'People are getting admitted to hospital two to three days before their death in a very serious respiratory compromise state and they are passing away within 48 hours.'

'Those who are coming early in the disease, the minute they are suspicious that they have COVID-19, the recovery rate has been much, much, higher.'

'The moral of the story is: We must destigmatise COVID-19.'

'People should be told: 'Look, if you have anything like this, please come immediately'.'

Dr Gudlavalleti Venkata Satyanarayana Murthy believes that every Indian needs to have ownership of their own COVID-19 situation.

Firstly, preventing the disease from coming to you is, largely, in your hands.

Stopping the wildfire spread of COVID-19 is a public duty of all citizens

The advance of the audacious virus has to be arrested.

Its transmission halted. In your home. In your apartment complex or street. In your locality. In your city. In your state. In India. In the world.

"People have to take ownership of using masks, maintaining physical distancing, and hand sanitation. It is in their own interest. If people do not realise that and put the blame on the system, if infection spreads, that is completely unacceptable."

Side-by-side, Dr Murthy points out, COVID-19 must be destigmatised.

If you feel you have caught this virus from somewhere, take charge of your life and test immediately!

And don't delay in getting supportive care or oxygen.

India's rapidly ascending death rate numbers look grim.

But given our population, a look at the casualties per million gives another perspective.

And it's slightly less scary. Especially if all people work together to avert the unnecessarily bold expansion of COVID-19.

A public health physician, Dr Murthy works both with the Public Health Foundation of India and the London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

He has driven a series of Indian and international projects to impede the community spread of a variety of harmful microscopic organisms for several decades.

Here's his interpretation of India's COVID-19 scenario and his best advice in the concluding part of an interview with Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com:

All eyes are on Maharashtra because it has such a large share of COVID-19 cases.

How is the state coping in your view?

Let's look at not just this pandemic, but even when we had the H1N1 swine flu outbreaks in 2009 and 2010 in India.

The four states which had the largest number of cases, even at that time, were Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Maharashtra had the largest number then, followed by Gujarat, even at that time.

Delhi did not have a major outbreak of H1N1 that time, but this time Delhi also has an outbreak.

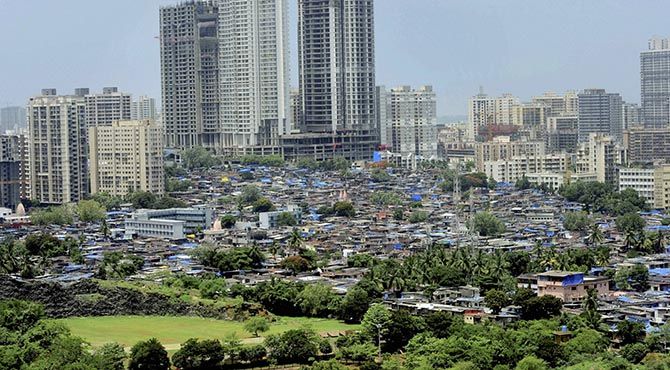

There are certain characteristics of Maharashtra which are very different from the rest of the country.

The population size -- it's a huge populated state with high population density.

It is one of the states with the highest degree of urbanisation in India.

Basically, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu have the highest urbanisation rates in the entire country -- more than 40 per cent of these two states are urbanised.

Nearly 50 per cent is getting urbanised.

There is the presence of some of the biggest overcrowded settlements like Dharavi slums etc.

This is very unique to Maharashtra, which is why you will find that these infectious disease outbreaks will always have a bigger footprint in a state like Maharashtra.

The nearest that you can compare Maharashtra to is Tamil Nadu on one side and Delhi, as a state, which is completely urban, on the other.

You will find that the trends are very similar across these three.

The disease did not start from our country. It's not indigenous. It has been imported.

Maharashtra, with Mumbai being the commercial capital, obviously has had a lot of people who have been travelling in and many of them have brought the infection, including the singer (Kanika Kapoor) who came from London, who was missed.

So, that is something which is very unique to Maharashtra.

Similarly, Delhi again, is a place where people enter the country. And then you have these big religious congregations from where people have moved out.

All these things have actually brought in a virus, which is not indigenous, into densely populated, poorly-aware population groups, which is why it spread so rapidly.

In terms of cases, Mumbai and Maharashtra, both because of its population and its characteristics would bear the first (and biggest) brunt.

You don't have international flights going to Bihar, which is why Bihar doesn't have a problem like Maharashtra.

How well is the state handling this huge burden?

As an expert looking in from the outside, what are some of the things that seem to be handled well and where does the state need to put its foot on the gas to achieve more?

I don't stay in Mumbai and I don't stay in Maharashtra. So, the ground reality is very difficult for me to comment on.

Definitely in terms of the measures they took, they followed whatever was recommended by the Government of India, by the WHO (World Health Organization).

They did not develop their own independent protocols.

They had their protocols in place, which have been adapted, and they started off with the lockdown (in India) and Maharashtra still continues with lockdown in many areas, compared to many parts of the country.

