I K Gujral's place in Indian history may not run into several pages. But he will always be remembered as a decent gentleman, generous and kind to a fault, who nursed a dream for a peaceful, prosperous India, in harmony with the world.

I K Gujral's place in Indian history may not run into several pages. But he will always be remembered as a decent gentleman, generous and kind to a fault, who nursed a dream for a peaceful, prosperous India, in harmony with the world.

T P Sreenivasan pays tribute to his mentor.

Inder Kumar Gujral (IKG) was every inch a gentleman and an aristocrat in lifestyle, demeanour, clothes, food and personal relationships. But he was also a Socialist in thoughts and goals and a patriotic Indian.

Through the twists and turns of his political life, which brought him to the helm of affairs in India for less than a year, he never changed in those fundamental traits, even if he changed loyalties and embraced unusual coalitions.

IKG may have left a mixed political legacy, but no one who has worked with him will ever forget his affection, loyalty and easy informality. Ever since I worked with him in our embassy in Moscow in the mid-1970s, he was my mentor.

Whether he was my ambassador, a politician in the wilderness, the minister of external affairs or the prime minister, he had time for an affectionate hug, a kind word and a generous deed.

I felt comfortable in discussing political, diplomatic and personal issues and he was always warm and sympathetic in responses. As external affairs minister and prime minister, he shaped the latter part of my diplomatic career without my asking for any favour.

IKG is often referred to as an 'accidental' prime minister. But his resume fits a prime minister any day. Both he and his father were in British prisons as freedom fighters. He worked his way up to Parliament in the Congress party and attracted the attention of Indira Gandhi, who inducted him into the Cabinet.

He was a highly successful minister, who found his way into Indira Gandhi's 'Kitchen Cabinet' and fell out of favour only because of Sanjay Gandhi. He had a successful innings as ambassador to the Soviet Union under two regimes in India and rose to become the external affairs minister twice.

At the end of such a career, there was nothing 'accidental' about his being prime minister except that it was the turbulence of coalition politics that brought him to the top. He was a suave and conciliatory leader, but capable of courageous decisions, some of which led to the resignation of his government.

I recall vividly the arrival of IKG and Sheila Gujral at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport one cold morning amidst speculation that his was a punishment posting. We expected him to sulk and struggle to get back, rather than get to work in right earnest.

But he astonished us with his zest, agility and messianic zeal to strengthen Indo-Soviet relations. No other ambassador since the legendary KPS Menon (Sr) was as committed to Indo-Soviet relations as IKG was.

He was aghast by the state of the embassy and the ambassador's own chamber, which was shifted to the basement by one of his predecessors and began to make changes to suit his aristocratic temperament.

As the head of chancery, the brunt of the renovation work fell on my shoulders. He was often impatient with the progress of work, but reminded me of the remaining work again and again as though he was saying it to me for the first time.

The ministry of external affairs questioned some of his decisions, but he went on regardless in a manner only a seasoned administrator could do. Within a year, the embassy and chancery had a new look, not ostentatious, but elegant, we had a fleet of new cars and a lovely garden. The ramshackle 'Napoleonic Dacha' and the squash court in the compound came back to life.

His diplomacy was fairly transparent as Soviet policy towards India was steady and the multifarious activities of cooperation we had did not require any cloak and dagger operations. There were no major issues to resolve or equations to establish.

He handled the Soviet bewilderment of Indira Gandhi's defeat, the advent of Morarji Desai and the return of Indira Gandhi with equanimity and explained the will of the people and the mysteries of Indian democracy to the Soviet leadership.

The continuity he provided was a blessing to both India and the Soviet Union. He was as enthusiastic in interpreting Soviet policy to India as he was in selling Indian policies to the Soviet Union. He was instrumental in removing some of the prejudices in Morarji's mind about the Soviet Union.

He travelled extensively in the Soviet Union, even to Siberia, and was greatly impressed by the country's potential. He was convinced that the 21st century belonged to the USSR and said so in a cable to the prime minister.

Since it was classified as most urgent, External Affairs Minister Yashwantrao Chavan was woken up from sleep to read it. An irritated Chavan is supposed to have exclaimed: 'Isn't there a little time before the 21st century dawns on us?'

It was after a visit to Sochi that IKG returned with a beard that stayed with him for the rest of his life. I asked him about it at the airport. (Other colleagues kept a discreet silence.) He replied that a female barber in Sochi discovered how much like Lenin he would look if only he had a beard. He accepted her suggestion that it would be great for an ambassador in Moscow to look like Lenin.

