After 48 hours of being sworn in as chief minister of Delhi, Arvind Kejriwal gets set to pass an executive order to provide 700 litres of free water to every household in the capital. Down To Earth analyses the challenges he is likely to face

Santosh Singh, a resident of Sangam Vihar and a worker at confectioner’s shop, was threatened with a gun the last time he talked about water facilities in his locality. All he had done to get such a treatment was to seek his neighbour’s support to ask Delhi Jal Board to provide a new tubewell for area.

The rogues from Delhi’s tanker mafia, which is paid a handsome amount by the residents for installing a borewell, sarcastically asked his wife whether Santosh had life insurance. He was unable to do anything to get water from DJB and his wife, till today, has to go and fetch water from private tankers amidst catcalls.

At times, even glass shards are thrown at his doorstep by the mafia men. Of the Rs 6,000 that Santosh earns, he is forced to pay Rs 400 to the mafia for getting access to water extracted from ‘government’ borewells.

So, even if Delhi’s new chief minister and Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal, who has promised 700 litres of water for free everyday to each household “wherever possible”, is able to fulfill the commitment, water would be free for Santosh’s employer who stays in Kalkaji, but Santosh will still keep paying Rs 400 or even double the amount just because he does not have a pipeline water connection provided by the government.

The party manifesto also says that water is the biggest concern for the ‘aam aadmi’ in Delhi as more than 50 lakh people do not get piped water in their homes. Kejriwal has ensured that all households in Delhi get water in their homes, irrespective of their location in slums, authorised or unauthorised colonies, and has clarified that a solution will be found for those who do not have piped water supply.

This, however, may mean that till the way out is not found, water sop to the people better off while the aam aadmi would continue to face water scarcity and end up paying a lot for the water he gets.

...

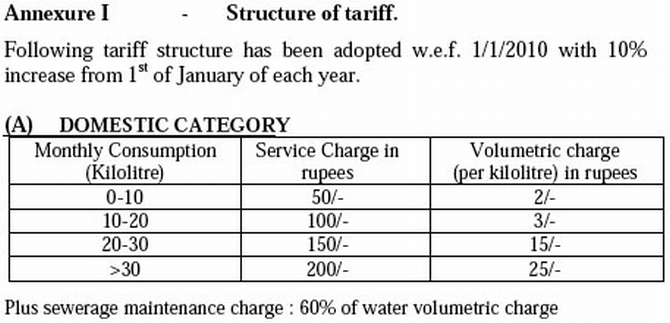

Considering that the average number of people in a family is five, the AAP promise means 140 litres per capita per day and 21kilolitre consumption per household per month. A household with this amount of consumption per month falls in the third slab of water tariff, which will now be subsidised.

According to government estimates, 30 per cent of Delhi’s 22 million population lives in urban villages and unauthorised colonies (called jhuggi jhopri or JJ clusters) and these areas do not have an official water-pipe connection.

Delhi has 14,000 km of extensive water pipeline network. But, only 68 per cent of city’s 2.5 million households s i.e. 1.7 million households have piped water connections while the rest of 38 per cent remains unreached.

About 25 per cent of the city area remains uncovered by piped water supply.

According to the recent National Sample Survey Organisation survey, 15.6 per cent of Delhi's urban households and 29.7 per cent of its rural ones don't get sufficient drinking water throughout the year.

The areas which do not have pipelines meet their water requirement through handpumps and tankers. Also, there are a few newly developed localities which do not have an official pipeline yet.

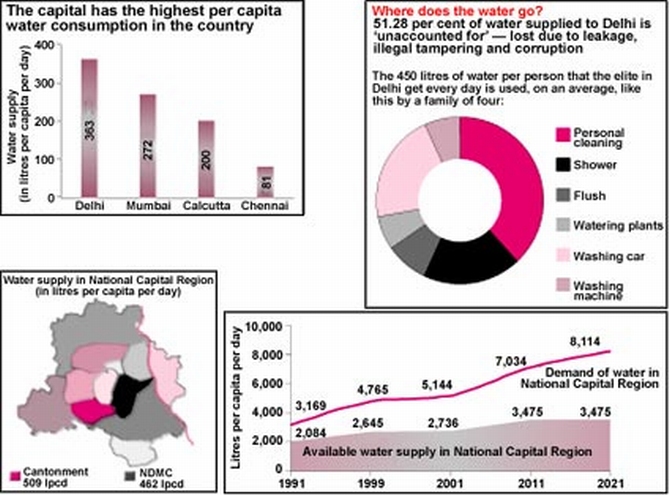

Here, the demand is met invariably through tankers or groundwater. This inequity in distribution leads to inequity in supply. The per capita availability of water in the city varies from shocking 29 LPCD in parts of outer Delhi such as Mehrauli to as high as 509 LPCD in the posh residential areas falling under the administration of New Delhi Municipal Council.

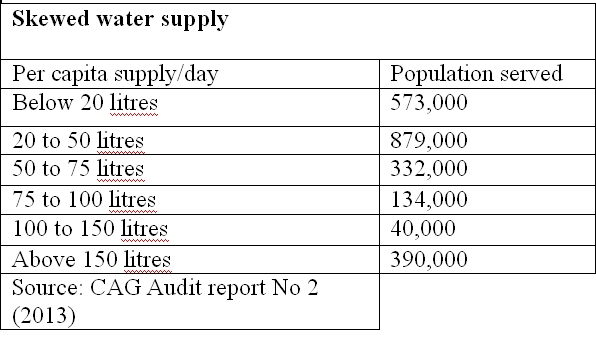

The Comptroller and Auditor General report, released in April 2013, had exposed the poor provision of public services to residents of Delhi and also pointed out at the inequity in water supply. It stated that 24.8 per cent of Delhi’s population is being supplied 3.82 litres per capita daily, which is far less than the minimum stipulated average of 40 litres, established by the World Health Organisation.

