While WHO efforts have dramatically reduced leprosy, India still accounts for more than half of the world’s new cases each year.

Dr Jonathan Reisman, who spent four months in Kolkata with patients who have become socio-medical outcasts, attempts to fight the much-misunderstood disease

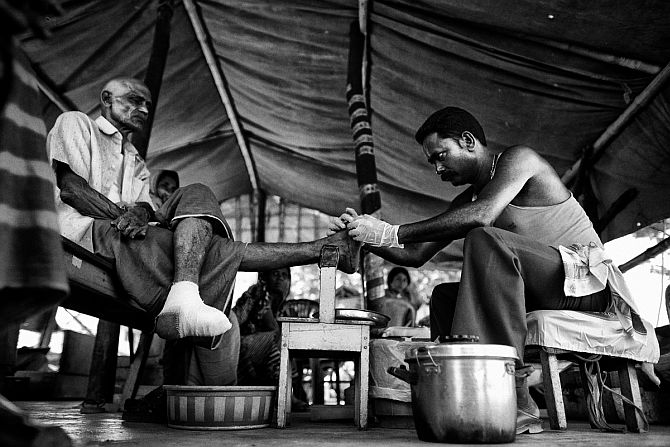

On a scorching dry day in May, wind blows off of Kolkata’s HooghlyRiver and through a makeshift medical clinic on the river’s sandy banks.

Abdul sits among 25 patients under a bamboo-and-tarp roof rubbing Vaseline into his deformed and crumpled hands.

This is Chitpur -- a leprosy clinic run by the charity Calcutta Rescue.

On the industrial fringes of the city, Abdul and over 300 other leprosy patients have found a refuge both from the hot sun and from the society that rejects them because of their illness.

The stigma that leprosy has carried for millennia remains strong in large swaths of Indian society today. More so than even the Dalits of the caste system, this disease epitomizes the repulsive and the outcast.

On this hot afternoon, Abdul and others wait at Chitpur for a cleaning-up of their chronic foot wounds and a regular doctor’s check-up.

Abdul, now 55, grew up in a small slum not far from here with his parents and brother.

At age 16, he noticed pale spots on his arms and chest. Knowing it could be leprosy, his first thought was to hide the spots from everyone, including his family.

...

His parents eventually noticed and took him to the local homeopathic doctor. The homeopath immediately and correctly diagnosed leprosy, having found that Abdul’s sense of fine touch was decreased within these pale skin patches.

This occurs because the leprosy bacterium grows in, and destroys, the nerves that create the sense of touch.

Over the next three years, his family spent much of their money on weekly homeopathic treatments. However, the disease persisted and continued its destruction of Abdul’s body over the ensuing decades.

With the deformity that followed, Abdul experienced firsthand the social rejection that leprosy brings. And it is precisely this social stigma of the disease that constitutes a major barrier to the virtual elimination of leprosy in India.

Often people see the initial skin rash of leprosy and do not ‘come out’ and seek medical help, which they often do not know exists.

As a result many do not receive treatment early enough to prevent irreversible deformities.

At that time, in the 1970s, therapy with the antibiotic dapsone was available, however Abdul never got it in time.

Years later, when leprosy started to destroy nerves and whittle away at his face and limbs, he faced both a crippling disease and lifelong estrangement from society.

...

The international medical community attempted to distance this disease from its ancient baggage by changing the condition’s name from leprosy to Hansen’s Disease in the early 1900s.

Yet today many in India believe that leprosy is a curse from the gods, that it is untreatable, and that it is highly contagious.

Abdul first experienced the stigma when his parents tried to arrange a marriage for him with a local girl.

The girl’s family had heard through local gossip that he was visiting the homeopath for leprosy. When he went with his parents for an introductory visit, the girl’s family saw the pale patches on his arms and chased them out of the house.

Abdul was emotionally crushed by this experience. He felt at that time as if a whole sphere of human experience, of love and relationship, was closed to him as a result of his disease. He would never marry.

He began to isolate himself. He quit his job at the local grocer’s shop and stopped going to school just short of finishing the 10th grade. He refused to leave his house for days at a time. One of his teachers sought him out at home and pleaded with him to finish his education, but he never went back.

His physical disfigurement increased in step with his social isolation as the years went on.

Today treatment for leprosy has progressed and highly effective multidrug therapy cures virtually everyone.

...

Since 1995, the World Health Organization has made MDT available for free throughout India. As a result the number of new cases in the country has decreased dramatically, going from roughly 456,000 in 1993 to roughly 130,000 in 2009.

While WHO efforts have eliminated leprosy in 119 out of 122 countries, India still accounts for more than half of the world’s new leprosy cases each year. Thousands of victims do not know about available therapy or how to acquire it and hide their disease for too long.

In India’s intensely traditional society, stigmas do not die easily, but with a persistent and organised effort, focused on getting early treatment to those who need it, this disease can be turned into a harmless rash.

