Forty two years ago, December 16, the 1971 war came to an end. India won a decisive victory over Pakistan. Bangladesh was liberated.

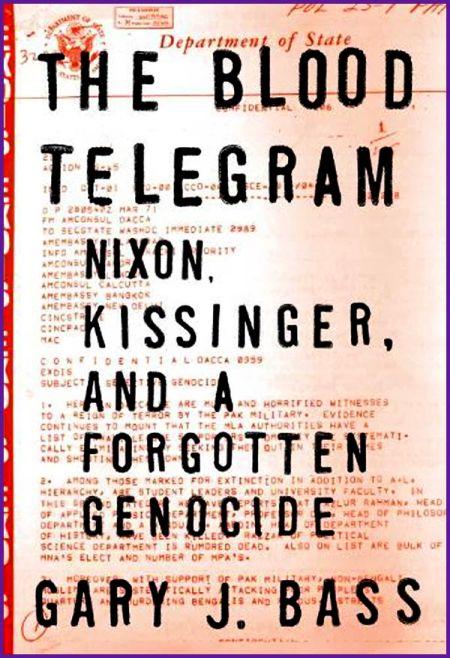

In his powerful new book, The Blood Telegram, Gary J Bass, a professor at Princeton University, has exposed how US President Richard Nixon and his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger 'allied with the killers,' the Pakistani government in then East Pakistan, as it unleashed genocide on a horrific scale.

Professor Bass discusses Nixon and Kissinger's 'moral blindness,' why they hated India and then prime minister Indira Gandhi, and their plan to draw China into the conflict in this illuminating interview with Rediff.com's Arthur J Pais.

On the night of March 25, 1971, when the Pakistan army began 'a relentless crackdown on Bengalis, all across what was then East Pakistan and is today an independent Bangladesh,' Princeton University Professor Gary J Bass writes in his The Blood Telegram, 'Untold thousands of people were shot, bombed, or burned to death in Dacca (now Dhaka) alone.'

'(Archer) Blood (the American consul) had spent that grim night on the roof of his official residence, watching as tracer bullets lit up the sky, listening to clattering machine guns and thumping tank guns,' Bass records in his disturbing book which explores material in Washington recently declassified.

'There were fires across the ramshackle city. He knew the people in the deathly darkness below. He liked them. Many of the civilians facing the bullets were professional colleagues; some were his friends,' Bass writes in his book.

Blood and his staffers thought they had to 'relay as much of this as they possibly could back to Washington.'

'Witnessing one of the worst atrocities of the Cold War, Blood's consulate documented in horrific detail the slaughter of Bengali civilians: an area the size of two dozen city blocks that had been razed by gunfire; two newspaper office buildings in ruins; thatch-roofed villages in flames; specific targeting of the Bengali Hindu minority,' Bass notes in his book.

The book with the secondary title Nixon, Kissinger and A Forgotten War has been published in America by Knopf.

'The US consulate gave detailed accounts of the killings at Dacca University, ordinarily a leafy, handsome enclave. At the wrecked campus, professors had been hauled from their homes to be gunned down,' The Blood Telegram records.

'The provost of the Hindu dormitory, a respected scholar of English, was dragged out of his residence and shot in the neck. Blood listed six other faculty members "reliably reported killed by troops," with several more possibly dead.'

'One American who had visited the campus said that students had been "mowed down" in their rooms or as they fled, with a residence hall in flames and youths being machine-gunned,' Bass writes in his well-received book.

In Washington, President Richard M Nixon and his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, with their raging dislike for India and then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, refused to support India even as millions of refugees poured into India.

'The slaughter in what is now Bangladesh stands as one of the cardinal moral challenges of recent history,' Bass writes in The Blood Telegram, 'although today it is far more familiar to South Asians than to Americans. It had a monumental impact on India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh -- almost a sixth of humanity in 1971.'

'In the dark annals of modern cruelty, it ranks as bloodier than Bosnia and by some accounts in the same rough league as Rwanda.'

'It was a defining moment for both the United States and India, where their humane principles were put to the test.'

Bass sees things in a larger perspective. 'When we think of US leaders failing the test of decency in such moments,' he muses in The Blood Telegram, 'We usually think of uncaring disengagement: Franklin Roosevelt fighting World War II without taking serious steps to try to rescue Jews from the Nazi dragnet, or Bill Clinton standing idly by during the Rwandan genocide.'

