Historian Stanley Wolpert, author of several books on India, passed into the ages recently.

We remember Professor Wolpert with Rajeev Srinivasan's March 1997 interview published on the occasion of his controversial book on Jawaharlal Nehru.

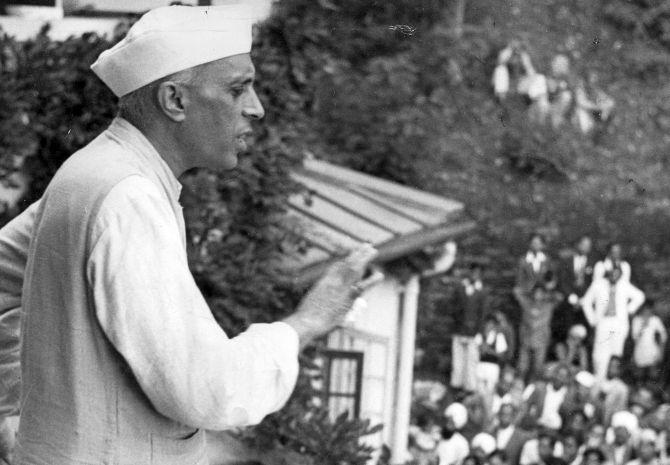

UCLA Professor Stanley Wolpert's biography of Jawaharlal Nehru ruffled a few feathers in India, drawing criticism about a less-than-totally-reverential portrait of the man considered India's 'matinee-idol' statesman.

Professor Wolpert is an expert on South Asia, and his A New History of India is a comprehensive study of Indian History.

His PhD dissertation was published as Tilak and Gokhale, a comparative biography.

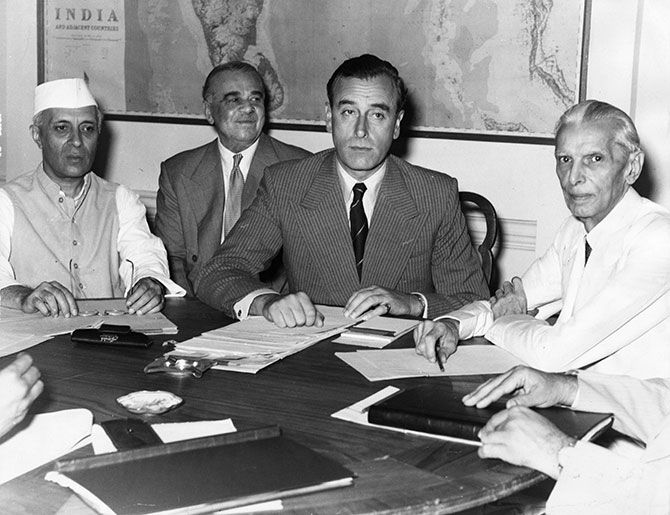

He is also no stranger to controversy: His fictionalised biography of Mahatma Gandhi, Nine Hours to Rama, was banned in India; his Jinnah of Pakistan was banned in Pakistan.

Rajeev Srinivasan spoke with Professor Wolpert by phone in Los Angeles.

You were trained as an engineer, yet on a trip to India you decided to become a historian. Why?

I first arrived in India a few days after Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated.

I saw his ashes being immersed in Bombay's Backbay.

Hundreds of people swam after that beautiful white boat, hoping to touch one of his ashes.

There was a multitude of grieving mourners, and people told me the saintly father of the nation had died.

I was twenty at the time, and was very affected by that incident, fifty years ago.

It changed my life, and I decided to learn as much as I could about that man and about his country.

You must have been very disappointed about the books being banned. What do you attribute it to?

I have never been given any reasons for the ban on Nine Hours to Rama.

I might have come uncomfortably close to the truth when I talked about the criminal neglect of the Mahatma's security.

A number of groups opposed him, some even called him Mohammed Gandhi because his prayer meetings included the Quran.

A bomb exploded in Birla House grounds behind where he was staying some two weeks before the assassination.

The police did interrogate a number of goondas, but did nothing to prevent further incidents.

I think I came close to the truth.

The head of the CID in Bombay, I had dinner in London with him years later he said, "If I hadn't sealed the documents myself, not to be opened in 50 years, I could have sworn you had read them."

