For Vaihayasi Pande Daniel, the granddaughter of a freedom-fighter, Jallianwala Bagh is the most important pilgrimage. The spot where 94 years ago, more than 1,000 people were killed in cold blood, was a must-do on her life's itinerary, she writes after a recent visit to the hallowed garden

When Sir Michael Francis O'Dwyer was suddenly assassinated by Sikh revolutionary Udham Singh at Caxton Hall, London, in 1940, 21 long years after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, headlines in British newspapers (see image) attributed it merely to the former's connection with the 'riots' in Amritsar when he was governor of Punjab.

But then, 'riots' was always a convenient catchall term for anything those strange natives were discontentedly rumbling and unnecessarily hatching conspiracies about, during the days of British Raj.

Singh said at his trial, ringingly: "I did it because I had a grudge against him. He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him. For full 21 years, I have been trying to wreak vengeance. I am happy that I have done the job. I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty. What greater honour could be bestowed on me than death for the sake of my motherland?"

Neither his statement, nor trial at which he was meted out the death penalty, opened up any hindsight/revisions -- let us not even venture to say remorse -- into the way Britain looked back at a 10-minute long cold-blooded massacre of 1,000 people (1,500 were injured), including women and children, at the hands of 50 riflemen and 1,650 rounds of ammunition directed at an unarmed crowd on April 13, at the Bagh. The riflemen were under the command of Brigadier General Reginald Dyer (who reported to Sir Michael O' Dwyer and who in turn approved of all of Dyer's actions).

People go to Tirupati on pilgrimage. Or to Varanasi and Mathura.

But for the granddaughter of a freedom-fighter, Jallianwala Bagh is a much more important pilgrimage.

Hardly two years after Udham Singh shot O'Dwyer, and a day after Mahatma Gandhi's call for civil disobedience in Bombay, Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and some 360 Congress protestors and leaders across India were arrested on August 9, without trial, to spend nearly the rest of World War II in jail. My grandfather, Sheo Sharan Pande, based in the sleepy town of Khandwa in Central Provinces and Berar, was one of them.

It was a shrewd strategy to keep the troublemakers locked away and quiet, as arrests mounted, while Britain concentrated on waging war with Japan, Germany and other Axis powers, and it totally changed the course of my family's life.

My father, who was 15, and grandmother were suddenly left alone, bereft of the only earning member of the family (my uncle was away in college). They had no idea where the police had taken my grandfather. There was simply no news. There were only rumours circulating, as the Quit India Movement became a conflagration and took a violent shape and the English became panicky -- also because they were losing badly the war in Burma (and in Europe) at the time. One rumour was that my grandfather and several others were being sent to Africa.

Finally after three weeks my grandmother received a secret message from a sub-divisional officer family friend that she could see her husband if went at about 2 am to the Khandwa railway station. At a siding there, a coach would be standing and her husband would be brought there. My grandmother was sworn to secrecy. My father accompanied my poor grandmother there, where they met my grandfather; the police didn't object.

Either then or a little later they learned that he had been taken to the Nagpur Central Jail. They were not officially informed of this. No correspondence was allowed for several months. They faced great financial problems and friends, well-wishers and family would secretly slip them money to survive.

So a visit to Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar was a must-do on my life's itinerary...

Please ...

The silent historical garden, a short stroll from the Golden Temple, is a dignified, poignant memorial to those who suffered hideously for attending a public meeting on Baisakhi day 94 years ago.

Theirs was the kind of peaceful protest that my own grandfather participated in, and sometimes led, in Khandwa -- prabhat pheris that ended with the Congress flag being unfurled and the singing of Vande Mataram in the park across from his home.

Luckily he was not shot for it.

The massacre at Jallianwala Bagh played an important role in my father's formative years. The ghosts of those massacred haunted all right-minded Indians growing up in those days of British tyranny. As a boy, my grandmother had early on told him the facts of Jallianwala and about Bhagat Singh. She would sing him Mastana Bhagat Singh as a lullaby to him. He was brought up fearing and hating the unjust, red-faced 'Tommies' (soldiers and officers) for the violence they were suddenly capable of. My grandfather's home was always abuzz with visitors and with talk about how to get rid of the British. Says my father, "Jallianwala massacre was, of course, a most provocative issue."