When the CAG carried out a study of the command area of the Nangloi plant, one of the six treatment plants for Delhi, it found the prevalence of iniquitous supply, ranging from three litres to more than 220 litres per person per day.

The DJB had defended this by stating that “large number of unauthorised growth in unplanned colonies in west and southwest Delhi has led to an unrationalised supply of water.”

“The DJB neither has a proper system to measure the water supplied to different areas nor does it have access to reliable data on population in different areas. It, therefore, cannot ensure equitable supply of water,” noted the report released in April.

To indicate the potential loss in revenues, less than 40 per cent of water produced was billed during last three years. Also, 679,000 connections (35 per cent) of the 1,964,000 water connections in the city are without functional metres. The DJB has plans to install 800,000 new meters, but the deadlines for these projects remain unclear.

...

According to the latest Delhi Economic Survey, the city has a network of about 11,350 km of water supply mains. But a significant portion of this is 40-50 years old and prone to leakages.

"Of the total pipeline-network length of 14,000 km, only 200 km was repaired in 2012-2013. Water loss due to leakage is as much as 45 per cent and there are issues such as inequitable distribution and lack of storage capacity. These issues cannot be resolved overnight,” said a senior official of the DJB. He also told us that Kejriwal had a meeting with DJB core officials on last Thursday.

In Sangam Vihar alone, the government has dug 118 borewells from where the residents have to draw water. However, these borewells are monopolised by the tanker mafia. Many have dried out due to exploitation over the years. If people such as Santosh raise their voice against the system, they are threatened and even beaten up.

The DJB, which manages about 250 water tankers itself, has partially outsourced the supply of water through tankers to three private corporations.

If a citizen calls an emergency number of the DJB to ask for water, it is obligatory for the board to send a tanker within three hours. But, citizens say that the emergency numbers are either non-functional or remain busy throughout the day.

Storage another problem

“Even if the pipelines are laid overnight, where will the people store 700 litres of water? The infrastructural flaws in the houses in these urban villages and unauthorised colonies are bound to trigger wastage. Especially when there is a huge gap between water availability and demand,” said the DJB official.

The DJB supplies about 835 million gallon daily whereas the current requirement of the city is about 1,025 MGD. A few reports suggest that the average supply in 2009-10, 2010-11 and 2011-12 was 800, 835 and 818 MGD respectively.

According to the CAG report, the untreated water that the DJB gets is not sufficient to meet Delhi’s demand. The shortfall is being met through private borewells and private vendors. The report makes several valid points regarding leakages in the system, lack of monitoring and measurement, and importantly the non-removal of silt from Yamuna at Wazirabad pond.

It also says that the pond, which is the source of water for Wazirabad and Chandrawal water treatment plants, can reduce its holding capacity due to deposit of silt to the extent of three to four feet. The last time the pond was dredged was in 2006.

The DJB replied to the CAG query on why the silt has not been removed yet by saying that “…not much expertise exists in Delhi”. The CAG report stated that “the reply is not convincing as dredging was carried out in 2006 as well.”

...

The ministry of urban development has set a benchmark for the per capita water usage at 135 LPCD. According to the AAP promise, every person would get 140 LPCD which including the leakage would stand at approximately 175 LPCD.

“Supplying 175 LPCD is too much and against global practice. This can easily be reduced to 110 LPCD with conservation efforts such as using mug and bucket in place of flush or shower and. This way, an individual in India would require maximum 50 to 60 litres of water every day and a family of five members would need only 350 litres,” said Manoj Mishra, convener of Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan.

He also suggested that instead of providing free water, the government should have tariff slabs and charge as low as 50 paise per litre for the first 700-litre bracket.

Apart from 700 litre free water, AAP manifesto also promises transparency in the functioning of the DJB, which presently keeps no account of how much water is being received from different sources and how much water is being supplied to each area.

Bulk meters would also be installed and the data gathered from them will be put on the DJB website every day. The party, which has openly opposed privatisation of DJB, has promised to clamp down the tanker mafia.

It is also committed to long-run solutions like city-wide rainwater harvesting, revival of Delhi’s water bodies and conservation and recycling of water.

Public participation for better sanitation

To connect provide sewage facilities to all households, irrespective of them being slums or unauthorised colonies, the party has assured construction of 200,000 community and public toilets and availability of small, decentralised sewage plants managed by Mohalla Sabhas.

The manifesto also says that waste would be managed with direct participation of people by encouraging separation of bio-degradable and non-biodegradable waste at the household level and imposing fines for littering.

“Let us hope for the best. I have been living here for the past 8-9 years. Every now and then I have had to wade through foot deep sewage water on the road along the DDAPark. We were convinced that we will have to wait for another eight or nine years to get proper sanitation and water facilities. So, waiting a few more months is not a bad idea at all,” says Prakash Varma, resident of Sangam Vihar.

“If Kejriwal keeps his promises, it could bring positive changes. But does he has enough time so make so many changes?” asks Mahesh Verma, a right to information activist.