As for Jinnah, Zia-ul Haq's advisor on Islamic affairs said the book could not be released in Pakistan, as I talked about how Jinnah enjoyed alcohol and pork.

A number of people asked me to delete those references so that the book could be published in Pakistan, but I didn't.

The ban was lifted in Benazir Bhutto's first term, and the book is now in print in Pakistan (and in India).

I think the truth about great men needs to be known and discussed.

I don't see anything wrong with their having failings.

Makes them more human, and maybe it will make us common folk more tolerant of each others's faults.

The biggest concern in India about Nehru seemed to revolve around suggestions of possible early homosexual experiences at Harrow.

I have only striven to present as complete and true picture of Nehru as possible.

I believe he has not really been viewed as a human being, but more as some historic icon or quasi-divinity.

I used a lot of references, including his own writings, and he certainly was human, not some god-like person.

I have tried to tell the story as honestly as possible, not like a hagiographer.

Most magnificent leaders of the world have withstood the scrutiny of historians and Nehru, such a central figure in Indian history, surely can too.

You seem to believe that if in 1922, Mahatma Gandhi had not called off the Satyagraha movement over the massacre at Chauri Chaura, things might have worked out differently.

You imply that had the 'moderates' such as Motilal Nehru and C R Das been able to work out a deal with the British, Dominion status would have been achieved peaceably by 1924.

Is this credible?

History is so full of ifs and buts and there are so many variables, it is impossible to say with certainty.

But Britain had a predisposition to grant Dominion status at that time.

The Swarajists were the most logical partners in bringing this to fruition.

If Motilal Nehru and Das had not both died early deaths they might have brought the Dominion into the Commonwealth as a united nation and that is very key.

The Muslims might have remained in the Indian Union -- they had not reached any point of no return at that time.

Is it true that the British deliberately provoked Hindu-Muslim animosity?

Was this a way of justifying to themselves the need for them to stay on in India?

I don't think there was any such grand conspiracy.

There were Englishmen, it is true, who were pro-Muslim; but then some were pro-Hindu, too.

By and large, the British wanted an environment of law and order.

If there were internecine conflict they feared they might be destroyed by a Dunkirk-like rear-guard action.

It is a misreading of a complicated subject to allege British bad faith, despite the fact that there were people like Dyer and O'Dwyer who provoked violence and who were very racist and anti-Indian.

Nobody can condone the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre, or people being forced to crawl on the streets of Lahore.

Have you read The Raj Syndrome by Subash Chakravarthy of Delhi University: A scathing indictment of colonial attitudes and self-deceptions about their role in India?

A new generation of Indian historians has become quite nationalistic.

I devote a hundred and fifty pages in the fifth edition of my A New History of India to nationalistic trends and the conflicts that have emerged.

But I haven't read that particular book.

There is considerable abuse of history in both India and Pakistan, for propaganda purposes.

I see this, and I regret it.

Unfortunately, whenever the truth is made malleable to a political dogma or a popular fashion or doctrine, it weakens and undermines the strength of a nation's intellect.

We can strongly adhere to what we believe only if we know the truth.

And history warns us of the mistakes of the past.

You suggest that Krishna Menon and others influenced Nehru deeply with their socialist, statist, even Marxist-Leninist ideologies.

But was there an option other than to build a powerful State given various fissiparous tendencies?

But it was necessary to build a strong central state, and I don't view Nehru's socialism in a negative way.

Except that he carried it too far: No foreign investment and the Regulation Raj.

Menon was a significant intellectual confidante; but he was close-minded and an ideologue, and his irrational attitude towards the US influenced Nehru, unfortunately for both countries.

We could have had a much more co-operative exchange of intellectuals and resources, given the enormous fund of mutual admiration and the ideals shared.

