A National Geographic feature on leopards in Mumbai has just gone viral on social media. But two years ago, Sumit Bhattacharya/Rediff.com met pioneering wildlife scientist Vidya Athreya, whose tracking of a leopard's stunning journey through Maharashtra shattered set notions about wild animals.

Did legendary hunter-conservationist Jim Corbett aggravate the man-eating leopard problem in Uttarakhand, where the big cats kill the maximum number of people in India?

Do leopards, believed to be solitary animals, communicate with each other? Do they live alongside people -- and not just in protected forests -- in villages and towns, and does capturing and moving them to forests lead to attacks on humans?

These questions will swarm you if you speak to Vidya Athreya, who has been studying leopards in Maharashtra for the last 13 years.

In 2009, she fitted the first radio-transmitter collar on a leopard in the state.

The elderly male cat, which she named Ajoba (grandfather in Marathi), was released in the Malshej Ghat forests. He straightaway started towards Mumbai, about 150 km away.

Over two-and-a-half months, Ajoba walked through villages, towns and the city -- crossing railway stations, industrial areas and swimming across a huge creek -- before settling down in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park that the Maximum City eats into a little bit more every day.

He never attacked a human being; very few people saw him. He was eventually run over by a truck on the Mumbai-Ahmedabad highway.

The cat's journey is being made into a Marathi film by National Award-winning director Sujay Dahake.

In Ajoba, Urmila Matondkar plays the wildlife scientist.

"The character that plays me is totally fictionalised, but it's based on my work," says Athreya, who lives in Pune with her astronomer husband, teenaged daughter and pet cat.

"The leopard is the hero. Not the scientist," she insists.

Please click NEXT for more...

First published on August 26, 2013.

Athreya -- who realised wildlife is her passion when she went to her first forest, the Annaimalai Hills in Tamil Nadu, in her late teens -- started studying leopards by coincidence.

After returning from the University of Iowa in the United States in 2001 -- "I really missed India, " she says -- she was living 75 km from Pune, where her husband was working on a telescope.

Leopard attacks in Maharashtra and the area began grabbing headlines.

At the time, she says, "The forest department had caught some 106 leopards from the croplands and they just left them in two little forested pockets -- the Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, which is like 100sq km, and Malshej which is even smaller. Within a week, the attacks started. In the next two years, there were some 50 attacks on people."

The areas had never had so many attacks.

"Everybody thought leopards are not supposed to be in farmlands; that they had strayed from the forests. So let's put them back," she says.

When she studied leopards in Maharashtra's Sangamner area with a team of three friends, she says, "I realised how fascinating it is. It's not just about wildlife and ecology -- it's a lot about people, and the interface between wildlife and people. Their culture comes into play, and politics, and society."

Around the same time, putting microchips in the tails of leopards in the Sangamner and Nashik areas was started. When she and veterinarian Dr A V Belsare began fitting captured animals with microchips (used for identifying animals), Athreya realised that none of them had attacked people, despite living in close proximity: "Big, 70 kg male, caught not because he had attacked people, but because he was seen in a sugarcane field!"

"It's unique," she says. "The world over, they are trying to figure out how to live with large felines. They killed all their large carnivores and generations of people have grown without them. Now, the conservation ethos has come in. We (India) already have people living with them, and we have no clue that we are special!"

Even in Africa, she says, "you don't have human densities like this at all."

Please click NEXT for more...

From Jammu and Kashmir in the north to Tamil Nadu down south, from Assam in the east to Gujarat in the west, leopards are found across India. Exactly how many does the country have? No one knows, Athreya says.

"There is this figure in a 1996 publication that said 14,000 leopards. It has no scientific basis. But there are a lot. Even if you want to count, it is going to be very difficult because a lot of them are living among people. They are found almost everywhere."

"We just take a map and say this is a protected area and people should not go there and animals should not come out. Nobody's told the animals that! In other countries they know because once they are outside they are killed."

"In India the killing is not so much. Not in these parts (western India). In the northeast, yes. So there you have silent forests at one-twentieth of the human density you have here."

She adds, "My guess is all human use rural areas in India -- which are not wolf landscapes (dry) -- all areas with habitat, like sugarcane, jowar, bajra, maize (fields), orchards, tea gardens, they all have leopards."

"It's just they are so secretive. And all they need is 52 dogs a year."