Getting the message out is not as simple as roaming through poor Kolkata neighbourhoods with a megaphone calling all lepers by loudly describing the skin signs of the disease.

Calcutta Rescue tried this and failed to uncover a single new case of leprosy.

People from those same neighbourhoods were appearing at more distant clinics and being diagnosed with leprosy. CR understood that for the people of these poor neighbourhoods, asking for help can sometimes be tantamount to public declaration of their disease; its strategy was ineffective because of the disease’s stigma.

Leprosy grows in the cooler parts of the body, mainly in superficial nerves of the face, arms and legs.

Just as in diabetes, nerve damage from leprosy results in loss of sensation and weakening muscles. Without a sense of pain to warn away from injury, miniscule traumas from sharp or hot objects happen hundreds of times each day.

Activities like cooking and walking become more dangerous and feet usually bear much of the brunt of daily life, especially in India where the poor commonly walk barefoot through the city.

...

Injury leads to chronic wounds, infection, and a cycle of tissue damage, and infection may not even be noticed because of the lack of sensation. Instead a noxious smell often announces the presence of infection and rot.

All of these forces synergistically began to whittle down Abdul’s fingers and toes, and then hands and feet.

His hands slowly became curled and fixed into rigid claws due to leprosy destroying the ulnar nerve, also known as the ‘funny bone’ as it passes the elbow.

As the nerve stops working, some hand muscles weaken while others suddenly have no counterbalance to hold the digits in their normal resting place. As a result the fingers are pulled into a permanent claw.

Abdul recalls feeling the initial unbalanced tugging on his fingers as a teenager. He lay awake at night straightening and curling his fingers, playing with this new sensation that would soon turn his hands into useless claws. Decreased dexterity leads to more micro-traumas to the hands and more whittling away and deformity.

Similar nerve damage in the leg causes Abdul to walk with a lurching gait -- for each step he throws his leg forward in an exaggerated spasm-like motion, creating more falls and injuries.

On his face leprosy has obliterated his eyebrows and weakened the muscles that close his eye.

Unable to protect the eye by blinking, Abdul and many others at Chitpur have become blind in one eye due to chronic dryness and damage to the cornea.

Abdul compensates and protects his eyes by, every 10 seconds or so, exaggeratedly scrunching up his whole face in order to close his eyelids.

Of course this loss of sight also leads to more injuries.

...

The self-perpetuating cycle of deformity and disability affects every aspect of daily life, from bathing to washing clothes to walking to cooking.

These activities grew more difficult, and Abdul grew more frustrated, isolated, and depressed as his grip strength and coordination diminished.

Abdul first received help from CR at the age of 36, 20 years after those pale skin spots first appeared. It was not leprosy that brought him to CR; this had already become an immutable fact of life for him.

It was because of a high fever and chills that he came to CR’s free clinic in Middletown Row, one of Kolkata’s poorest neighbourhoods.

It is common both in Kolkata and in the developed world, for patients with undiagnosed chronic diseases to finally get medical help only when something more acute appears on top of that long-term illness.

Abdul received free treatment for malaria, and was referred to the local government hospital where he would receive his free six-month course of MDT.

When CR’s doctors and staff met Abdul, in 1994, the charity had been operating on Kolkata’s streets for 15 years.

...

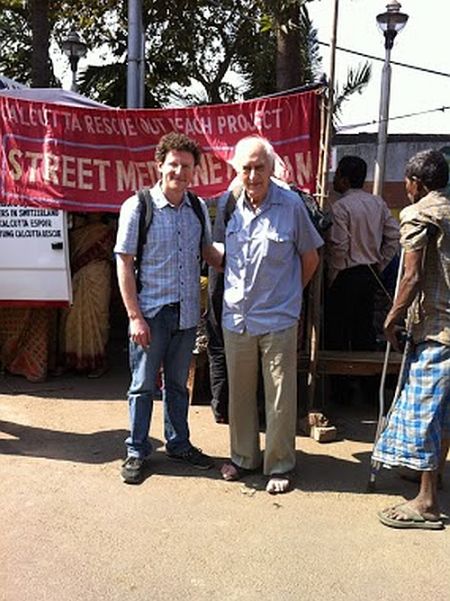

The group was founded by Jack Preger, a British doctor trained in Ireland, who has dedicated his life to serving the poor.

He first came to Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, in 1972 during that country’s Liberation War.

Preger heard a call on the radio for volunteer doctors to work in refugee camps in what would amount to one of the largest refugee crises and migrations in human history.

He treated broken families living in extreme deprivation, dying regularly of malnutrition, dysentery, and other wartime diseases.

After seven years in this environment, the Bangladeshi government permanently expelled Preger from the country. He had exposed a government official’s involvement in a child-trafficking operation that abducted children from their families and sent them to Europe for adoption through a Dutch organization.