He was in political wilderness for a time after his return to Delhi, but he had enormous influence in the city and he helped me to get school admissions, accommodation, gas connection etc like a local guardian would do.

But suddenly when he became the external affairs minister, I felt that I suddenly lost a great contact in the big city. But having him as my own minister was a great asset, even though I did not need to go to him for anything.

After my wife and I became victims of a vicious attack, IKG insisted that I should move out of Nairobi, though I was inclined to stay on. As prime minister, he seized the first opportunity to post me to Washington, an offer I could hardly resist.

As prime minister, he was as enthusiastic about the US as he was about the USSR during his days in Moscow. I had looked after him on a visit to New York as a delegate to the UN, and introduced him to a number of people there. His friends in New York became our friends too.

I met him in Delhi when he had just come back after his first meeting with President Bill Clinton. He told me with boyish enthusiasm how well that meeting went and how constructive Clinton was about India-Pakistan rapproachment. He said he was sending me to Washington to prepare for Clinton's visit to India. One of his great disappointments was that his government fell before Clinton could come to India.

He had made friends with India's point man in Washington, Rick Inderfurth and their mutual admiration led to a cartoon in which a boy was asking his father whether Inder Gujral and Inderfurth were brothers.

When IGK came on a private visit to the US much later, Inderfurth gave him that cartoon for his autograph. 'You never know,' IGK wrote on the cartoon before signing it.

Though IGK was a protege of Indira Gandhi, he saw himself in the mould of Pandit Nehru, the great peacemaker. Like Nehru, he had no ill will or malice to anyone.

His Gujral Doctrine was a reflection of this mentality. When he visited the UN as an MP, he used to challenge some of the assumptions of our policy towards our neighbours, particularly Pakistan.

He was pained at some of the exchanges we had with Pakistan and he never participated in them. His conversations with Nawaz Sharif were in Urdu. He told me once that they had agreed that India would never be able to give Kashmir to Pakistan, nor Pakistan would be able to take it. That, he thought, was a good beginning to start a dialogue

He had no hesitation to withdraw the IPKF from Sri Lanka. He was perhaps disappointed that the doctrine did not go very far, but he persisted as long as he was in power. It was only his anxiety to save the Indians in Kuwait that he embraced Saddam Hussein in Baghdad, which was misunderstood around the globe.

I never missed an opportunity to call on the Gujrals whenever I was in Delhi and I saw the deterioration of their health each time I saw them. But the conversations were all about Moscow and common friends and in a cheerful and jovial mood. Both of them discussed their book projects with me and sent me copies as soon as they came out.

IKG did not forget to send a copy of his book even to my son in New York, whom he knew as a little boy. His office had a hard time finding out his official name, as IKG knew him only by his pet name.

The last time I met him a year ago he marveled that the little boy had grown to become a professor at Columbia and even had twin children. "Give them and Lekha my love," were the last words he spoke to me.

IKG's place in Indian history will not run into several pages. But he will always be remembered as a decent gentleman, generous and kind to a fault, who nursed a dream for a peaceful, prosperous India, in harmony with the world.

T P Sreenivasan is a former Ambassador of India and Governor for India of the IAEA, Executive Vice-Chairman, Kerala State Higher Education Council, Thiruvananthapuram, and Member, National Security Advisory Board, Member, India-UK Roundtable, and Director General, Kerala International Centre, Thiruvananthapuram.

For more columns by T P Sreenivasan, please click here.

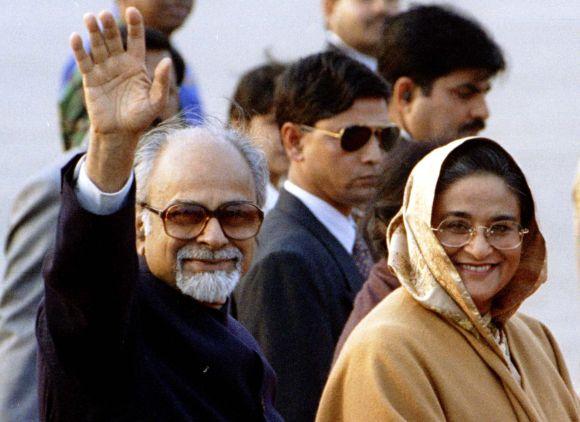

Photograph: I K Gujral with Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina at Dhaka airport in January 1998. Photograph: Rafiquar Rehman/Reuters