'But Pakistan's slaughter of its Bengalis in 1971 is starkly different. Here the United States was allied with the killers. The White House was actively and knowingly supporting a murderous regime at many of the most crucial moments.'

'There was no question about whether the United States should intervene; it was already intervening on behalf of a military dictatorship decimating its own people.'

'This stands as one of the worst moments of moral blindness in US foreign policy. Pakistan's crackdown on the Bengalis was not routine or small-scale killing, not something that could be dismissed as business as usual, but a colossal and systematic onslaught.'

'Midway through the bloodshed, both the Central Intelligence Agency and the State Department conservatively estimated that about two hundred thousand people had lost their lives. Many more would perish, cut down by Pakistani forces or dying in droves in miserable refugee camps,' The Blood Telegram notes.

Gary J Bass spoke to Rediff.com's Arthur J Pais over the telephone on Wednesday, December 11.

Kindly click NEXT to read the interview...

What surprised you most while researching this book?

I was surprised almost constantly while I was researching for this book.

My work as a historian is not specifically on South Asia which I think was helpful in a way. I did not come to the project with any particular pre-conceptions.

I was just trying to figure out what had actually happened.

What I was surprised was by the level of rage and emotion inside the White House in the months leading to the brutal war in East Pakistan and during the war itself.

I had expected Nixon and Kissinger to be coolly rationalising their decisions; but in fact they are remarkably angry and emotional and let personal judgments cloud a lot of their thinking.

I was surprised by the way India was sponsoring the insurgency inside East Pakistan. I did think the Indian government as a good neighbour believed in the national sovereignty of Pakistan.

But in fact what you have them (the Indians) saying is that they are talking about human rights, they are talking about genocide. In fact, they are sponsoring this massive insurgency inside of East Pakistan.

And I was surprised, lastly, by the courage of the people in the Dacca (the US) consulate. It was just physically very dangerous to be operating in the middle of this devastating military crackdown.

These American officials, especially Archer Blood, the consul, took tremendous risks. On top of that, they had real moral courage, they stick up for basic principles of human rights -- knowing that doing that is going to be very, very, bad for their careers.

And if you think about what else is happening in 1971. You think about Vietnam, right? Where there are all sorts of American officials who are refusing to pass bad news along to Washington, who are refusing to tell the truth to their superiors.

And here you have these guys in Dacca who do their job in a really honourable way. I thought it is extraordinary to see it.

I think it would be good if we remember people like Archer Blood who showed the diplomacy of the United States at its very best even as Kissinger and Nixon were shown at its worst.

There are things (in the book) that I think that may be helpful for making public policy in the future and having an American government to listen to its diplomats on the ground and listen to its experts around the world.

That I think is important -- there is a real danger of having the White House that has a politicised view of developments in some parts of the world and not being willing to listen to what its people on the ground are telling them.

In 1971, that was the Dacca consulate led by a man named Archer Blood who warned Nixon and Kissinger about the repression and the killings by Pakistani army and the genocide in East Pakistan, aimed in a great deal against the Hindus.

What would Blood have wished Washington to do?

It is an amazing story! Blood is a career foreign service officer; a very patriotic, disciplined, loyal public servant. He is not a radical within the US government; he is not looking to make some big political stand.

He is quite ambitious actually; he is looking to move up within the US government, but he is an honest reporter of what is happening at his station and he and his staff report in great detail about the military crackdown that Pakistan launches across what was then East Pakistan and is now Bangladesh starting on the night of March 25, 1971.

Blood's consulate is sending cable after cable to Washington detailing the scale of the killing; and again, more or less, dead silence.

So they try to increase the volume; the rhetoric gets louder, they start talking about genocide and still no response from Washington.

Then they finally sent in a full scale dissent cable where almost everybody from the Dacca consulate formally dissents from American foreign policy, saying we consider this policy to be morally bankrupt in the face of what the people in the Dacca consulate call genocide.

It is really an extraordinary statement; it is the first official dissent cable sent by US diplomats.

(The State Department had created the idea of having formal dissent cables in the Vietnam era at a time when there were a lot of American officials who were primarily uncomfortable with what the US was doing in Vietnam. Washington wanted to have a way in which Foreign Service officers and American diplomats in the field could formally register their protest with US government policy.

So, though that was created in the Vietnam era, it was being used for the first time in Bangladesh. Since then, dissent cables have happened over and over again.)

But this is the first one and nobody quite knows what's going to happen. Everybody in the Dacca consulate knows that signing and sending this cable will be very bad for your career, but it is only the senior officials that are really likely to face retaliation.

