'Over one million people served in various battlefronts during World War I. And yet, even today, we know so very little about them.'

'It is absolutely essential to acknowledge this part of India's colonial history,' Santanu Das tells Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com

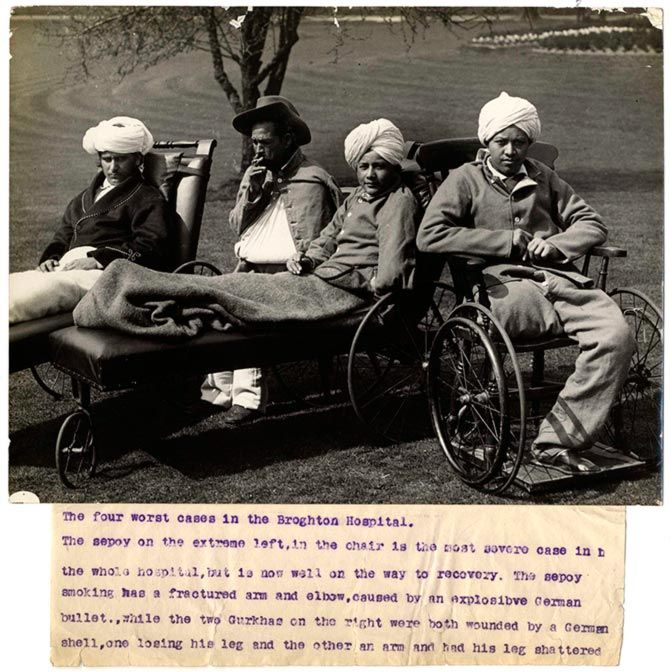

Photograph courtesy: Imperial War Museums

A little over 10 years ago Santanu Das, who teaches English at King's College, London, and whose fascination with World War I began with its poetry, started, on a whim, researching the Indian involvement in that war.

The sheer breadth of the statistics that confronted him was startling. And the attendant historical poignancy, of the duty India discharged for Britain, fascinating!

Das was hooked.

His examination of the Great War veered from poetry and became increasingly historical as he delved further and further into the lives of the brave, sturdy Indian soldiers who left Indian shores for distant and strange parts of the world to fight a war they had little understanding of.

They discharged their duty diligently and mostly with distinction, thousands of them dying far from home.

The result of Das's research is his most recent work, 1914-1918: Indian Troops In Europe (external link), a visual history based on rare archival photographs from Europe and India.

It was published in India by Mapin, January 2015, and will hit bookstores in the US and Europe September 25, to mark the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of Loos, the major last battle fought by the Indian infantry on the Western Front before they were transferred to Mesopotamia.

Das was educated in Kolkata and Cambridge and is the author of Touch And Intimacy In First World War Literature(Cambridge, 2006) which was awarded the Philip Leverhulme Prize and is the editor of Race, Empire And First World War Writing (Cambridge, 2011) and the Cambridge Companion To The Poetry Of The First World War (2013).

He is currently completing for Cambridge University Press a monograph titled India, Empire And The First World War: Words, Images, Objects And Music which formed the basis of a two-part series he presented for BBC Radio 4 titled Soldiers Of The Empire (external link).

Some of his archival material is showcased in a film titled From Bombay To The Western Front: Indian Soldiers Of The First World War (external link).

In an e-mail interview with Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com, Das describes, with a wealth of bittersweet details, the outstanding historical debt Britain owes the lowly but heroic Indian Sepoy:

DON'T MISS Part II of this fascinating interview.

How did you come to be interested in the history of Indian soldiers in World War I?

I was introduced to First World War poetry during my time at Presidency College, Kolkata.

It was while doing my first book, Touch And Intimacy In First World War Literature, that I became fully aware -- and increasingly disturbed -- by the enormity of the Indian involvement in the war and their erasure from 'Great War and modern memory'. That was in 2004.

I then researched and found out that four million non-white men were drafted for the war in the European and American armies; over a million of them were Indians. And yet, even today, we know so very little about them. I became increasingly absorbed.

It was about this time -- almost 10 years ago now -- that I visited the French Institute at Chandernagore in West Bengal and discovered the broken and bloodstained glasses of 'Jon' Sen, the only non-white member of Leeds Pals Battalion, who was killed May 22, 1916. It was a revelation; there was no going back.

What particular challenges do we face in trying to recover the Indian experience of the First World War?

The majority of the Indian soldiers were semi-literate or non-literate and did not leave behind the abundance of diaries, memoirs, poems or novels that form the cornerstone of European memory of the First World War.

Of course, we have the censored letters of the Indian soldiers: they were dictated by the sepoys to the scribes or occasionally written by the sepoys themselves, then translated and extracted by the colonial censors in order to judge the morale of the troops, and these extracts have survived today.

