American civil rights attorney Asim Ghafoor tells P Rajendran/Rediff.com why he may have become a target of NSA surveillance.

When Asim Ghafoor, a civil rights attorney who has often argued for clients like the Saudi and Sudanese governments, found that he was under the United States government's surveillance -- again -- he could not believe it.

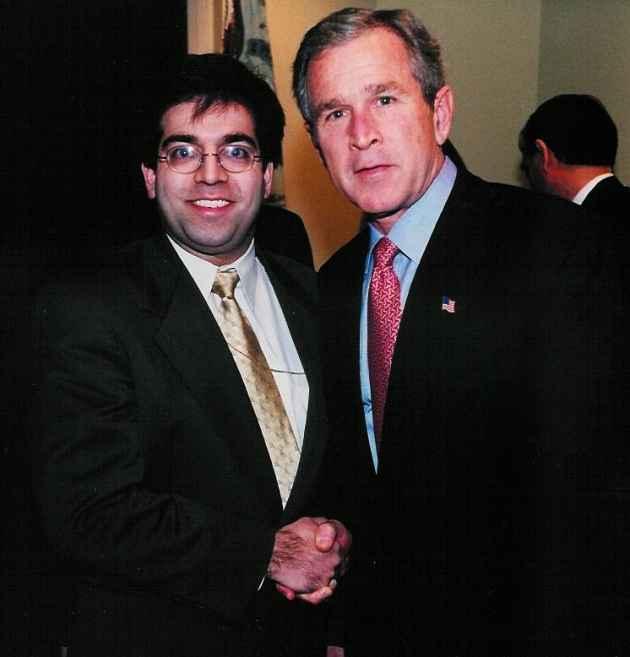

Ghafoor, who was born in St Louis, Missouri, but whose parents came from India, has been named by The Intercept journalists Glenn Greenwald and Murtaza Hussain in their latest piece based on the revelations of Edward Snowden, the National Security Administration employee now living in Russia.

Of the 7,485 people in the excel sheet Snowden gave them, the journalists named four others: Ghafoor's old partner Faisal Gill, a Republican Party member who ran for Viriginia's House of Representatives and worked for the Department of Homeland Security under President George W Bush; Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, America's largest Muslim civil liberties organisation; Hooshang Amirahmadi, an Iranian-American professor at Rutgers University of international economic development and planning; and, finally, Agha Saeed, the national chairman of the American Muslim Alliance and a former professor at California State University. Most of the other names were Muslim, the journalists have said.

In 2004, Ghafoor and another lawyer, Wendell Belew, discovered they were wiretapped as part of a US government investigation of their client, al-Haramain, an Islamic charity suspected of having ties to terrorists.

After the group and its lawyers sued the government in 2006, US District Court Judge Vaughn Walker ruled in their favor. The appeals court reversed the penalties without rejecting the argument that the defendants' rights had been violated.

What Ghafoor did not know then was that since March 9, 2005 the NSA had already been independently monitoring his e-mails, and this not just as part of surveillance of people he dealt with. That he learned last month from journalists at The Intercept called him to verify his e-mail.

Ghafoor, a practicing Muslim, had supported the Bush government in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. He says that was because Al Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden's role in the attack had been established but the Taliban, then in power in Afghanistan, would not hand him over to the US.

Though he was born in America, his family had spent a year each in Saudi Arabia and Hyderabad as his father sought work. After his father Mohammed Abdul Ghafoor died in a plane crash in 1980, his mother Sara waited for a year for her children's school to be over before moving to Texas.

Ghafoor went to school, college and law school there. After earning his Juris Doctor from the University of Texas at Austin he became a legislative assistant to then Congressman Ciro D Rodriguez (Democrat, Texas). Ghafoor says went into private practice after becoming a licensed attorney in 1999 and because he and his wife Ebtehaj now had a child on the way.

Please click NEXT to read the interview...

As political director of the Islamic Institute, you backed the Bush administration's plan to attack Afghanistan after 9/11.

Yeah, I remember that. Right. Mm-hmm.

What changed for you after that?

That's a good question. I was against the first Gulf war in 1990. (But this time) when the US government had decided -- or had evidence that -- Osama bin Laden was involved with 9/11, (and that) the Taliban (which) was controlling Afghanistan was refusing to turn him over ... I was in support -- along with a majority of Americans -- that, rather than outright invasion, maybe a limited airstrike or an attack -- not like 1998, when (President Bill) Clinton sent Cruise missiles there but more of a mission to kill or capture Osama bin Laden -- was in order.

I was in support of that -- and it was a mistake. It became a costly, long, unwanted war with unwanted consequences.

The NSA has said that representing a foreign government legally does not make an American lawyer a foreign agent. As you see it, does that hold true in real terms?

Yes, absolutely. There are hundreds of lawyers who represent foreign governments. None of them are surveyed. I'm the only one.

In the earlier case you dealt with, your fellow lawyer Wendell Belew also came under surveillance, right?

There is one slight difference. Wendell and I and other people who worked with us were not the targets of the surveillance. The targets were the foreign nationals who we were representing.

When we saw the summaries of the surveillance (which the Federal Bureau of Investigations had inadvertently given to the al-Haramain representatives), our names, our e-mail address, our phone numbers -- nothing was there. And we saw the un-redacted classified documents. We weren't identified at all. We figured out who we were based on the context. (But) we were not under surveillance.

This (NSA surveillance he learned of from The Intercept staff) is very different. What happened, according to Glenn Greenwald and the Edward Snowden documents is that the US government went to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court and sought surveillance of my e-mails along with 7,000 other (people's). That's very different. That's not (like when) we've (done work) with the Saudis or the Sudanese...

But does that too not involve lawyer-client confidentiality issues?