A little background on the situation in Amritsar and Punjab in the run-up to the Jallianwala massacre (as per details available at the museum at the bagh and London's National Army Museum, Strobe Talbott's Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy, and the Bomb and Wikipedia): A few days prior to the carnage, a crowd had demonstrated outside the town's deputy commissioner's office for the release of arrested local Independence movement leaders Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who were arrested April 10 for protesting the imposition of the foul Rowlatt Act. The crowd was shot at, a few protestors killed, the situation escalated and over the following days riots broke out.

A British Church of England missionary named Marcella Sherwood, traveling on a bicycle, was caught in the mob violence April 11, in a tiny lane called Kucha Kurrichhan, while taking Indian schoolchildren to safety. Though she was rescued by the locals, including the father of a pupil, it was not before she had been beaten, kicked and severely injured.

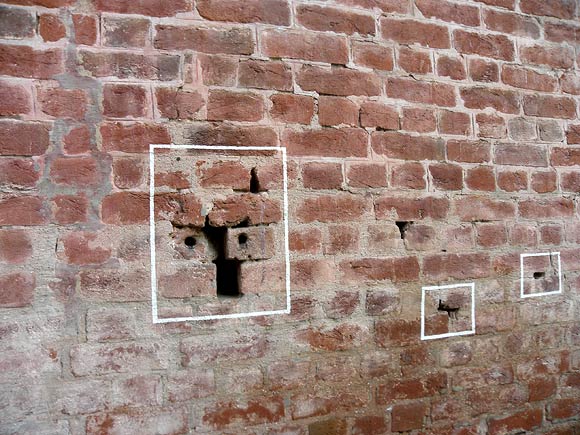

The Sherwood incident infuriated local commander Reginald Dyer. He issued an order that any Indian using Kucha Kurrichhan lane in future needed to crawl (See this photograph) and an Indian coming within a lathi's length of a British policeman would be whipped. Whipping posts were constructed in the middle of Amritsar.

Please ...

Dyer's order, quite obviously, upset all of Punjab. Though Amritsar was quiet, violence racked the rest of the province and martial law was clamped down, preventing public gatherings of more than four people.

Thousands arrived in Amritsar for the Sikh festival of Baisakhi and gathered at Jallianwala Bagh, a public garden for the festival; some for the purpose of a protest meeting. The gardens were milling with around 20,000 – many were villagers who did not know about the new rule against public gatherings -- and there was much discussion in the gardens about Dyer's cruel orders.

An hour after the meeting began, at 4.30 pm, the stern, moustachioed Dyer arrived at the bagh with his 90 soldiers and ordered the dreadful killing spree to start.

Dyer asked his soldiers to not fire in the air and to even shoot at people who had collapsed.

The horror then began to unfold.

Terrified crowds began stampeding towards the exits. The wounded lay in heaps, trampled and shot at again and again. Blood soaked the ground. Screaming, moaning and terrible sobs rent the air.

In minutes a serene green garden was transformed into a pitiless purgatory.

I entered the garden through the main entrance – probably the route Dyer and his soldiers used. It is just a narrow four- or five- foot passage between buildings that nearly elbow each other. One cannot imagine how thousands could have hot-footed it out of here, escaping the hail of bullets that day. And the bagh had just three or four other exits, even more narrow.

Please

The narrow alley opens out into the garden that is surrounded by buildings on all sides. The garden, planted with beautiful flowers and shrubbery, spreads across a few acres and is tastefully dotted with spots and a small museum that recreate how history unfolded that hot day in April.

In the museum, among various archives of photos and letters, there's a large and impressive mural of the massacre. And a moving first person account from a victim's wife.

Please ...

There is also an anguished, but elegantly written letter, from Rabindranath Tagore to Lord Chelmsford, returning his knighthood, that all Indians must read:

Your Excellency,

The enormity of the measures taken by the Government in the Punjab for quelling some local disturbances has, with a rude shock, revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India. The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments, barring some conspicuous exceptions, recent and remote.

Considering that such treatment has been meted out to a population, disarmed and resourceless, by a power which has the most terribly efficient organisation for destruction of human lives, we must strongly assert that it can claim no political expediency, far less moral justification. The accounts of the insults and sufferings by our brothers in Punjab have trickled through the gagged silence, reaching every corner of India, and the universal agony of indignation roused in the hearts of our people has been ignored by our rulers- possibly congratulating themselves for imparting what they imagine as salutary lessons.