They are important documents, but are also problematic sources because of the process of mediation. Some of these letters are collected in a very helpful anthology by David Omissi (Indian Voices Of The Great War, 1914-1918).

In addition to these, we have hundreds of photographs of the Indian troops -- in trenches, fields, farms, billets, markets, towns, cities, railway stations, hospitals, prisoners-of-war camps. Though framed by the European gaze, they are some of the most eloquent testimonies and capture most vividly the daily texture of their lives. In the absence of substantial written documents, these photographs break the silence around them.

Indeed, this is what prompted me to compile these photographs from various archives in India and Europe (France, Belgium, Britain and Germany) for my visual history 1914-1918 Indians Troops In Europe. A selection of pictures from this book can be found at here(external link).

Why are the Indian soldiers forgotten?

After the devastation of the war, Europe naturally turned its attention to its own dead, wounded and bereaved; the colonial contribution, visible and acknowledged during the war years, became increasingly sidelined in the post-war years in the 'Great War and (European) memory'.

On the other hand, in India, the country's involvement in the First World War was immediately followed -- and gradually eclipsed -- by a general sense of betrayal and disillusionment with British rule, the anti-Rowlatt act demonstrations and the massacre at Amritsar (Jallianwala Bagh) in 1919 and the gradual rise of the anti-colonial nationalist movement under the leadership of Gandhi.

In post-Independence years, the nationalist narrative understandably supplanted and almost erased the country's participation in an imperial war. So the Indian contribution to the First World War gets written out of both the European and Indian narratives.

Yet, we are talking about the experience of over one million people who served in the various battlefronts during the First World War; it is absolutely essential to acknowledge their experience and this part of India's colonial history.

In 1914-1918: Indian Troops In Europe (Mapin, 2015), I focussed on the most visible group -- the ones who fought on the Western Front -- through rare photographs from various archives across India and Europe.

In India And The First World War: Objects, Images, Words And Music, to be published by Cambridge next year, I seek to weave together the first socio-cultural history on the subject.

India's involvement in the First World War cannot be confined to a narrow 'military history,' but has to be integrated into a much broader framework of cultural, social and political history.

However, to recover the Indian war experience does not, and in my view should not, involve any attempt to 'glorify' an imperial -- or for that matter any -- war or 'celebrate' the achievements of these soldiers. We are talking about traumatic events.

Moreover, these sepoys were the sentinels of the empire, let that be clearly acknowledged at the outset. Yet it is important to understand and analyse their involvement in the war without trying in any way to whitewash the ills of colonialism or falling prey to post-imperial nostalgia in any way.

Indeed we should try to understand the imperial war effort and the nationalist struggle in an expanded frame of reference that bears witness to the country’s complex and contradictory histories.

Photograph courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

What are some of the most interesting nuggets of history that you might have uncovered about the Indian soldier in WWI during your research?

I have been researching this subject for nearly 10 years now.

In the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, I came once across a page in the diary of an Australian private where an Indian soldier had signed his name 'Pakkar Singh' in Urdu, Gurmukhi and English.

The most moving artefact I found was a pair of broken, bloodstained glasses belonging to 'Jon' Sen the only non-white member of the famous Leeds Pals Battalion -- who was killed May 22, 1916. The discovery of the glasses led to a lot of media interest both in the UK and in India and to a short BBC documentary (external link).

A search through my extended family and friends in my hometown, Kolkata, revealed the war mementos of Captain Dr Manindranath Das: his uniform, whistle, brandy bottle and tiffin box, as well as the Military Cross he was awarded for tending to his men under perilous circumstances. Das was one among several distinguished doctors from the Indian Medical Services who served in Mesopotamia.

Over the years, I have had many such finds. I found this particular archival part of the research immensely moving: these objects are the mute witnesses to the war experiences of these men, the repository of what in my first book I call 'touch and intimacy'.

Approximately how many Indians fought in World War I?

Although I provide more detailed figures in my book 1914-1918: Indian Troops In Europe, here are some rough statistics.

Between August 1914 and December 1919, India recruited, for purposes of war, 877,068 combatants and 563,369 non-combatants, making a total of 1,440,437 recruits; of them, over a million, including 621,224 combatants and 474,789 non-combatants, served overseas during this timeframe.

These included the infantry, artillery and cavalry units as well as sappers, miners and signallers, Labour and Porter Corps, Supply and Transport Corps, Indian Medical Service and Remount and Veterinary Services.

Where did they serve? Which battlefields?

During the war years, undivided India (which would today comprise India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma) sent overseas seven expeditionary forces: the Indian Expeditionary Force A to Europe, IEFs B and C to East Africa, IEF D to Mesopotamia, IEFs E and F to Egypt and IEF G to Gallipoli.

