'Just how strong were the ties between the world's largest and oldest democracies that an incident involving a diplomat and a maid led to anger threatening the relationship itself? Or had the relationship been weakening in the past few years, masked by the empty symbolism of State dinners, asks Devesh Kapur.

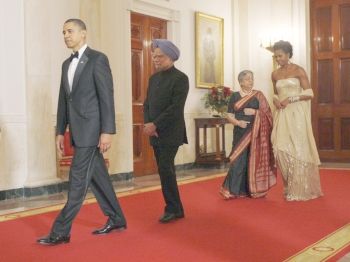

The sharp deterioration in India-US relations stemming from Devyani Khobragade's arrest raises a question: Just how strong were the ties between the world's largest and oldest democracies -- whose common value systems supposedly make them 'natural allies' -- that an incident involving a diplomat and a maid led to angst and anger threatening the relationship itself? Or had the relationship been weakening in the past few years, masked by the empty symbolism of State dinners?

The sharp deterioration in India-US relations stemming from Devyani Khobragade's arrest raises a question: Just how strong were the ties between the world's largest and oldest democracies -- whose common value systems supposedly make them 'natural allies' -- that an incident involving a diplomat and a maid led to angst and anger threatening the relationship itself? Or had the relationship been weakening in the past few years, masked by the empty symbolism of State dinners?

A strong bilateral relationship is like a healthy garden -- you need to ensure the soil is fertile, plant the right seeds, nurture it, and weed it. Gardens reflect the care of their gardeners. As Rudyard Kipling said, 'Gardens are not made by singing, "Oh, how beautiful" and sitting in the shade.'

The underlying basis of the transformation of the India-US relationship was India's rapid economic growth -- the best foreign policy today. Both countries lost the economic plot after 2008. India's self-inflicted economic wounds are unlikely to heal soon. So, key supporters with an economic stake in India -- American business and non-resident Indians, NRIs, who heavily lobbied for India in the last decade -- have little reason to do so now.

They have actually become vociferous critics in some cases -- hardly surprising, given how fed up Indian business is of its government. This criticism has been myopic, exemplified by their staunch opposition to India's stance on intellectual property rights of medicines and the solar panel dispute in which the US has dragged India to the World Trade Organisation, WTO.

There are reasons to believe that the new Indian patent law may run afoul of the WTO, but US criticism of the Indian Supreme Court's ruling on repetitive patents seemed to emphasise 'my rule of law' rather than upholding the broader principle of 'rule of law.' And dragging India to the WTO on solar panel subsidies was strange, given that the primary beneficiaries would be Chinese, not American, companies.

But these lobbies also have good reasons to be unhappy. The root of the current crisis is the unravelling of the India-US nuclear deal, once hailed as transformative and now the poster child of aborted hopes and bitter recriminations.

US business lobbies, NRIs and the Indian government worked with the US government and lobbied extremely hard for an agreement against the teeth of opposition from the non-proliferation lobby and patronising liberals far more comfortable with a nuclear China than India.

But instead of running with an amazing breakthrough, a weak Indian government fumbled, passing a nuclear liability law that no other country had and no international supplier could ever agree to.

Indeed, to ensure the US's support to obtain the waivers from the Nuclear Suppliers Group, India voted against an important partner, Iran, in the United Nations. Five years later, no nuclear plants have come up in India. Instead, they have come up in Pakistan since China used the deal to further its agenda in that country.

Meanwhile, India's relations with Iran deteriorated and US business, which saw as its reward only headaches and few opportunities in India, has become embittered.

Nor has security cooperation gathered as much steam as expected. India has abysmally mismanaged its defence procurement, putting its security at risk and also weakening a key pillar of the India-US relationship.

The failure stems in part from India's 'We-know-best' foreign policy establishment.

Take the massive contract for the medium multi-role combat aircraft for the Indian Air Force. India was trading the best technical choice and costs with the strategic implications of picking a specific aircraft. But India did not link its discussions with the US on this issue (which was important to the US) with another issue important to India, namely the US failure to agree to a totalisation agreement with India. The latter would ensure that Indian nationals working in the US would not pay social security taxes if they returned to India within an agreed time frame.

The US has signed such agreements with 24 countries and India with 18, and some of these are common to both. The US has found reasons not to since it is effectively expropriating half to one billion dollars annually.

India could have insisted that it was prepared to award the fighter aircraft contract to the US if the latter agreed to a totalisation agreement. Neither happened -- no deals, simply more disagreements.

By failing to deliver on its commitments, India undercut its position when it did have an iron-tight case such as the shameful handling of David Headley by the US. If an Indian national had been involved in the murder of scores of Americans, the US would have been outraged if he was not handed over. But why should Americans care more than Indians themselves seem to bother about the Mumbai attacks if the apathy five years after that horrific event is any indication?

The reality is that a government that has frittered away respect within cannot command it outside. Over the past couple of years, the locus of Indian foreign policy has moved from the ministry of external affairs to the Prime Minister's Office and internal bureaucratic games -- from selection of foreign secretaries to ambassadors to the US -- often take more energy than actual policy formulation.

India's embassy in Washington was aware of the charges against Ms Khobragade in summer 2013. It could have taken the pre-emptive action of posting her outside the US, but failed to act swiftly. It could have -- and indeed the Indian government should have -- been aware that the US, especially the New York region, has been granting asylum status to increasing numbers of Indians.

According to a recent report, there was 'a sharp increase in the number of refugees/asylees, from 300 in the 1990s (and barely 19 in the 1980s) to 3,100 in the 2000s (asylees accounted for virtually the entire flow of this group),' accounting for 11 per cent of new Indian legal permanent residents in New York.

Outrage is a poor substitute for hard work.

Many of India's weaknesses are mirrored in the US. The quality of the State Department and the National Security Council personnel on the India desk reflects Washington's priorities. Hence, its unpreparedness for India's reaction was unsurprising. American elites -- like their Indian counterparts -- are only too eager to win tactical battles, while losing sight of broader strategic goals.

The US's refusal to grant Narendra Modi a visa -- the result of an exquisite cohabitation of far-Right evangelicals and the Left -- has meant that a prospective prime minister of India will have had far greater contact with China, the country that poses the single biggest challenge to the US in this century.

Senior US officials actually believe that if Mr Modi comes to power, they will give him a visa and he will move on -- demonstrating that self-delusion is a necessary precursor of decline.

With the most recent saga, the US has achieved a near-miracle -- uniting all Indian political parties, for once, against it. It has performed a similar miracle in neighbouring Pakistan -- the US has made itself even less popular than India after having given that country tens of billions of dollars in aid.

Both countries have joined to weaken the economic, security, political and bureaucratic stabilisers of their relationship, which means that the only miracle unlikely to transpire soon is a robust India-US relationship.

Dr Devesh Kapur is Director, Centre for the Advanced Study of India at the University of Pennsylvania.

Image: President Barack Obama, Dr Manmohan Singh, Michelle Obama and Gursharan Kaur at the State dinner the American president hosted for the Indian prime minister in November 2009. Photograph: Jason Reed/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025