'When the virus, in a way, tires itself out, because it is not finding any more people to attack or keep itself viable, that is when the peak actually has been reached and you are on the downward limb (of the curve).'

There is just one burning question we all have.

When will COVID-19 leave?

When will this wretched, uninvited virus start exiting our lives?

The next question that reasonably follows: When will India's cases of COVID-19 peak?

Dr Gudlavalleti Venkata Satyanarayana Murthy has the most unusual answer to this question.

He doesn't think there is any one date or period when COVID-19 will peak in India.

That is simply not possible.

Read on, for his logical explanation.

Dr Murthy, who is Hyderabad based, is the director, public health at the Public Health Foundation of India, a non-profit working for a 'healthier India'.

He is also a professor in public health disability with the International Centre for Eye Health at the London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London.

A public health physician by discipline, who did his qualifications in Guntur, Delhi and London, Dr Murthy has a special interest in bettering community health and has been/is the principal investigator for multiple projects in India, Nigeria, Bhutan, Nepal Bangladesh and Pakistan.

While working at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, he started India's first department for community ophthalmic medicine.

The public health expert gives Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com the real lowdown on peaking and more.

In a recent interview you said India should not be seen as one entity in the battle against COVID-19.

It needs to be looked at on a state-to-state basis.

And that certain states are already peaking and some are near peaking.

What was your reasoning?

When do you foresee that the states that are near peaking, will peak?

There are a number of things to consider when you look at peaking.

It is not just something like the monsoon hitting the Kerala coast on the first of June.

It's not as straightforward as that.

What generally happens is: You (a state/area) peak when you start coming down in terms of the number of people who can be susceptible, or who can catch the infection.

That is the time when that number starts decreasing -- what one calls R0 (basic reproductive rate which decides how infectious each virus is going to be and during the disease period how many other people a patient will infect).

Peaking depends on a number of factors; the most important being what proportion of the population has been exposed to the infection.

When the virus, in a way, tires itself out, because it is not finding any more people to attack or keep itself viable, that is when the peak actually has been reached and you are on the downward limb (of the curve).

We look at peaking in terms of what is the Ro in terms of the current time. You call that Rt (virus's actual transmission rate at a certain period) which actually is the R0 at a particular point in time.

States where the replication rate is coming down below zero, or to 1, or below 1, (indicates that the situation) is already at the plateauing stage and on the descending limb,

States, where R is between 1 to 1.2 and 1.25, are nearly there, so, in a way, the virus's replicability pattern has been exhausted to a great extent.

That is how we comment on when COVID-19 would peak.

In dealing with a country with so much of diversity, you can't talk about one peak for the entire country, till all the states have achieved it.

That is why there is going to be a need to look at a state's specifics and states like UP differently, and even districts first.

Even in Maharashtra, district specific peaking has to be looked at.

So, if you look at Maharashtra, as a whole, it may take another 10 days, 12 days for the state to peak.

But it could be that when you look at a district like Gadchiroli, or some of the districts which are closer to the Chhattisgarh border, at the district level, the peak might already have been passed, though the state as such has not peaked. Some districts within the state could have already done that.

We should never look (create a picture) with one brush stroke, right across, when we look at a country like India.

When we look at some of the states like Bihar, where it is the migrants who actually started bringing in the virus into the state, they may be far away from the peak. Not just in terms of even thinking of the peak, but even the rise may occur only towards mid-July.

So, there can't be one peak.

But states, where already there has been a large amount of exposure, they would peak earlier than those states, where there has been slow exposure, like in Bihar.

You can expect that by middle of July, maximum, states, like Maharashtra, Delhi, Tamil Nadu, they should all be past the peak. Whereas for states like Bihar, it can take much longer.

May I understand this a little bit better.

From what you just explained, peaking sort of involves the arrival of a little bit of herd immunity in an area.

And it's not only about lack of exposure.

Those of us, who have been home, locked down in our flats, are not exposed to herd immunity.

So, it's a mixture of both lack of exposure as well as a little bit of immunity?

Yes, it's a mixture of both -- plus the fact that the virus has a viable period during which it can survive.

The virus can't survive, you know infinitely.

If it does not get people whom it can infect, then the virus naturally dies down.

Any organism, whether it is a cholera bacterium or whether it is the virus for a common cold/flu, if it does not get a chance to infect somebody else, it dies.

Viruses do not naturally exist in the air (indefinitely), like the stars or the moon.

They have to have a host.

If they don't get a host, they die out naturally.

That is what the lockdown is doing -- keeping people away from the virus.

It is not building herd immunity, but it is keeping people away from the virus, so that the virus, in a period of two to three weeks, when it does not get an opportunity to infect others, could slowly start dying down or lose its potency to replicate inside another human being.

If the virus is exposed to sunlight for a long period, then even if it infects a person it will not be in a position to replicate or reproduce in the new host.

Any disease needs a host -- without the host it cannot survive. It's a parasite. It needs a host.

So, whether it is through herd immunity, where there are no more people whom it can infect, or through lockdown, where you are keeping people away, like you just mentioned, from the virus -- both ways ultimately the virus has to die down.

The lockdown is lifting or has already lifted in parts of India.

It has partially lifted, in bits and pieces, in some places where the peak has not been reached.