In the course of the war, they served in almost all parts of the world -- from the mud-clogged trenches of the Western Front and the vast tracts of Mesopotamia to the tetse-fly infested savannah of East Africa and the shores of Gallipoli; they also served in East and West Persia, Palestine, Egypt, Salonika, Aden, Tsingtao and Trans-Caspia.

Indeed, to follow the routes of the Indian sepoy during the First World War is to trace its global course.

Photograph courtesy: Santanu Das

What parts of India did they hail from? And what strata of society?

In 1914, India had the largest voluntary army in the world.

But the men were recruited from a very narrow strata of its huge population, comprising largely the peasant-warrior classes spread across northern and central India, the North-West Frontier Province, as well as the kingdom of Nepal, in accordance with the prevalent colonial theory of 'martial races'.

A combination of shrewd political calculation, indigenous notions of caste and imported social Darwinism, it formed the backbone of British army recruitment in India.

It deemed that certain ethnic groups -- such as Pathans, Dogras, Jats, Garwahlis, Gurkhas -- were 'naturally' more war-like than others. These communities had often low literacy rates, were traditionally loyal and thus least likely to challenge the British Raj -- very different from the politically active and articulate Bengalis who were cast as 'effeminate' and barred from joining the army.

Of its 600,000 combatants, more than half came from the Punjab (now spread across India and Pakistan) which saw some of the most intense recruitment campaigns.

How many casualties were there and what happened to their remains?

It is difficult to provide a precise figure for the number of Indians killed and wounded in the First World War. Between 60,000 and 70,000 of these men were killed.

If one visits the battlefields of the Western Front, one comes across gravestones with their names and inscriptions etched in the appropriate language and carefully maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission -- not to mention the names of the Indians killed etched on the Menin Gate itself at Ypres.

One of the most moving places in the Western Front is the beautiful Indian memorial at Neuve Chapelle dedicated to the memory of the 4,700 Indian soldiers and labourers who have no known graves.

In the war cemetery in Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania (then German East Africa), I have seen huge memorial tablets with the names of Indian combatants and non-combatants, but not a single gravestone. However I don't know whether these men were cremated or the remains of these men were not found or it was decided as a matter of colonial (discriminatory) policy to commemorate them only on memorial tablet rather than bury them with individual gravestones (as with the white soldiers buried and honoured in the same cemetery in Dar-es-Salaam).

I understand that while the Indian soldiers, killed in Europe, were commemorated with individual gravestones, those -- particularly the privates -- killed in Mesopotamia and East Africa were denied such honour.

On the other hand, in Britain, where some of the wounded soldiers died, they were either buried in the Woking Cemetery or cremated at Patcham in the Sussex Downs, with appropriate religious rites.

In Iraq, the names of the Indian fallen are etched on the Basra Memorial. So the practice varied widely and it is difficult to pinpoint the exact impulses at work -- sometimes it was race, sometimes religion, sometimes it was where they died, and sometimes a matter of contingency and the whim of the local authority.

In 2011, I edited a book, Race, Empire And First World War Writing. (Noted social theorist and an expert on the cultural and social history of World War I) Michele Barrett explores some of these issues in the 'afterword' to the book.

And what happened to the families left behind in India?

Devastation presumably, as with hundreds of thousands of families around the world, but we do not know the precise details. Many of the families these soldiers came from villages dotted around northern and north-west India and the North-West Frontier province. They were non-literate and hence have not left memoirs or diaries or letters.

There's the extraordinary and immensely moving local tradition of songs of mourning sung by the village women which give us some insight into the grief and devastation the war caused across parts of North India, particularly in the province of Punjab.

The Punjabi poet Amarjit Chandan collected some of these songs. One of the songs goes (originally in Punjabi, here in Chandan's translation):

War destroys towns and ports, it destroys huts

I shed tears, come and speak to me

All birds, all smiles have vanished

And the boats sunk

Graves devour our flesh and blood.

A few years ago, I interviewed Punjabi novelist Mohan Kahlon in Kolkata. He mentioned how his two uncles -- peasant-warriors from Punjab -- perished in Mesopotamia, and how his grandmother became deranged with grief. In the village, their house came to be branded as pagal khana (the mad house).

- Part 2 of the Interview: 'The Indian soldiers adapted quickly and performed remarkably well'

If you have any Indian First World War anecdote, papers or objects, please feel free to contact Santanu Das at santanu.das@kings.ac.uk

1914-1918: Indian Troops in Europe, by Santanu Das will be published (external link) in the US and Europe on September 25, 2015, to mark the 100th anniversary of the beginning of The Battle of Loos, by Mapin Publishing in hardback.