It's not just leopards, she insists. "There are jackals, foxes, wolves, hyenas -- all living outside protected forests, in human use areas. There are also a lot of herbivores, but they are rarer because people hunt them and dogs don't let them be."

"India has one of the highest livestock densities in the world, and stray dogs. For leopards, that's great. There are tigers living in the Brahmapuri landscape (near Nagpur). Gir (in Gujarat) is around 2,000 sq km while the lions are occupying 10,000 sq km, even village lands outside."

The density of people has not much to do with how much wildlife there is, she says.

"We as ecologists look at ecological carrying capacity -- how much resources the animal needs. But there's also something called sociological carrying capacity -- whether the people will allow them to remain or not. For India, that is very relevant."

In a fascinating BBC documentary, Leopards: 21st Century Cats, noted conservationist Romulus Whitaker makes the same point: That India's culture and ethos have helped wildlife survive; that leopards live in thickly human populated areas and do not attack unless messed with.

Whitaker, who is to India's snakes what Dr Salim Ali was to birds, features Athreya in the documentary, which has not been shown in India, but which you can find on the Internet.

Please click NEXT for more...</p

"If you look at the Western way of handling conflicts, it is only about removing the animals," Athreya says. "If they are coming for livestock, you kill them or you translocate them."

That model, she says, cannot work for a country with 1.2 billion people.

Relocating a leopard will have problems in the area from where the animal is captured -- where new leopards will move in -- as well as where the animal is released. Resident animals known their area, the people, and avoid them. A new animal doesn't, so conflicts can happen.

Meanwhile, where the leopard is released, the stressed and traumatised animal either starts towards home -- like Ajoba -- or attacks whatever it can find. And in a country like India, running into people in both cases is inevitable.

"A lot of problem areas are the release sites of leopards," Athreya says.

For instance, leopards caught in Gujarat's farmlands are released in the Gir area, where government data says 60 attacks have happened in 2012.

Similarly, Gorumara in West Bengal, where cats caught in tea gardens are released, has a leopard problem.

Around the Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra, where leopards caught from the Nagpur area are released, is another problem zone.

In the Sanjay Gandhi National Park around Mumbai, at the peak of translocation in May 2004, 19 people were attacked. At that time, Athreya says, "It was thought to be a leopard forest, so (the thinking was) any leopards from anywhere will be happy in the leopard forest. It still happens with other animals -- barn owls caught from South Bombay are released there whereas that (South Bombay) is their home!"

After her studies found leopards living in sugarcane fields next to people way more peacefully than expected, "there was a lot of interaction with the forest department. And the officers were also good at many levels."

After translocation to (from other areas, and adjoining Mumbai suburbs) the Sanjay Gandhi National Park was stopped, Athreya points out, "between 2006 and July 2012 there was not a single confirmed human death due to leopards. There is a much bigger awareness now in this state."

The boundaries of administrative divisions, she says, are where attacks occur. Because that's where caught animals are released, hoping they will go someplace else.

Please click NEXT for more...</p

"Ajoba was caught in the Ahmednagar division after he fell into a well chasing a dog; he was left on the edge of the Thane division," she points out. "It was March-April, really hot. The poor guy was travelling. He must have been really tired. The vet, she is a tiny little girl of 5 feet, Karabi Deka, tranquillised him. And as we both looked at him, he seemed like a gentle old leopard. So we named him Ajoba."

Athreya collared five other leopards -- including a male, Jai Maharashtra, and two females, Sita and Lakshai -- and a tigress near Nagpur. Data from their collars defied set notions.

The tigress lived only outside protected forests, in croplands and small wooded patches. She never attacked people.

Sita, who was pregnant when she was collared, lived for four months near the site of release. When the cubs were big enough to move, she travelled back to where she was caught, about 60 km away.

Athreya says she knew collaring would be challenging. "The then Maharashtra chief wildlife warden insisted that I collar leopards to prove that they could indeed live close to humans without being as dangerous as one would expect."

She was reluctant, she says, because she knew the leopards live among people. "And if something (untoward) happens, it will be my animal... The permissions from the ministry came so soon that I had no choice!"

It was stressful, she says, "because these animals were living in towns, they were not even farmland leopards. But it was fascinating."