This callousness has been praised by most of the Anglo-Indian papers, which have in some cases gone to the brutal length of making fun of our sufferings, without receiving the least check from the same authority, relentlessly careful in something every cry of pain of judgment from the organs representing the sufferers. Knowing that our appeals have been in vain and that the passion of vengeance is building the noble vision of statesmanship in out Government, which could so easily afford to be magnanimous, as befitting its physical strength and normal tradition, the very least that I can do for my country is to take all consequences upon myself in giving voice to the protest of the millions of my countrymen, surprised into a dumb anguish of terror.

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.

And these are the reasons which have compelled me to ask Your Excellency, with due reference and regret, to relieve me of my title of knighthood, which I had the honour to accept from His Majesty the King at the hands of your predecessor, for whose nobleness of heart I still entertain great admiration. Yours faithfully,

Yours faithfully,

Rabindranath Tagore

Calcutta, May 30, 1919

Please ...

A look at the bullet-pocked, five-feet wall of the garden, from where so many tried to climb up and escape, but were shot at... or a peer into the martyrs' well, where hundreds jumped to escape the bullets but drowned, thoroughly recollects this installment of Indian history – effectively rendering it back to life.

We have all studied/read about the horrors of Jallianwala Bagh. Yet bald details of a historical event do not successfully take you on a passage back in time. It takes a visit to ground zero to absorb and form real empathy for the victims of an event. And to remember that they died for us, for our Independence and for the life we comfortably live out today.

Those of us who grew up in a more prosperous post-Independence India cannot understand how utterly racist and bigoted our erstwhile British rulers were. Or how damaging their 200-year-long yoke was for our land. Indians were subjugated, merely on the basis of racism (that was as stunningly horrific as Hitler's master race scheme) to the rule of whites, who felt themselves more civilised merely for the colour of their skin.

Jallianwala Bagh is a killing field as representative of the scar the British inflicted on India, as say Auschwitz concentration camp, Poland, is of the scar the Germans inflicted on Jews, gypsies, communists and gays.

The British actions after the massacre is certainly testimony to that. The facts of the tragedy were not heard of in England till December 1919! According to Tim Coates's The Amritsar Massacre, 1919: General Dyer in the Punjab, Dwyer telegraphed this message to Dyer: Your action is correct. Lieutenant Governor approves. Dyer continued to terrorise Amritsar even after the massacre, issuing even stronger edicts.

Official British death figures were entered as 379 when in reality the figures were shockingly higher.

Edwin Montagu, secretary of state for India, ordered Dyer, in late 1919, to appear before the specially convened Hunter Commission. When Dyer was questioned about his actions, he said had he gone to Jallianwala Bagh and peacefully dispersed the crowd, the people would have laughed at him and he would have thought of himself as a fool. He said instead of 50 riflemen he would have preferred to have brought machine guns mounted on armoured cars, but the entrance to the garden was not wide enough. He felt he had to continue to shoot at the crowd till they dispersed and that a few shots to make them disperse would not have worked.

Dyer did not believe he needed to have the wounded attended to. He astonishingly declared: 'Certainly not. It was not my job. Hospitals were open and they could have gone there.'

The Commission did not take disciplinary action against Dyer but he was subsequently taken off duty.

But he returned to Britain a conquering hero and not as the Butcher of Amritsar. He was considered the man who had prevented a revolution. Conservative, pro-Empire British daily The Morning Post organised a collection of 26,000 pounds for Dyer and it was presented to him by a committee of women, along with a sword, for being the Saviour of the Punjab and the Man who Saved India.

No event galvanised India's freedom movement more than the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. It finally made Indians realise that their rulers were both barbaric and dangerous and their notions of justice did not apply beyond themselves.

The monstrous event that occurred in a quiet garden in Punjab, inexorably, put us on the road towards that red letter day in 1947 when India bravely attained her freedom. It was also a special day for my family: my grandfather unfurled, in a public ceremony, for the first time, India's flag atop Khandwa's town hall at 9 am, August 15, 1947 and gave a speech.

Ninety-four years after the massacre, Jallianwala Bagh remains the ultimate pilgrimage spot for nationalist Indians.