Gajendra Chauhan is just one the many troubles that ail the national film institute. But all may not be lost yet, Ranjita Ganesan.

Little over a month ago, students of the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune were forced to do a frantic Google search for "Gajendra Chauhan".

The man, known for playing King Yudhishthir on the late-1980s Doordarshan show Mahabharat, had been named the new chairman of the institute.

Until several media reports and former FTIIians confirmed it, the news had seemed like a joke.

To most FTIIians, Chauhan who played small parts in movies and TV and used that fame to campaign for the Bharatiya Janata Party during elections, seems largely irrelevant in a world of high art and cinema.

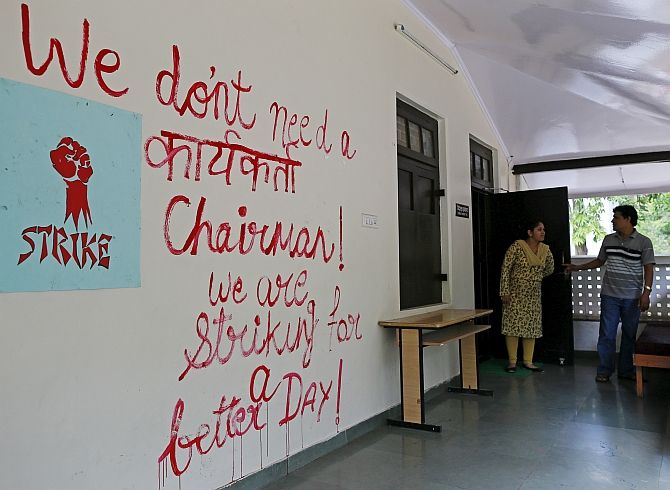

Dubbing him a "puppet" and his appointment "brazenly political", the student body decided to protest with a strike.

When the government announced last year that the famed institute would be accorded "institute of national importance" status, there was hope for more autonomy as well as upgrade of the academic and physical infrastructure, says Swapnil Ninawe, a student of direction.

There was even talk of giving it "centre of national excellence" honour, which would boost its scope and independence.

For the moment, the institute feels misunderstood.

Under the Union information & broadcasting ministry, it is being treated more like a media unit than an educational institution, Ninawe says.

There have been chairmen with political affiliations before but they were appointed in good faith, observes sound recording student Surya Samaddar, offering the example of actor Vinod Khanna of BJP.

"But promoting someone with such weak credentials suggests the work we do as film makers is only secondary to political servitude."

Besides Chauhan, students believe some other appointments are also aimed at "saffronising" the institute.

Ajayan Adat, who studies sound recording, was among four students allegedly roughed up by activists of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad two years ago for screening Anand Patwardhan's documentary Jai Bhim Comrade at the neighbouring National Film Archive of India.

Narendra Pathak, the Maharashtra president of ABVP, is now a part of the FTII governing council.

"How can we feel safe?" asks Adat.

Also part of the council now are Anagha Ghaisas, member of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and Rohan Solapurkar, an actor who was reportedly in contention for a BJP ticket in the last state assembly elections.

The campus brims with discussions on the likes of Andrei Tarkovsky and Ritwik Ghatak. Quotes by Satyajit Ray and Albert Camus adorn the walls.

By his own admission, new chairman Chauhan is unacquainted with international cinema.

The meetings of an FTII delegation with I&B officials and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley did not bear fruit as the core issue of removal of new members was ignored, say students.

Instead, they were assured that existing administrative challenges would be addressed.

Some in BJP argue that while he is not an art-world heavyweight, Chauhan should be given a chance because he could prove an able administrator.

"The students were granted an all-pervading wish list. But (they) continue to adopt a 'my way or the highway' approach," I&B sources say.

The deadlock continues.

In a limbo

It is the morning of day 34 of the strike.

A general body meeting had kept most students awake late into the previous night, and only a handful of them have stirred and made their way to the protest's headquarters, a marquee next to the legendary "wisdom tree" whose sweeping green foliage is believed to have brought calm and clarity to generations of FTIIians.