Preger moved his services just across the border into the Indian state of West Bengal, and its capital city Kolkata (then Calcutta). There, he continued providing health care to the poorest and most depraved people he found living on the streets of the city.

He even found many refugees there from the same war that had brought him to the region.

Each day he constructed a bamboo-and-tarp street clinic in Middletown Row and treated all comers; each evening he took the clinic down for the night. And thus the practice of ‘street medicine’ here was born.

He called his services ‘Calcutta Rescue’ and began accepting foreign tourists as volunteers. Over the years, financial support from Europe grew, and CR’s services expanded tremendously.

Today, CR’s health-care network treats over 50,000 people per year. Their services feature a mobile outreach clinic that visits slums and homeless communities, four permanent clinics providing primary health care, and specialty clinics treating leprosy, HIV, TB, heart disease, pre- and post-natal care, nutrition programs for malnourished children, and a clinic for children with physical and mental disabilities.

CR works in education as well, running two schools with a total of 300 children from Kolkata’s streets and slums.

The group also runs an occupational training workshop and arsenic mitigation projects in rural West Bengal.

Preger, ‘Dr Jack,’ is now 84 and continues to show his same unflagging dedication to providing health care to the underprivileged.

CR’s street clinic referred Abdul to Chitpur where he would get a different kind of therapy for leprosy.

The pharmacologic cure is just the beginning of care. The drugs prevent further destruction of the nerves, but nothing can ever repair the hands, faces, and social lives already damaged by the disease.

Abdul learned about the cause of his disease from CR, and Chitpur’s staff treated his chronic wounds by removing dead tissue, cleaning and bandaging them, and providing tetanus vaccination.

He gets general medical care, food, vitamins, clothes, shoes, and some rent money for the small slum hovel in which he sleeps.

...

Chitpur clinic also provided Abdul with special shoes designed to protect those parts of his feet that have lost feeling.

CR’s own workshop makes these shoes, thus employing and training one group of poor people to create a product needed by another group. Such well-designed pragmatic efficiencies make CR unique among non-profit organizations and makes health aid to the developing world more sustainable in the long-term.

The leprosy shoes are available in 15 styles, each padded with microcellular rubber in ways to match an individual patient’s pattern of neurological loss.

Those patients with ‘foot drop,’ in which the muscles that bring the foot up towards the shin no longer function, receive a shoe that connects the foot to the shin with a spring that keeps their toes from dragging on the ground when they walk.

Each patient at Chitpur has an individual care plan designed for his or her needs and deficiencies.

On a public health level, however, educating India’s masses and giving them access to quality health care is the true cure for this disease. Those suffering from early leprosy must get effective treatment before they follow Abdul’s path of permanent disfigurement and social isolation.

Perhaps the same sort of awareness campaign that helped destigmatize HIV/AIDS in the United States is now needed for leprosy in India. A sustained education campaign over decades, with a ribbon as a memorable symbol, helped change the way that people view HIV/AIDS.

With India’s dismal literacy rates, however, the task is more formidable. Still, as it was done for HIV, one of the newest scourges of humankind, it must be done for leprosy, one of the oldest.

Despite the tremendous help that CR gives Abdul, some scars will always remain. He still has never left his home neighborhood since confining himself there in his 20s.

He feels comfortable and safe there. He can get a shave at the local barber or shower at the local water pump, though he might face rejection now and then.

The local chai wallahs give him steaming cups of tea for free, and he can count on help from a passerby when he struggles to button his shirt or extract a cigarette from the pack in his pocket.

And Chitpur is a short bicycle-rickshaw ride away, and Abdul visits often for social as well as medical reasons.

Among Chitpur’s older patients with obvious deformities, like Abdul, there are a few completely healthy-looking patients.

One of them is Radha, a 16-year-old girl, and she represents the future of leprosy.

...

Radha received the treatment early and was left with only a small scarred patch on her thigh where the lesions of early leprosy once were. The dramatic comparison of Abdul and Radha demonstrates the advances that have been made.

If these efforts continue, today’s generation of Indians may be the very last to have to suffer medically and emotionally from this determined scourge.

If this happens, a place like Chitpur would no longer be necessary. The clinic would not need to provide people like Abdul with a safe haven, a place to receive medical and social help, a place where they can feel a part of a social unit again, even if it is a society of medical outcasts.

The peaceful silence of the clinic’s riverside location, the pleasant shade of the clinic roof, and the friendliness of staff and patients contrasts sharply with the deformities seen and painful life-stories recounted there. With the power of information and charity, the present generation can make the need for Chitpur history.

Jonathan Reisman, MD, is an internist/pediatrician at the Massachusetts General Hospital and president of the World Health and Education Network, a 501c3 charity supporting health and education efforts in India. He spent four months working with Calcutta Rescue in Kolkata where he met Abdul.

For more information or to support Calcutta Rescue’s efforts go to Worldhealthonline.org or email whenUSA@gmail.com.