One midnight, she got a call that two leopards had pounced from the sugarcane fields on a father-son duo riding a motorcycle, bitten them in the leg, and ran away. It was near where one of the collared animals was.

Her assistant, a local farmer, dug deeper and unearthed a stunning story: A man in a jeep had had chased a leopard on the road for some time. About half an hour later, the father-son came riding by.

So one leopard was chased by a human, and two leopards attacked -- but did not kill, something they could have easily done -- two humans together!

Jai Maharashtra was drinking water in a village when some kids chased him. He ran into a house, whose occupants fled, locking the door. There was a deaf and mute person left inside. The leopard ran into the bathroom.

After the leopard was eventually captured, the villagers would not let Athreya and her team go -- they all wanted to have darshan first.

"The administration is not trained to use PR as a tool to ease conflict, but conflict issues are a lot about public relations -- as much about humans as it is about animals," Athreya says.

The people are the reason why she is "not worried about wildlife in India. "Our rural people -- they are 70 per cent of our population -- see these issues very differently than we do. They are used to living with wild and domestic animals," she says.

Please click NEXT for more...

Her study of leopards in human areas -- funded by a Norwegian government grant and the Kaplan Scholarship she won from global big cat conservation organisation Panthera -- is called Project Waghoba, after a large cat deity worshipped across western and central India (External link: www.projectwaghoba.in).

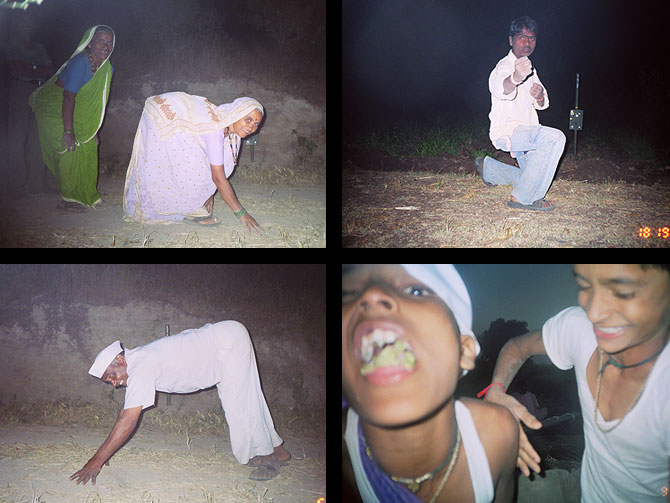

Most human-animal interactions, Athreya says, are peaceful; and laced more with humour than fear.

A woman washing utensils threw the water into the field next to her; it fell on a leopard sitting there. It growled, and she threw all the utensils and ran away. Such stories, she says, are always accompanied by guffaws by the farmers.

"99 per cent of the time the human-animal interactions are peaceful," Athreya says. "But only attacks are reported. That increases fear in the minds of the people -- who have no problems with these animals otherwise."

The problems arise, she says, when it becomes a game of power -- when wannabe politicians get into the act. And that public pressure -- at an individual level, most villagers are okay with the leopards, she says -- to "do something", she says, results in translocation, which is still on in all Indian states.

If an animal has to be caught, she says, it is best to limit contact with humans, and release it near where it is caught -- not in some forest far away.

She points out that the practice of villagers rescuing cats from wells (where they often fall into chasing dogs) -- by placing a ladder in the well or lowering a cage and letting the animal go once it is brought up -- has led to fewer attacks in Maharashtra.

Athreya is hoping the movie Ajoba will change the public perception about leopards, at least in Maharashtra, where translocation is still on, though much less than elsewhere.

Dahake, Athreya says, "is looked up to a lot because he is a budding director whose first movie was really nice. I hope Ajoba will be as sensitive as (Dahake's earlier film) Shala."

Athreya, whose cell phone caller tune is Vincent, American singer Don McLean's ode to van Gogh, and who thinks Marathi films are "much nicer than the usual unreal Bollywood movies," helped the director and his scriptwriter with research for the film.

"He's not sensationalising the issue," says Athreya. "He's bringing out the social-political-cultural aspect. The rest is his creativity, which I have no business interfering with."

Please click NEXT for more...

If leopards are harmless if not messed with, what explains Uttarakhand, where man-eating leopards continue to kill people?