So, they have had all that in place.

They have had the process of contact tracing. The protocols have been there.

I don't know, sitting outside the state, how effectively, how seriously has the implementation of the protocols actually happened.

So, if I have to look at something like contact tracing did the ANMs (auxiliary nurse midwife) really go to the house, ask the questions, record them properly -- that I would not know from outside.

Those are some of the things, the small things that make a big difference.

The most important thing is contact tracing effectively, to identify cases early on, so that we do not have complications and do not die because of COVID-19.

The entire chain can be broken if you have serious, efficient health workers doing their job.

On Worldometer one looks daily at the case and death count of all the different countries.

India has such a huge population.

If India's case count and death count were to go even higher, compared to other countries already on the list, in proportion to its population, it will not be that high actually?

Absolutely.

Whenever we compare, we always look at a common denominator.

You can't compare Uttar Pradesh with Telangana, because the populations are very different, which is why we use either a per 100,000 or per million population as the denominator.

The minute we use per 100,000, or per million population measure as the denominator, we find that, we, as a country, are very similar, in our case per million, or deaths per million population, with our neighbours.

In fact, we are doing better than Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Pakistan has 8 per million deaths. And Bangladesh has 7 per million population deaths.

We are at about 4 per million deaths, which is what Singapore reported -- 4 per million.

New Zealand is 4 per million! Malaysia is about 6 or 7 per million.

We, in terms of our death rate, have been able to keep a profile which is very similar to other countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

I don't think any of the countries in Europe have had these low case rates or death rates.

I'm not saying it is because of our health system or because of a government system.

Let us just say that we've been lucky enough that it came later to India.

Maybe the virulence of the strain was lower and the conditions that we have, the climatic conditions, may not have allowed the virus to thrive in the open. All these could be factors.

Do you think that Indians are slightly more asymptomatic?

Could that be a reason too?

It's just the same. About 80 to 85 per cent people are asymptomatic across the globe.

But asymptomatic nature doesn't (affect) the death rate.

What leads to a higher death rate is lack of early identification of a case. And then lack of provision of supportive care.

For all the deaths that we have seen in India: People are getting admitted two to three days before their death in a very serious respiratory compromise state (deterioration in lung function) and they are passing away within 48 hours.

Those who are coming early in the disease, the minute they are suspicious that they have COVID-19, they have been tested and they are early in the disease, those people, the recovery rate has been much, much, higher.

The moral of the story is: We must destigmatise COVID-19.

People should be told: 'Look, if you have anything like this, please come immediately. Go to your nearest health provider and get a check done'.

We must provide testing, at least for those people who have symptoms, forget the entire population.

Those people who have symptoms they should be tested.

They should not be running from one hospital to the other to get testing.

They should be tested early and we provide them immediate hospitalisation to see that the complications do not occur and provided oxygen supply.

We don't need ventilators that much in India.

We need oxygen supplies.

If we are able to provide adequate oxygen, we should be able to reduce the deaths.

Why do you say we don't need ventilators that much in India?

If you look across the country, less than 1 per cent of the COVID-19 cases had to be put onto a ventilator.

The clinical admissions that we have had across the country, less than 1 per cent needed ventilation, whereas 15 to 16 per cent needed oxygen support.

We have to ramp up our oxygen support.

If I look at Maharashtra, each of the (sub-centre) hospitals we must have an oxygen set up.

People can't have to travel too far for oxygen.

We must try and have smaller hospitals (in the districts) with oxygen and supportive care available. Not ventilators.

For ventilators they can go to Mumbai, Nagpur, any other place.

But some of the smaller places must have oxygen, for sure, to prevent mortality.

In your view, as an authority on public health, now that lockdowns are easing: What do we have to be extremely careful about so that there isn't a sudden spike?

Possible to summarise the measures the country needs to make as its COVID-19 policy and the points of caution?

Most important is that the prevention of transmission of disease is an individual responsibility.

People have to take ownership of using masks, maintaining physical distancing, and hand sanitation. It is in their own interest.

If people do not realise that and put the blame on the system, if infection spreads, that is completely unacceptable.

What is essential for the government and the health systems to prevent is serious complications and death.

If the death rate increases, it is the responsibility of the government health system and other health systems.

But if infection increases, then it is individual responsibility

Just like you know, our Constitution gives us the freedom of speech. That does not mean you can speak anything.

Similarly, opening up the lockdown has given us the freedom of going back to work and looking at some leisure moments in terms of meeting up with your close relatives.

Then you must see that you do not enhance the potential of the infection being transmitted by your personal hygiene method.

There is nothing better than physical dispensing.

The virus is not floating in the air, waiting to attack somebody who is just coming in front of it.

It is only being spread from somebody who's infected, bringing out the virus in the cough, in the sneeze or even when they are talking through salivary particles.

You can socialise but keeping that distance would be most important.

Has the government, according to you, done a good enough job in educating the people in carrying out their individual responsibilities?