Campus dogs are resting on mattresses here, while students create posters and graffiti art on themes of freedom and rebellion.

Academic activities have not entirely halted. They take place informally outside.

A day earlier, students had screened Fandry and held interactions with its director, Nagraj Manjule.

On the day of our visit, they plan to have a reading of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot and then screen some diploma films of ex-FTIIians.

Also, at the hostel and in the canteen, a few appear to be working on or discussing projects.

But over a month into the protest, the ardent marching and sloganeering have subsided.

The institute wears a disturbed yet weary look that signals both unfulfilled pleas and slowdown.

Many of the students are from batches starting in 2008 and 2009, but have still not graduated.

The three-year courses take at least over four years, and sometimes more to finish.

The lag is mainly because of the shift from analog to digital technologies that came around 2009-10.

Most equipment has been upgraded now. But the change in processes and the simultaneous rise in the intake of students owing to reservations have strained resources.

Most work related to sound production requires students to travel to studios in Mumbai, where they have to wait for their turn until work on commercial Bollywood films ends. One large film studio and another smaller one are being shared by students on the Pune campus.

D J Narain, outgoing director of the institute, looks an anxious man two days before the end of his four-year tenure.

Students, who share a good rapport with Narain, had requested that the government extend his term but it later named Prashant Pathrabe in his place.

The strike has caused disruption and turned the spotlight on age-old organisational challenges, says Narain, undermining the good work happening at the institute.

During his term, the syllabus has been revamped with the help of professors and students, he says.

After the move to digital, the faculty is trying to bring discipline in some areas like limiting the amount of footage shot, says Bharat Murthy who has been teaching direction on contractual basis since 2012.

The government also raised questions on the output at FTII not being commensurate with investments.

It said it spends Rs 13 lakh on each student and Rs 40 crore on the institute annually. However, students disregard the claim.

They say the figure is skewed because it simply divides total expenses by the total number of students without taking into account spending on immovable assets, faculty and other employees.

As for the complaint about the quality of output (Chauhan and some BJP members stated there had been no major FTII success story since director Rajkumar Hirani), most film practitioners and the outgoing FTII director disagree.

Narain says the students have consistently won a high number of National Awards.

Other than Hirani who has had commercial success, film makers like Amit Dutta and Umesh Kulkarni have contributed to more experimental styles, winning praise at international film festivals, he adds.

Film maker Sudhir Mishra points out that most successful technicians in cinematography and sound come from the institute.

Avinash Arun, an FTII graduate in cinematography, recently made his directorial debut with the National Award-winning Marathi film Killa.

Arun, who is from Solapur, says his family had no connections with the film industry but the institute became a "second mother" to him.

"The freedom and world view that place gives is amazing," he observes. "In art and cinema, two plus two is not equal to four. They need a sensitive person on the chair of such a sensitive institute."

Room for improvement

However, FTII has room for improvement.

The faculty is woefully underpaid, notes screenwriter Anjum Rajabali, who is honorary head of the screenplay writing department since 2004.

"Too many of them are on contract, making them vulnerable and insecure. There are no programmes to upgrade their own learning and knowledge, no incentives for self-development."

The composition of students is also changing, says Professor Murthy.

Despite reservations, a majority of the students are fairly well-off, bringing their own equipment and having previous work experience.

"FTII will need to consciously reach out to the economically disadvantaged sections. That is the only way a government institution can stay relevant."

In moves purportedly to raise pressure on the agitators, a rustication warning was issued to students and no renewal orders were given to contractual faculty whose terms ended recently.

While the students' position is justified, the government appears to have made it a prestige issue, says Rajabali.

"The only way perhaps to resolve this, without either compromising on their respective stands, is to speed up the process of turning FTII into a Centre of National Excellence with immediate concrete steps. It's high time, anyway," he adds.

"It will also accord FTII greater actual autonomy and reduce the possibility of political interference."

Will the BJP-led government, which has shown no sign of backing off on the Gajendra Chauhan affair, agree?