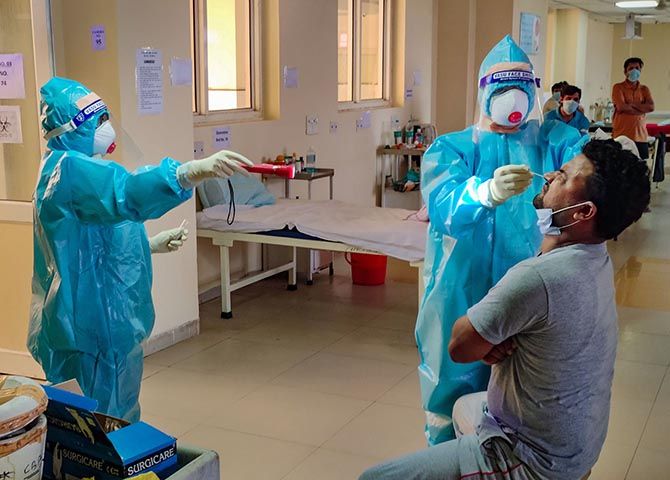

'Strengthen hospital capacity, look after patients who need care, primarily ICU care...'

'Train doctors, get PPE, get ventilators, have treatment protocols in place.'

The Indian Council of Medical Research in New Delhi is responsible for much of India's COVID-19 strategy.

How long shall the lockdown be for?

Should it be extended further?

How should India function after lockdown and what differences in daily life need to be instituted?

What are the treatment guidelines for this virus infection?

What are the case projections now and post-lockdown?

What kind of containment policy should India have post-lockdown?

And much more.

It advises both the central government and state governments.

The ICMR, in turn, is guided by several task forces.

Dr O C Abraham is a senior member of the clinical research group, a medical task force that counsels the ICMR.

An expert in infectious diseases, he is the professor and head of the department of one of the units of internal medicine at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu.

This disease specialist did his postgraduate training from Vellore and his Master's in public health from University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and fellowship in infectious disease from Wayne State, Detroit, both in the USA.

Dr Abraham offers Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com a long-term, cautious view for India, as it confronts and overcomes the COVID-19 pandemic. The first of a multi-part interview:

Why is India's graph not like the other 'normal' COVID-19 graphs?

The India graph has not had the very rapid escalations, so far, that one saw for Italy or Spain or America.

Its graph is not showing the patterns of a lot of other places yet.

What is your view on that?

The number of cases may be low - maybe artificial -- because we are not testing like lots of other countries are doing.

Not testing like South Korea is doing, Singapore is doing or Iceland is doing.

That may be one reason.

The other is the virus came into India much after the other countries.

Then maybe all the measures we adopted have helped us to 'flatten the curve'.

Maybe we will see a slow rise and a less-taller peak.

That's what everybody is hoping for.

This is a novel virus.

That means all of us are susceptible.

None of us are immune.

Highly contagious.

The experience in other countries is that you have a very rapid rise or surge...

It looks like, till now, whatever measures we have adopted, we are not seeing that kind of rise.

So, that's been a good thing.

We don't know what the future holds.

Hopefully, as the lockdown is released, in a gradual fashion, maybe we will build up this concept of herd immunity and protect our most vulnerable.

And maybe we will not be witness to scenes like we have witnessed in other parts of the world.

That's what we are hoping for.

IMAGE: Dr O C Abraham

IMAGE: Dr O C AbrahamWhen COVID-19 first arrived, we watched its rise in China, and then the way it galloped furiously through, first Italy and then Spain.

Later it surged ahead in America with a staggering nearly 1.3 million cases (as of May 4).

And there's no comparison there.

They look like two different diseases.

Why has it been so different country to country?

Several reasons.

One thing could be the demography itself.

It could be coexistent serious medical conditions, which have made the patients more vulnerable.

Maybe it is the way you are classifying the death, as due to coronavirus.

Or maybe (because of) your testing policies.

Maybe genetics.

I have not seen any work on it, only a postulate.

The influence of age and another underlying serious medical condition, can have a really bad impact on patients coming in (contact with this) virus.