Nobody is going to bother going after a very junior person in the Dacca consulate. They are not big enough for retribution.

The people who really risk retribution are senior officials, the most important of them being Blood.

Kindly ...

What kind of debate did people like Blood trigger?

There is a big debate that goes on among the State Department and officials in the field, in Islamabad and Dacca and Delhi about how the US should respond to this crackdown.

Blood and also Kenneth Keating, the ambassador to India, are arguing that the United States has all sorts of leverage over the military in Pakistan.

The United States is one of the main arms suppliers, helps a lot with giving economic aid, and also securing economic aid through international financial institutions and all of this gives a lot of influence for the United States.

This is the case where Pakistan is the close US ally where Pakistan is being heavily supplied militarily by the United States. I don't think that gives the United States unlimited leverage, but certainly the prospect of economic sanctions, military sanctions, those might well have changed the minds of people in Islamabad.

What is so strange about Nixon and Kissinger is that these are people who ordinarily are masters at using leverage and are very explicit about the ways they would like to use leverage over foreign governments.

They talk about this and they say nobody ever does anything for us because we are nice. People do stuff for us because we use leverage. But in this case, they make a conscious decision not to see what their leverage could do.

I am sure there were limits to American leverage, but Nixon and Kissinger never even explored what those limits might have been.

Blood paid a heavy price for his honesty. Didn't he?

His career was really badly damaged by this. He goes from being consul general to a huge territory, not yet a country (then East Pakistan) with 75 million people -- a major post -- to being thrown at a desk job in the State Department.

Kissinger goes from being National Security Adviser to also being Secretary of State.

Blood's career is stalled and finally he winds up leaving the State Department. He doesn't get to try and re-launch his career until much later. He tries to restart it in the Carter administration. But then, he is older, there is not much he can do.

He really pays a considerable price for this dissent.

Why did Kissinger and Nixon not listen to their diplomats? There is also an argument that Nixon advances -- that 'We did not interfere in Nigeria during the civil war which caused many more deaths'.

It is interesting because as a presidential candidate he actually seems to have been at least somewhat troubled by what happened when Biafra tried to secede from Nigeria; and the Nigerian government crushed the rebellion in Biafra. So, that is sort of historically interesting.

As an argument it doesn't really work logically and to say that I did the wrong thing or therefore I should do the wrong thing again.

So, it makes logical sense if you really believe that something really should have been done to help people in Biafra, then it doesn't follow from that that therefore you should do nothing now for people in East Pakistan.

I think Biafra is not a major factor in their decisions. I think the bigger factors are, first of all, the Cold War context of India being officially not aligned, but seeming to a lot of US presidents, not just Nixon, to be leaning heavily towards the Soviet Union.

You also have the role that Pakistan is playing in helping with America building bridges to China.

Beyond that, you do have, I think, the personal feelings of Nixon and Kissinger where Nixon, in particular, has a pretty deep contempt for India and for Indians.

How did the contempt for India happen, first, in the case of Nixon and then, in the case of Kissinger?

Nixon, he prided himself on knowing a lot about the world and travelling a lot. And, on some of his early trips to South Asia, he felt personally condescended to first by Jawaharlal Nehru and then by Indira Gandhi and that kind of left a bad taste in his mouth.

He was treated very well by the Pakistani generals, even when he was out of power, even when he was sort-of in his wilderness phase.

He always got a good reception from the military in Pakistan. And that made an impression on him.

He was not someone who knew Indian culture or Indian society, particularly well, or Pakistani culture or Pakistani society. His meetings tended to be with government officials and there, the Indians were quite rude to him. And that, definitely, didn't help.

All of those perceptions are framed by India's tilt towards the Soviet Union during the Cold War which was something that Nixon who was fiercely anti-Communist, definitely, did not like.

You also write about the whiskey-drinking (General) Yahya Khan (Pakistan's military ruler) who Kissinger thought of him as a bit of an idiot. There seems to be a dark comedy.

Yes, but Kissinger thought a lot of people were idiots.

There is this sort-of at the level of these senior personalities, there is this dark comedy. But when you look at the outcomes, it is all terribly tragic. But Nixon has real affection for Yahya Khan.

Nixon, who is a solitary and inward kind of man, has a hard time making friends and relating to people, but he is very impressed with Yahya that Yahya seems to be this dashing, Western educated military guy with a sort of British affectation with a swagger. Nixon is very taken with him.