Does that mean that the peak for those places will then move ahead?

Or will alter?

Well, obviously the peak has not moved ahead in a state like say Bihar or Assam. Or even the north east.

Last month the north east had nothing (no cases). Today, you find, after people have come back from other parts of the country, or the world, cases now have been reported in Mizoram, in Assam, in Meghalaya. Cases which were not there before. Just three weeks ago there were no cases.

Now there, peaking will take much more time.

But you cannot have something like a perennial lockdown, where everything stops.

Life has to go on. You just cannot expect that people would continue to be compliant.

I'll give an example of what is happening, in terms of hospital care: In the UK, this week, we had data released. There were nearly 45,000 excess deaths, which occurred in the UK during the lockdown -- of which 30,000 were attributable to COVID-19.

But another 15,000 were deaths from causes like diabetes, dementia, and other respiratory problems, where people were scared to come to hospitals and were dying at home.

If you have lockdown, there is going to be a cost both in terms of mortality -- not talking about unemployment -- in terms of mortality and access to healthcare.

A child, for instance, who has cerebral palsy and needs physiotherapy, they are not getting it.

The impact this sort of a lockdown has is on the other consequences of health, which can be even more catastrophic.

You have to look at a middle path affair.

Even if there is a sort of relaxation of a lockdown in different states in different ways, shouldn't there still be a few important measures in place?

There would be certain things that are critical.

The most important is personal protection, which includes: Using your mask, having your etiquette for when you are coughing or sneezing, so that it doesn't infect others around you, sanitising, hand washing repeatedly, and keeping your distancing of at least one metre, if not two metres.

These are things that have to be enforced with or without a lockdown.

Now when you have a situation where physical distancing within the household is difficult, because of say a slum-like condition, in a place like Dharavi (north central Mumbai), or any other migrant labour camps, when you have that sort of situation, then the only alternative is that people continue to use face protection and wash their hands frequently when they're at home.

None of these are a 100 per cent guarantee against infection.

A lockdown is not a 100 per cent guarantee against infection either.

Most infections occur within a household. The household contacts, especially the spouses have a 35 per cent risk of getting infected.

Casual contacts outside, who just bump into you, the risk is as low as 0.35 per cent.

So, that's a huge differential.

The disease happens in clusters; it happens in households. A lockdown will not prevent what is happening in a household.

Lockdown is protecting what is happening in the community outside. But the risk there is only 0.35 to 0.45 per cent.

The major risk is within the household.

So even if you have a lockdown, you need these (personal protection) measures.

If you don't have a lockdown, then you need more emphasis on these measures, specifically physical distancing and use of mask, so you do not communicate the infection to somebody else in the community.

A recent article on Bihar stated that since the lockdown had lifted there was no longer any way to track new arrivals.

In spite of a degree of relaxation of the lockdown, in different states, shouldn't there still be tracking a movement at least?

If people are taking trains to go home, then they are sitting on a train for 30 hours. -- that is similar to the situation you are referring to ie of closeness in a home or household.

Shouldn't the tracking of movement of people from district to district or state to state be important?

Yes, I think that is, of course, very important.

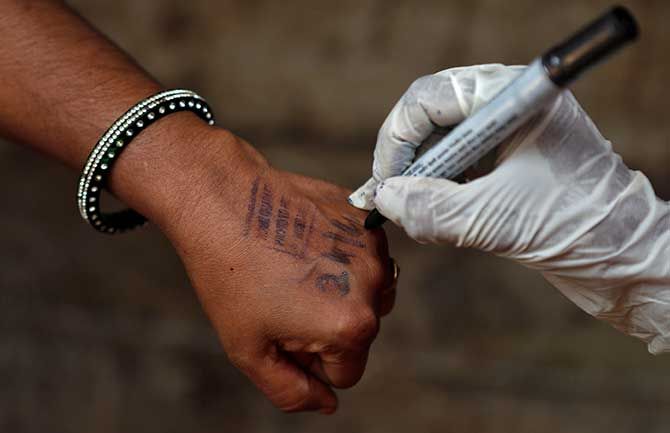

The government has spoken so much about its Aarogya Setu app.

It is easy to have everybody use an app like that, where you can track the geolocation, wherever they move, with a mobile phone. Then you are able to track their movements.

Definitely there has to be a tracking mechanism. Contact tracing is all about effective tracking. No doubts about that. That is important.

But what about quarantining people, when they reach the end of their journey, wherever they're travelling or that's not necessary if you have the app?

The problem is you have an incubation period, which can be two to 10 days.

If you quarantine people for 10 days, there is a cost to it.

Some people can show the infection on the 15th day, and they would have gone away from the quarantine, and therefore, those cases are going to be missed.

Quarantining at home, rather than an institutional quarantine, is very important.

If you have people travelling by air, then they, I presume, are people who are more aware of the things around them and therefore would not take a tablet of paracetamol to show that they are fit.

But these are the things which people are doing, right?

If people are honest enough, and you have a tracking app, which has the geolocation, where you can track them, and somebody rings them up regularly, then during the two weeks, that they are in home quarantine, somebody can connect with them to find out how they are (and prevent further spread).

If you don't do that, then there is no tracking. Having an app, where there is no tracking, is an absolute waste of resources.

Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com