According to one source, each country has to do an evaluation of the mortality and morbidity of COVID-19 in its people, as soon as possible.

If the indicators are on the high side, a longer lockdown, more aggressive case identification and preparation for many more hospital beds is suggested.

But if the morbidity and mortality indicators are more like a flu or other ordinary viral infections, the lockdown can be lifted in a graded manner and there should be a strict continuance of a proper hygiene and distancing regimen.

Which category are we in exactly?

We are still in -- as the phrase goes -- in the fog of the pandemic.

Everything is hazy now.

We don't have good data.

When you look at mortality rates, for not just COVID-19, influenza, everything, you should look at both the numerator and denominator.

See (for example) an Italian gentleman, who is 85 years old, has diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

He also gets COVID-19 and he dies, unfortunately.

Are you saying that he died of coronavirus or with coronavirus?

It is a good question to ask.

We saw this in the 2009 influenza pandemic (the swine flu outbreak from January 2009 to August 2010).

When they started to trace the fatality rate -- that means you died due to this influenza pandemic, ie you are a case among all the cases -- they said it is a very high number, 5 per cent.

But finally, it was some 0.1 per cent or something, an extremely small number.

So, people have estimated that -- there's a publication from this group in Imperial College in London -- the infection fatality rate.

The numerator is everybody who gets COVID-19 infection; some don't even have symptoms, they may not even come to medical attention because the illness is so trivial (and the denominator is deaths).

The infection fatality rate is way below 1 per thousand, 0.145 per cent, a number something like that.

Each country should have a good assessment of their infection fatality rate. Less ideal would be the case fatality rate.

If you look at Iceland: Iceland went into the general population and tested everybody there.

Their mortality rate is 0.5 per cent.

That is closer to the infection fatality rate.

The absolute risk of dying is very low (in Iceland).

So, what should India do now?

India should on one side: Continue its efforts at lockdown, social distancing, stringent hand hygiene, cough etiquette and everything.

On the other side: We should also get our hospitals ready for the second wave.

That is, strengthen hospital capacity, look after patients who need care, primarily ICU care, ventilation and things like that.

Train doctors, get PPE, get ventilators, have treatment protocols in place.

Remember this virus spreads very rapidly and efficiently from an infected to an uninfected person.

Most people have only mild symptoms.

Even when you have not yet developed symptoms you can transfer COVID.

Aggressively testing, finding cases, isolating them, tracing contacts and quarantining them, will go only a certain extent.

Korea has managed to do it to some extent.

Kerala maybe.

But you're all worried about the so-called second wave.

Let's all hope and pray that it doesn't happen.

But in case we have a surge, like what we saw in New York or Wuhan or Lombardy (Italy), we should be ready for that.

America's confounding surge may be as you mentioned because a lot of the population in America does have some of these comorbidity issues.

In India also has that in urban areas.

But generally, our population doesn't have that much comorbidity.

Would you agree or disagree?

If you are less than 65 and you do not have any major medical problems, your absolute risk of dying from this infection is extremely low.

There is a (recent) peer-reviewed publication, which has looked at mortality, ie the absolute risk of dying from COVID-19 infection in Europe and cities in the US, in New York.

It is something like 70 -- I might not be exactly correct -- per million.

If you are less than 65, your absolute risk of dying is 70 per million.

So that is a very small number.

For most people who get this virus infection, it behaves like you had a mild attack of flu.

But if you are an older individual, have significant medical problems, everything from obesity to chronic lung disease or chronic heart disease, you are a sitting duck.

In India, we have a lot of that in the urban areas, but the general population is quite healthy and tough?

Isn't that true?

Being healthy is not just the absence of disease.

People of poor socio-economic status, (lack of) access to medical care. Smoking, you know, is really bad, all those kinds of things -- it is not just that you have a diagnosis of diabetes or heart disease.

Those from poorer (backgrounds) don't have access to a lot of things.

That can also contribute to increased mortality.

What we have seen in the US, in New York, a lot of people are homeless, who are dying, minorities in the US, the blacks, the Hispanics, Asians.

Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com