'Nehru remains central to the polemic between the Congress and the BJP, or stated ideologically, between secular and Hindu nationalism.'

'The reason is that Nehru represents what is optimally possible as a secular politics along with liberalism and democracy in a country like India.'

May 27, 2024, marks the 60 years since Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, passed into the ages. However, contemporary political discourse in India makes it hard to believe that the man died six decades ago.

Most recently, while campaigning for the ongoing general elections, Narendra Modi -- who is seeking a third straight term as prime minister, a feat only achieved by Nehru -- has been invoking Nehru to criticise the Opposition.

In the past 10 years, few of Modi's addresses in Parliament were made without a reference to Nehru.

The less said about the entire social media machinery put in place to malign Nehru day in and day out, the better.

On the other hand, those who are fighting to safeguard Constitutional principles also invoke Nehru's legacy and his role in guiding Independent India on the path of secularism and pluralism and, most importantly, to ensuring a strong democracy and the rule of law.

So, what makes Nehru so alive in our social and political dialogue sixty years after his death? And why are the 'changes' we see in 'New India' either welcomed or decried as a break from the Nehruvian past?

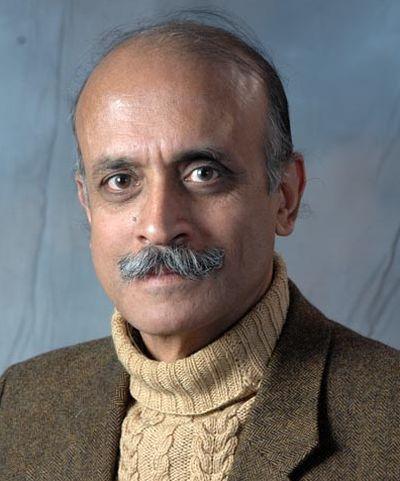

In an interview with Rediff.com's Utkarsh Mishra, distinguished historian Madhavan K Palat, left, bottom, answers some of these questions.

It has been sixty years since Jawaharlal Nehru's death. Indian politics and society have changed significantly since then. Yet, there continue to be debates which often refer back to 'what Nehru did'. Some give him all the credit for today's achievements while others put all the blame on him for today's failures. How do you see it?

Yes, Nehru remains central to the polemic between the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party, or stated ideologically, between secular and Hindu nationalism.

The reason is that Nehru represents what is optimally possible as a secular politics along with liberalism and democracy in a country like India.

Liberalism entails the fundamental rights of the individual citizen, and therefore of minorities. Democracy valorises the majority, which can lead to trampling on the minority. Any minority, be it religious, linguistic, regional, tribal, caste, or any other, may enjoy the fruits of democracy only through liberalism.

Hence the only acceptable form of democracy is the liberal one. This was a fundamental challenge to notions of democracy by pure majority.

If Hindutva is to make its case convincingly, through rational argument, it must refute Nehru, above all others.

But Nehru added two other arguments to this.

Unless the minorities could be included in the nation through liberal democracy, the unity of the nation would be compromised.

According to him, an anti-secular politics enabled the British to divide the country, with tragic consequences on so many fronts. This lesson must not be forgotten, he argued.

His further point was that the internal unity of the nation was essential to the external independence of the country, hence once again secular politics was unavoidable.

No other political leader was as uncompromising and unequivocal as Nehru on this range of issues, and nobody saw as clearly the manner in which they were inter-related.

There's a strong debate around Constitutional principles today and regarding the possibility of the current dispensation doing away with them.

Nehru is often criticised for bringing the First Amendment that imposed several restrictions on Fundamental Rights, though the civil liberties enshrined in the Constitution are also largely his legacy.

Does the proposition that the First Amendment was brought in simply to let the Nehru government have its way around the Constitutional safeguards and judicial scrutiny hold any ground?

The First Amendment was not introduced simply to pander to Nehru, not by any means.

Nehru, along with so many others, sought to guarantee rights and provide for social change. If the Constitution was an obstacle to social change, it was the Constitution that had to be altered, not the goal of social change.

The concept of amendment was thus built into the argument, and the Constitution was never meant to be rigid, inflexible, and sacrosanct.

He even argued in favour of easy amendment, through a simple majority in Parliament. India was urgently in need of social change, and at the top of his agenda was zamindari abolition and land reform in general.

When landed magnates blocked such reforms through court judgments citing fundamental rights, he resorted to amendment.

It does not follow that he undermined the Constitution, for, with or without him, others would have taken the same route.

It is a mistake to assume that judicial scrutiny alone protects the Constitution, for the good reason that judges can be suborned, and have been.

Further, democracy and a constitution can flourish without judicial scrutiny, as they have in Britain till recently.

The Constitution can be undermined only by the nature of our democratic politics, not through the Constitution itself.

Nehru upheld both the Constitution and democracy; both have been grievously compromised after him, but never by him and he was never the first cause.

Religion is now playing a more important role in national politics than it did a decade ago. In his autobiography, Nehru wrote that majority communalism is much more dangerous than minority communalism.

Someone witnessing the Indian politics today may find this view prescient. In contrast someone may take a view that neglecting 'minority communalism' may give more fodder to majority communalism.

Do you think that Nehruvian secularism was a bit too tolerant of minority communalism? Can we counter the influence of communalism in politics today with Nehru's views?

Nehru never used or was 'tolerant' of minority communalism. It was his policy to keep the State neutral while also ensuring that communities, whether majority or minority, did not violate the Constitution in letter or spirit.

But he did make an effort to ensure that Muslims in India, after the bruising experience of Partition, would feel secure in India.

The question of tolerating minority communalism did not arise. Some of his successors and others have however pandered to minority communalism in exchange for votes.

Therefore, following Nehru's own (not of others who speak in his name) democratic and Constitutional politics can go a long way to counter the influence of communalism in politics today.

We are in the middle of a General Election. Perhaps this is the first time that the Election Commission has issued notices to both the ruling party and the principal Opposition to 'refrain from making speeches on religious and communal lines'. We have been hearing the kind of speeches the prime minister has been making.How does this compare to the era of elections during Nehru's time, particularly when he declared 'an all-out war against communalism' during his campaign in Ludhiana in 1951-1952?

How did he succeed in popularising secularism and communal harmony among voters in a country that had recently seen a bloodied Partition on religious lines? And, by extension what lessons can our generation learn from the same?

The answer to this question is contained in my responses to your questions 1 and 3.

While we are on the subject of speeches, I should wish to discuss two of Nehru's most famous ones. 'Tryst with Destiny', which he delivered on the midnight of August 14, 1947, and the 'Light has gone out of our lives', his address on January 30, 1948, after Mahatma Gandhi's assassination.

While we are on the subject of speeches, I should wish to discuss two of Nehru's most famous ones. 'Tryst with Destiny', which he delivered on the midnight of August 14, 1947, and the 'Light has gone out of our lives', his address on January 30, 1948, after Mahatma Gandhi's assassination.

We know that the latter was delivered extempore. But is it true that the former was also not a written speech as the draft of what he actually wrote was lost?

If yes, then can you tell us more about the story behind it? How did Nehru go about his various speeches?

Nehru wrote his own speeches and he often spoke freely without a text before him; he did not use a speech writer. Hence, his speeches are uniquely his own and we can instantly recognise a speech which carries his signature but was written by somebody else, as occasionally happened.

He would also make drafts and depart from the draft as he spoke.

The first speech on the night of 14-15 August 1947 certainly exists in draft, and a facsimile has been published in the Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Second Series, volume 3, between pages 136 and 137.