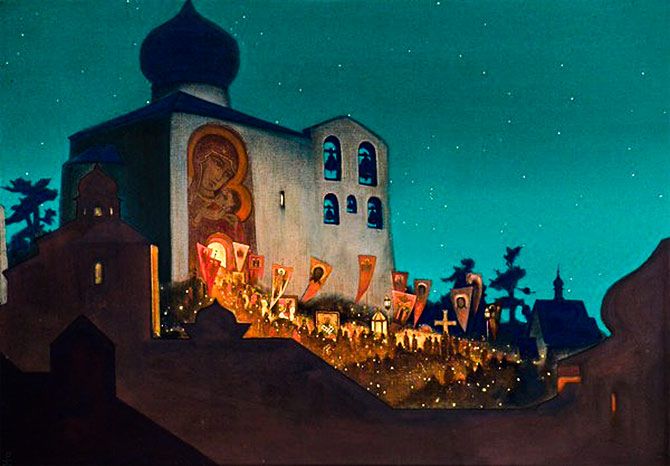

Its European art collection is bigger than the one in the Fatehsinh Museum. Several of the paintings are said to be original masterpieces by European painters like Paolo Veronese, Luca Giordano, Francisco de Zurbaran, JMW Turner, John Constable and Zoffany. There are paintings by Nicholas Roerich. There are some fine Mughal miniatures, and very valuable palm-leaf manuscripts of Buddhist and Jain origin, a full-fledged gallery of Tibetan art and several Persian texts including a tiny Quran that you need to read with a magnifying glass.

But what’s not to be missed is a room full of sculpture from the fifth century onwards. There are wonderful pieces from the fifth century Gandhara school of art. What I would travel to Baroda to see again would be the rare set of 68 Jain bronzes found nearby in Akota.

Florence, because of the Medicis and their habit of collecting great art, is the second most visited city in the world.

Here, in the small town of Baroda, I found a collector of fine things from a century ago.