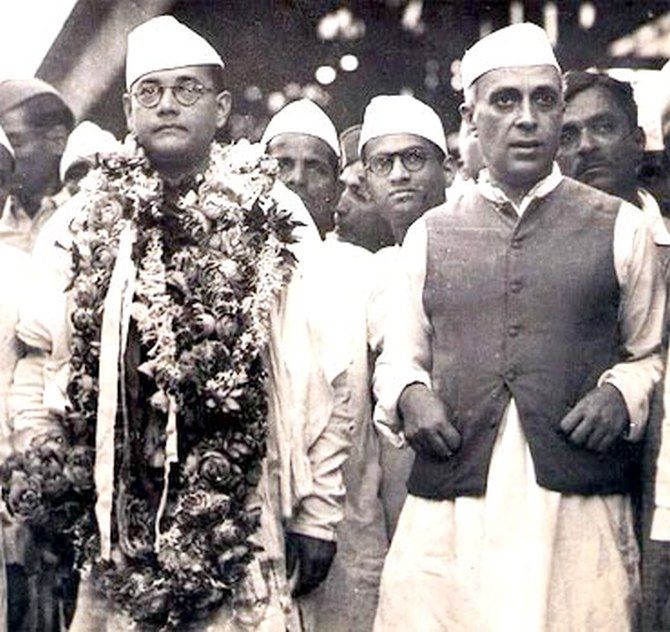

What about the recent 'rehabilitation' of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose?

Does this mean that the State is now more robust in its self-image?

I am glad to see Bose getting due credit.

He has been downplayed, for reasons that had to do with a World War II rationale, and a hatred of certain things that he did or advocated.

But he was an extraordinarily great and selfless leader, and his patriotism and his brilliance were second to none.

I deal with Bose sympathetically in my book, much against the prevailing dogma of minimizing his contribution.

You imply that Nehru had a false perspective of how religion worked in India.

You comment that he 'naively' believed that 'Europe has got ride of religion by mass education which followed industrialism... This process is bound to be repeated in India.'

Perhaps he had a simplistic view that certain aspects of development are universal.

He did not take into account the cultural variables and the religious pluralism.

It is naive to believe, as Marxists and some new historians do, that all conflicts in India could have been resolved with sufficient economic modernisation.

But despite his avowed agnosticism, Nehru did have a religious core to him.

That's part of his complexity.

You comment on a number of women who loved Nehru: Padmaja Naidu, Bharati Sarabhai.

Women liked him, and some hoped he would marry them; after all, he was widowed, he was charismatic, he was good looking and he was a great leader.

What do you think of Nehru's ability as a historian?

Are his Discovery of India and his Glimpses of World History any good?

He had remarkable intellectual range.

Having read Discovery and Towards Freedom, I would say he sometimes bent historical fact to an important political decision.

But that is neither surprising nor a fault: it made his history less accurate than if he had not been the leader of a nation.

What was Nehru's fatal weakness?

Was it his patrician contempt for the common man?

His somewhat exaggerated notion of his own stature as a world statesman?

His statist economics?

His blind faith in Communists and in China in particular?

His economic belief that planning was the solution proved to be simplistic.

He also had a romanticised view of China with all that 'Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai' a terribly sad mistake.

Another was his romantic concept of Kashmir as the homeland of his ancestors, and his resolve to defend and protect it, no matter how difficult or costly.

But he did not have contempt for the man in the street.

His charisma made him appealing to them, in fact.

Nehru's temper may have been seen as contempt, but he loved the common man; he had an affection for those not bred in the public school tradition.

He found their company even more engaging and appealing than that of intellectuals.

He was eclectic, and brilliant, yet had no false ideas of his own importance.

He even advised Indira about this, when she went off to Santiniketan.

Nehru was reared in the most aristocratic tradition and so he did have a certain snobbish concept of himself; but that gave him the courage to stand up to anybody, the British or others.

He had no false modesty; and he was like Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill: Of patrician birth and training.

The brotherhood/old school tie of Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge gave Nehru tremendous self-assurance.

He never felt inferior to any world leader, and he wasn't.

This helped India's image, and gave it a boost on the world stage.

As a historian, what do you believe the future holds for India?

Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

India's economic development is accelerating, which is very much to the good.

India is emerging from a time of insularity and is becoming engaged with the world at large.

Foreign policy has become closer to South East Asia and Central Asia and the world at large.

That is very beneficial.

If in fact Inder Gujral can follow up with an agreement with Pakistan to defuse the problems of Kashmir that could lead to a period of beneficial development to the subcontinent.

I believe the Gujral Doctrine shows maturity; it augurs well for this very important part of the world.

Twenty five per cent of the world's population can be at peace or in conflict.

I think it will be the former.