Throughout the year 1971, Nixon is not just saying, well, the Pakistani military are kind of bastards, but they are our bastards and we need them. And he is not just saying, they are our Cold War allies.

What Nixon is saying which is captured on the White House tapes is that Yahya is a decent man, Yahya's an honourable man.So he really has a kind of remarkable, personal loyalty to Yahya throughout the crisis.

It starts out with a higher opinion of Yahya and then actually meeting with him in July 1971 in Islamabad, Kissinger comes away from that convinced Yahya is actually a kind of an idiot and tells Nixon that a couple of times -- which Nixon particularly doesn't like.

Kindly ...

Had Nixon had a better, more favourable opinion of Indira Gandhi, would it have changed the course of things, this terrible history?

I think it would have made some difference. It is hard to tell, exactly, how much.

I think on the one hand, you have the big structural factors of the Cold War and India's pro-Soviet politics that, I think, any American President would have disliked.

Dwight Eisenhower didn't like India's pro-Soviet leanings, John F Kennedy didn't like India's pro-Soviet leanings... So, that is not unique to Nixon.

But Nixon has particularly, bad blood with (Indira) Gandhi and she with him. I mean she hates him too -- there is no question that this is mutual animosity.

So, it is very hard for them to communicate; there is not a lot of trust between these two leaders at a time when it might have been helpful.

If (Indira) Gandhi had been making appeals to Nixon and he had been willing to listen, it might have helped. But she would sometimes say things which the US government knew were outright lies.

She would say that India is not backing the Bengali guerrillas operating inside of East Pakistan, who were operating with massive secret support from the Indian government.

The US government knew that. It had a pretty good sense of the scale on which India was backing this Bengali insurgency.

So, when (Indira) Gandhi would tell the Americans, 'We have nothing to do with this,' that would have undermined her credibility, no matter who the president was.

(Indira) Gandhi would say time and time again, 'No, no, no, we're not backing the rebels. We respect Pakistan's sovereignty.'

You write that you requested Kissinger to be interviewed and he refused...

I actually requested an interview with Kissinger four times. He or his office ignored the first two (times). I never got an answer. Finally, I got an answer back from him refusing; and, then after that I sent a final appeal saying 'Are you sure here are some of the things that I am going to have to talk about in the book and I'd love to have your perspective so that I can include it in the book.'

I really do want to include the perspective of everyone who is involved in the crisis. Certainly, I would have loved to have heard from Kissinger so I could put that in the book.

Because he would not talk to me, I had to rely more on his staff. There were two officials working on South Asia; one was working on China.

I spent a lot of time talking to them to make sure that I was getting the White House perspective to include that in the book. You know, just to be fair you want to include everyone's perspective.

What kind of perspective were you looking for from Kissinger, if you had spoken to him, met him?

I wonder if he feels any sense of regret. I wonder if he still is thinking from a real political perspective. If he sees any missed opportunities to change the relationship between the United States and India when India was desperate for help with millions of refugees, as many as 10 million refugees who fled from East Pakistan into India.

I wonder if he thinks that there were any missed opportunities to try and improve the US relationship with India.

I don't think you were ever going to rip India completely away from the Soviet Union. But he could have changed the relationship, made it better. I wonder if he sees any missed opportunities there.

When you were writing the book, Nixon was gone a long time. If he were alive, would you have asked Nixon the same question you might want to ask Kissinger?

I would have asked similar questions although there are some points where Nixon and Kissinger disagreed. Nixon had more of a sentimental fondness for Yahya; Nixon had more of a racial animosity towards India.

Kissinger indulges (him) when Nixon says the Indians need a massive famine, Kissinger doesn't contradict him or say that is too much. He says they (the Indians) are such bastards.

But there is an incident in December of 1971, during the war between India and Pakistan, which results in the creation of independent Bangladesh where Kissinger has the idea that the United States will secretly ask China to mobilise troops in the Himalayas to challenge India and that will sort of pull some Indian troops away from fighting in the west and in the east with Pakistan and pull them north to take this possible risk of a Chinese intervention.

There is considerable danger attached to that because if China really did get involved in the war, then the Soviet Union would have to get involved to back up India, and then the United States would probably have to get involved to back up China.

Nixon had a good point of view -- that this is a crisis that is not likely to turn out well. Pakistan is militarily outgunned and Pakistan is going to lose the war. Let us cut our losses, let us not invest too deeply in this.

Kissinger is urging Nixon that this is a crucial moment. He says I consider this our Rhineland. So he makes a comparison to the run-up to World War II.

