This week marks the 4th anniversary of the Voyager 1 spacecraft crossing over from our solar system into interstellar space.

Prathmesh Kher/Rediff.com recalls how a planetary mission became interstellar in scope with the addition of a simple gold-plated disk.

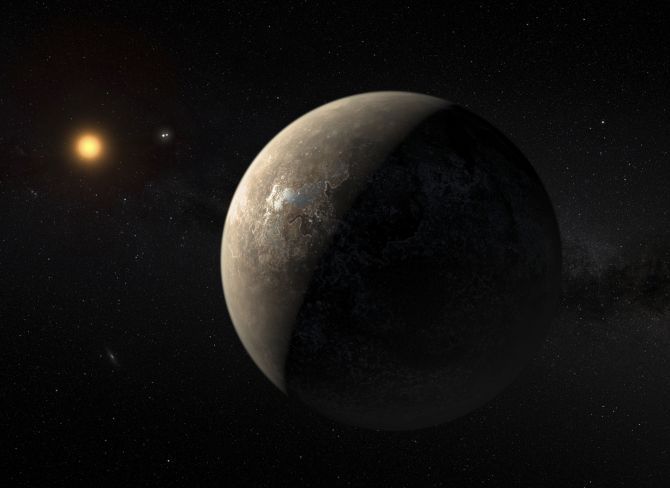

Remember the old story of Goldilocks and the three bears? Sure you do! The ‘just right’ quality of the chairs, the porridge and the beds rings true to date. Well, astronomers have found a planet near Proxima Centauri, the star nearest to the sun, which falls in the astro-biological ‘Goldilocks zone’.

A ‘Goldilocks zone’ is that ‘just right’ principle being applied to planets instead of porridge. Its more commonplace sounding variant is the ‘habitable zone’, meaning that planet is at a distance from its star that allows temperatures mild enough for liquid water (aka the stuff of life) to pool on its surface.

However, this has not been a quick find. Astronomers have been hunting intensively for planets around Proxima Centauri for more than 15 years.

Interestingly, Thursday also marked the fourth anniversary of the Voyager 1 spacecraft crossing heliopause and entering interstellar space (it only took 35 years to do so).

This makes the Voyager 1 probe the farthest manmade object from earth. That would be awesome enough but its gets even better. Before it was launched, NASA placed an ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a gold-plated phonograph record intended as a sort of time capsule.

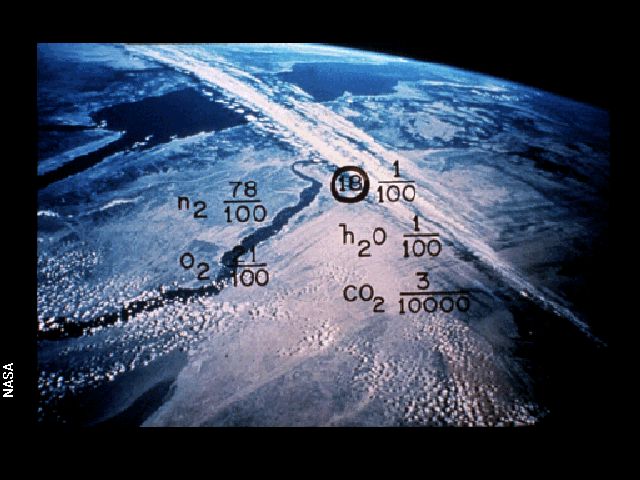

The 12-inch gold-tinted copper disk contained images and audio clips intended to reflect the diversity of life and culture on earth in case the spacecraft was ever intercepted by aliens.

The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee helmed by the imaginative Carl Sagan. The team agreed upon 115 images (external link) and a potpourri of sounds (external link), including those made by surf on the beach, a moving locomotive, an exploding volcano and animal sounds including those of birds, whales, and elephants.

This was backed up with an eclectic selection of music (including Indian singer Kesar Bai Kerkar's rendition of Jaat Kahan Ho) chosen to reflect different cultures and eras, and 55 greetings spoken (external link) by earthmen and women in different languages, including one in English by Sagan’s son Nick. Among the languages represented on the disk were India’s Hindi, Telugu, Punjabi, Gujarati, Kannada, Punjabi, Bengali, Marathi, Urdu and Odiya.

At the time Carl Sagan had noted: "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet."

The disk also includes a cosmic map, imprinted on its skin, which would allow any extra-terrestrial species to find their way back to Earth. The pulsar map, as it is called, shows the location of our solar system with respect to 14 pulsars, a neutron star that emits regular pulses (hence pulsar) of polarised radiation, whose precise periods are given.

While all this might seem like navel-gazing (or star-gazing, to use a more appropriate term), it is in fact not. Looking at the night sky happens to be our most ancient ritual.

Humanity is naturally wedded to the stars. It is in our nature. Whether it is Aboriginal rock art to Van Gogh’s The Starry Night to the more recent Star Wars craze, people love to look up at the night sky. Children, long before they are told to look down while walking, are fascinated by the high above.

Perhaps the future of Proxima b might also include a disk.

Carl Sagan once said: "If we receive a message, it can’t be from anybody less capable than we, because anybody less capable can’t communicate at all.”

Well, here’s hoping that someone out there sees us just as we saw Proxima b.