"This is totally blasphemous," Athreya says, "but I often wonder -- if Jim Corbett didn't live in Uttarakhand, I don't think that problem would have happened!"

"I have the Gazetteer of 1910 of Garhwal or Pauri Garhwal. Till 1910 all the deaths in that area have been mentioned -- even due to flu and other causes. There's no single death due to leopards. The Gazetteer even mentions that leopards come to villages and take livestock. Corbett started operating in 1911. It's very interesting for me. If that man didn't exist there, would Uttarakhand have lost so many people?"

That culture of killing, she points out, has continued in Uttarakhand.

"The only way they look at it is killing (leopards); 550 people attacked by leopards in 10 years in Uttarakhand, 550 leopards killed. They kill (the supposed man-eater), and within weeks there is another human death."

"Why is that? Killing (the leopards) should have stopped it. It hasn't stopped it even in 100 years. Why isn't anyone stopping and asking that?"

In the documentary Leopards: 21st Century Cats, Whitaker features a schoolteacher in Uttarakhand's Chamoli district, Lakhpat Singh Rawat, who, livid with leopards killing his students, gets a government license to kill man-eaters and has killed 43 leopards as of March.

You can see Rawat's blog (external link, and warning: Disturbing, gory images) here: https://lakhapat.blogspot.in/

"He goes, he sees the first eye-shine (light reflecting off big cats' eyes) and he kills it," Athreya says. "From my camera-trapping work, I find that two, three animals use the same route in the same time. Which animal is your man-eater? You can't say! It's difficult! And Jim Corbett used to sit on top of a tree in the moonlight. It's not even easy to say from photographs which leopard is which!"

Rawat says man-eating leopards are active near villages between 6 pm and 8 pm. "By that logic all the leopards where I work would be man-eaters," Athreya says. "But no one has died to leopard attacks where I work, even though they come close to houses in the night to hunt domestic animals."

Rawat also says 60 percent of man-eaters are female leopards. Adult females, Athreya says, almost invariably have cubs. Think of what that does to the cubs, she says.

"I'm not talking of revenge, but the fear, aggression, the trauma and how that might change the behaviour of the animals towards humans."

Please click NEXT for more...

Wild animals in most of rural India elsewhere, she says, "are interacting with humans all the time. Houses don't have walls, kids are playing near fields, kids are coming back alone from school, yet there are no predatory attacks -- there are one or two accidental attacks. But you never know what might tip it. I'm not playing the role of god to tip it."

She says she "had absolutely no problem" with the administration in her work. "In fact, a lot of times my work was really easy because of their help. The local officers were totally fascinated with my work."

So were the villagers; they peppered her with questions when she was going around collecting leopard poop for scat analysis. Her assistant once told them they would sell it to the Chinese for a lot of money!

"Nobody (except a few in the forest department) knew I had collared the leopards," she says. "I could not even go into the areas with my receiver because then people would know the leopards were there!"

Leopards in India, she says, "are moving, occupying more, newer spaces as areas are becoming irrigated and there is more farming."

In Aurangabad, she points out, there were no leopards even 20 years ago. There are now.

She believes Gurgaon and Bangalore could have leopards. Her belief was confirmed when Rediff.com could access the photograph of a leopard snapped less than 3 km from Delhi, in the Gurgaon-Faridabad-South-Delhi belt.

"These cats are so secretive that we rarely know they are there," Athreya says. "They go about like ghosts. It is important that we realise it is in our hands to decide where conflict will go. Any intervention with wild animals in human use areas has to be done very carefully."

Did you know?

•The best place to see leopards in the wild is Bera, Rajasthan. There too, they live next to people. The locals can't remember any instance of attacks.

•Tranquillising a big cat requires skill can go horribly wrong. A concoction of two chemicals has to be prepared; the strength depends on the animal's weight. After the animal is shot with an anaesthesia dart, it needs to be left alone. The more stressed it is, the less effect the tranquilliser will have.

•Leopards have been recently radio-collared in Jammu and Kashmir. And two have been collared and released in Maharashtra as well.

•As tiger conservation laws get stricter, leopards are increasingly being targeted by poachers. The demand for leopard body parts comes from the same source as tiger parts: Chinese medicine.

•Keeping villages and towns clean -- thereby reducing stray dogs and pigs, prey for leopards -- can keep leopards away.

Please click NEXT for more...

...