For Kissinger, it is a crucial moment where he also compares it to the Suez; the crucial moment where the United States needs to firmly stand up against the Soviet-backed aggression as Kissinger sees it.

But Nixon is unconvinced and he winds up saying he does not want to risk it.

It is Kissinger who keeps pushing him and finally gets Nixon to move forward in this potentially quite dangerous confrontation with the Soviet Union.

I wonder, in retrospect, if Nixon would have regretted that.

I wonder if Nixon thinks he got bad advice from Kissinger.

Kindly ...

In what way did Kissinger push Nixon into possible confrontation?

He says to Nixon that 'If we don't stand up to the Soviets here that they are going to see that we are weak and they are going to poke at us in all sorts of other places: In Indonesia, and in the Middle East.'

'If we don't show strength here in South Asia, then you should expect Soviet challenges in lots of other strategic parts of the world.'

And that is the argument that helps to convince Nixon.

Kissinger also says the Soviets will fold, the Soviets will back down every time we stand up to them.

To my surprise, I would have thought they would at least have had a discussion about what will we do if the Soviets don't back down, what if the Soviets escalate. Interestingly, they don't have that conversation.

So I think that is bad advice to the President. You always want to give the President a range of likely, possible, scenarios.

It is possible in the war of 1971, that the Soviets would have felt a considerable pressure to support India.

You also write about how Kissinger tried to take credit for the ceasefire in West Pakistan.

Yes, Kissinger come out of the war, believing that there were people in the Indian government who wanted not just victory on the eastern front, not just liberation in the independent Bangladesh, but also wanted an opportunity to prosecute a major war effort against West Pakistan.

It is not clear whether Indira Gandhi took that particularly seriously. The Indian records about the war are quite incomplete. American records are much more complete.

So we know a lot more about the American government's decision throughout this period, including on the war.

The Indian government's papers are not as nearly comprehensive as what you get on the American side except when you actually get to the war when there is very little on the archives as to what the Indian government was really thinking.

What we do know is that (Indira) Gandhi chose not wage a wider war to rip apart West Pakistan. The fighting on the western front was much more inconclusive.

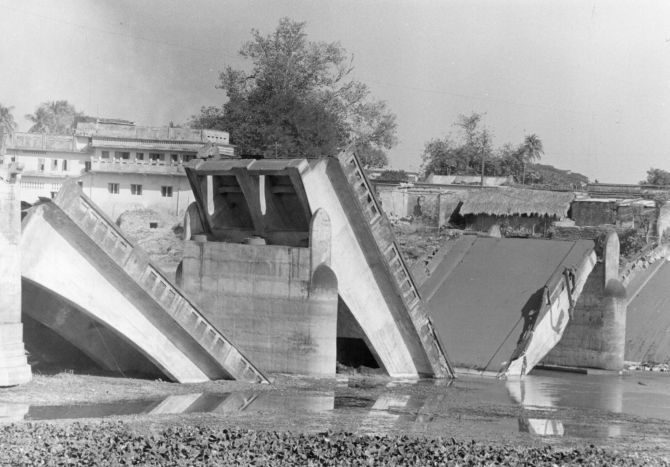

On the eastern front, the Indian forces, helped by the Bengali rebel forces, were doing very well. But on the western front, it is really brutal and bloody.

Some of the most terrible fighting of the war were those pitched tank and artillery battles on the western front.

So it is not like you see imminent, decisive, victory over West Pakistan. There is the danger that continuing the war against West Pakistan might bring China or the United States to do some sort of intervention. And you never know how well a war is going to go.

The Indian war effort had gone quite well in the east; but that is no guarantee that it is going to go well in the west.

West Pakistan is really a much, much, tougher military objective than East Pakistan was.

So, (Indira) Gandhi makes the prudent decision thinking that we did well in the east. So, let us have a ceasefire. Kissinger and Nixon think it is because of the steps that they have taken to try to threaten India, so the secret move to try and get the Chinese to move troops on the northern front.

They think it is due to the arms transfer to West Pakistan which takes place during the war even though the White House staff, the State Department staff and the Pentagon lawyers warn that this is illegal.

The famous intervention of sailing the USS Enterprise into the Bay of Bengal is something that is deeply resented in India. Nixon and Kissinger think these actions taken together saved West Pakistan.

Kissinger says, 'Congratulations Mr President, you saved West Pakistan.'

They believe what they want to believe...

If anyone saved West Pakistan, it is the Pakistani troops who fought very, very bravely against India.