In terms of mass media approach, I think plenty of awareness has been (created); which is available across media.

I think, for changing behaviour, interpersonal associations are more critical.

It has to be the ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist or the trained female community health activist), the ANM, who has to be convinced, and then she/he go on to convince the people whom she or the health worker deals with.

Now that needs to be strengthened more.

There have been efforts in training frontline health workers, but I think that needs to be emphasised more.

There has been a lot of mass media campaigns, but for people to change their behaviour, especially health behaviour, they depend upon somebody they trust, which is the ANM or the ASHA, who is working with them or their family doctors whom they meet.

So inter-personal channels have to be strengthened a bit more than what it is at the moment.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, various epidemiological studies predicted huge, huge numbers for India.

Can that still happen later down the road or were those over estimations?

What people did initially was, take the example of Italy, Spain and then extrapolate that to India.

The problem with that was, Italy and Spain their above-60 population is 27 to 30 per cent. Italy, I think, is 26.9 and Spain is about 29 per cent.

Our population above-60 is only 9.3 per cent. We are way off.

The highest risk for cases and deaths is for those above the age of 60 -- especially deaths. We have a very low proportion.

So, when we extrapolate the Italian or Spanish trends to India, your results would always be on the higher side.

The other thing we have to consider is that, except in the urban areas, where there is higher population density, 70 per cent of our population is rural, where the population density is very low.

People are not overcrowding; they have adequate space.

The effect of temperature, climate and humidity on of the virus' viability -- people did not look at all that, when they looked at the initial models either.

The models developed later, by scientists in Singapore, they are very close to what we have seen now.

We are doing very similar right across South Asia and Southeast Asia.

There's a lot of similarities in the way we are functioning.

We had to take all of these things into account -- our demographic profile, our population density, our mobility.

A lot of us, except in the urban areas, do not use public transport -- whereas in Rome or Paris or London or New York it is only public transport, where people are coming into close contact.

Extrapolating from those into India would not be the right way to do it.

We have to find our own assumptions before we model and that's where I think the initial models were way off.

One keeps hearing that India's data on COVID-19 cannot be trusted. Why not?

What is your refutal to that?

IMAGE:Dr Gudlavalleti Venkata Satyanarayana Murthy

IMAGE:Dr Gudlavalleti Venkata Satyanarayana MurthySo, you are in Mumbai. You have the Bombay Stock Exchange in Mumbai. Every day there is trading happening on the stock exchange.

Are those figures of the share market, are they true? Are they untrue? Are they biased? Are they unbiased?

It is very difficult.

We have to plan based upon whatever data is available in the public domain.

If there is more data that is available in the public domain, it will actually improve the planning.

Whatever data is there, it has to be used and that is the way we have all been functioning, whether it is looking at the death rate or the case rate.

It's all based upon whatever has been released.

Each state has had its own testing policy.

Some states are not testing at all.

Some states are testing a large number.

When you test a large number, you will find more cases.

That is good because it tells you that these people were infected.

If you don't test you do not know how many people actually have the infection.

Which are the states that are not testing or not testing well enough?

Oh, there are plenty!

I would not like to take names. But there are plenty.

You could just look at the list and you will find them all over there.

(As per data courtesy ThePrint graph the lowest testers per million, last month, were Bihar 452 pm; Telangana 649 pm; Jharkhand 976 pm; Manipur 626 pm; Uttar Pradesh 875 pm; Mizoram 258 pm; Chhattisgarh 1,433 pm, Meghalaya 1,047 pm)

The most important thing: In terms of the statistics, in terms of the data, we may be testing less, so the case load may be low, but when it comes to deaths, it is highly unlikely that deaths would be hidden, especially when you have COVID-19.

I would be very happy looking at the trends in terms of death rates. And that is what many of us are tracking, because that is the ultimate.

If a person has died, it's highly unlikely that the cause of death would be covered.

It could be some sort of a mis-classification. So. if I'm a diabetic and I die of COVID-19, I may be reported as a death because of diabetes rather than COVID-19.

But that is the only semantic difference that may occur.

Otherwise, generally deaths would not be missed.

Looking at deaths as a trend would perhaps be the best way to go forward.

But if you look at some of the figures internationally, like Russia, you wonder how they can have so many cases and so little deaths.

So internationally, some countries may be doing just that -- suppressing deaths.

Yes. You scan through, and you see Russia. Or Indonesia.

I don't even know about Sri Lanka. It could be that they being islands, so they have been more insulated. Indonesia too.

But our figures in India, our initial spike in a state like Telangana came from Indonesian preachers who had come to Telangana.

We don't know whether figures that are reported globally are really true.

Yes, most of it, that you get from Western Europe or from the US, is -- they have the national systems and that data is very accurate.

Russia: Whether the extreme cold is something the virus doesn't like -- I don't know -- which is why they may have reported less cases.

But in recent days, for last two to three weeks, Russia has been reporting more and more cases and deaths than what they did in the first few months.

That is more about governmental policy in different countries.

Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com