Which is what I told Greenwald's colleagues at The Intercept: The US government's agents or lawyers who prepared this paperwork to get this information should have known that they cannot use this information. Unless they saw some ongoing criminal activity they cannot take the conversation I am having with my client and use it (in court). The judge would just throw that evidence out. So they really had no basis to ask for it or use it.

Please click NEXT to read the interview...

When you grew up, what did you learn about balancing religious and legal dictates?

My family (consisted of) practicing Muslims who believed that I should pray and fast and follow the dictates of my religion. But I was never taught or instilled with anything beyond (that, such as) establishing Sharia law in America or painting the Capitol green or chopping people's hands off for crimes.

When did you find out that the government was monitoring you again?

I got a call from an editor at The Intercept saying, 'Are you Asim Ghafoor? Do you have this ...yahoo (e-mail) address?' I said, yeah. 'Are you an attorney in DC?' I said yeah. He said, 'Well, we have information from Edward Snowden's disclosures that you've been (monitored). Would you be willing to talk to our reporters?

How did you react to that?

I was shocked. I was like, not again! They said, 'You were (monitored) from March 2005 until late 2008 and maybe beyond that. We don't know.' That was unbelievable. This is why I was suing the government -- and winning against the government. How dare they (do this)? I was offended.

Could you tell us something about your discussions with Greenwald and Hussain? You decided to allow your name to be put out there, right? As Greenwald wrote on reddit, 'All five of the people we named here consented to their inclusion in the story.'

Oh, no, no, no. They were going to put it out anyway. It was not my decision. They would have run it. They had an agenda and I respect it -- (asserting) that people are targeted for their political beliefs, for their political associations, for their religion. And they identified myself, Faisal Gill, the professor at Rutgers (garbled). I don't want this story. I had no interest in having it published. I don't want to put my family through all that. Yeah. No way. I told them that.

Please click NEXT to read the interview...

The impression I got from the reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything chat session) is that they kept out most of the names because they didn't want to put all the e-mail addresses out there, that they contacted you and asked you and that's how you came into the picture.

Oh yeah, they told me they're doing the story and do I want to (give) my side of the story. But they didn't ask me anything (involving permission). They didn't ask my permission; they just wanted my cooperation. They would have pieces on me on the Internet ... Terrorist lawyer. So I wanted to co-operate to make sure that this story got everything correct about me.

Given where you work -- in Washington, DC -- how do you think Snowden's revelations are going to change the way surveillance is conducted -- for better or for worse?

Oh, so far I think it's been a positive. The mistake that Wikileaks (which had put out classified material earlier) made was that they put everything out there and they opened themselves up to... accusations that they were endangering American lives, (revealing) the names of American contractors in Afghanistan or... (the names of) those who were targets for killing.

Snowden's documents -- until now -- have not been put online for searching. They've been analysed by the three teams of journalists who were given the documents and the information has been selectively put out.

If you recall the first revelations, about what they call the metadata -- the vacuuming up of all the information (in) section 215 -- that caused enough outrage on Capitol Hill where Congress is about to make that activity illegal. The House (of Representatives) has passed a version. The Senate is working on something, and the President has not objected to it...

The fact that a whistleblower's information causes Congress -- which isn't doing anything -- to actually move on something... I think that's always a good day in Washington (when that happens).

Please click NEXT to read the interview...

Many groups argue that, whatever the idealists say, the end does justify the means. What would you deem a suitable way to conduct surveillance, balancing the needs of national security, transparency and privacy. How would you do that in a democratic nation?

If you look at the history of some of the protections we have in the US -- no debtor's prison, (that) you can't just lock somebody up without reason, habeas corpus, warrants. These things have been around since before America was founded. It may not have been written in Runnymeade and (included in) the Magna Carta (which limited the British king's power). But the element of protection from an overzealous government has been enshrined in US law.

My response is that we have these processes for a reason. We don't torture people here because we want to protect our troops when they're overseas -- to protect them from being tortured. We don't break into people's houses and look at what they're doing because when somebody else (wants to) we don't want them breaking into our house and looking into our personal affairs.

There was a time when I was growing up -- when I was a teenager in the seventies and eighties in the US -- where people caught red-handed with drugs, contraband, stolen material, would walk free from jail because of some technicality. Oh, they (the police) didn't have the warrants (garbled), the jury instructions were read three times instead of only one time... On technicalities, guilty people caught red-handed were walking free.

The American people, at some point, said let's slow this stuff down. Now Miranda warnings out the window. If they think there's an ongoing crime .. no Miranda warnings. (The process is delayed) for days, months... We're always having this discussion about a balance.

To me, getting rid of warrants or having such a flimsy warrant procedure is not a good balance. The type of thing a warrant forces a government to think about -- the court, anticipating a judge's questions -- are very important part of our process. It makes anybody who works in government think twice, three times, four times, ten times! Before they ask for something.

What about a secret warrant as in the FISA court?

They are very distinguished judges who I appear before in court who rule on these things. But they're not given the benefit of a staff, they're not given any other opinion because it's one-sided by its very nature, and they're scared. They're not personally scared. They're frightened into acting in certain ways, which in normal circumstances they would not.

For example, if an agent says, 'Your honor, we need this warrant. If we don't listen to this guy Capitol Hill will be enshrouded in a mushroom cloud. Oh, by the way, you can see Capitol Hill outside your window.'

I mean, what's the judge going to do? They'll rubberstamp it. Why not? I would!

I don't know enough about that process. I wish I did. To me, the checks and balances ... are not so great. When the President released some of the memos, I was not impressed with the rationale. I think (the judges are) too quick to approve these (warrants). They've only denied, I believe, a dozen out of thousands of applications.... In any county court, state court you go, I don't think you have a 99 percent approval rating on warrants.