'If our body is able to mount a very successful immune response, we can negate the virus.'

What the world knows about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can be written up on a tiny postage stamp.

Even now, more than a year later, we know very, very, very little.

Doctors and scientists uncover something new every day.

Professor Rajesh Khanna and his team, at the University of Arizona Health Sciences' College of Medicine, have fascinatingly discovered that the COVID-19 virus has the unique ability to mask pain.

His words: "The virus showcases its sneaky brilliance by fooling you and giving you pain relief."

In Part II of his interview to Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com, Dr Khanna explains why pain protects the body.

And how by blocking the pain, COVID-19 gains more ground, affecting more people and increasing rates of transmission.

There is this the connection between smoking and the ACE-2 receptors and about how smokers had more ACE-2 receptor production and therefore, they were more at risk of getting COVID-19.

Now, if people, for some reason have more neuropilin-1 are they more at risk?

And is that possible?

Is it possible to have more neuropilin-1 for some odd reason?

It is.

The activity of the neuropilin-1 gene is higher in biological samples from COVID-19 patients compared to healthy controls and the activity of the neuropilin-1 gene is increased in pain-sensing neurons in an animal model of chronic pain.

So yes, the neuropilin-1 protein itself can go up.

Just like when people who are smoking have higher ACE-2 levels and they are more susceptible to COVID-19, so the same can be envisioned in this case.

And when we have access to patients that suffer from COVID-19, we can begin to ask that question, is neuropilin-1 higher in that patient?

So, it's very possible that neuropilin-1 will also be higher in these asymptomatic COVID-19 patients which then translates into them having pain relief.

Based on whatever knowledge that you have of viruses, what is crucial about the spike protein to the virus?

I mean, does it help latch on to a new host or is there something important about the spike protein?

No, the spike protein is pretty common to a lot of viruses.

Basically, it's a lock and key kind of system.

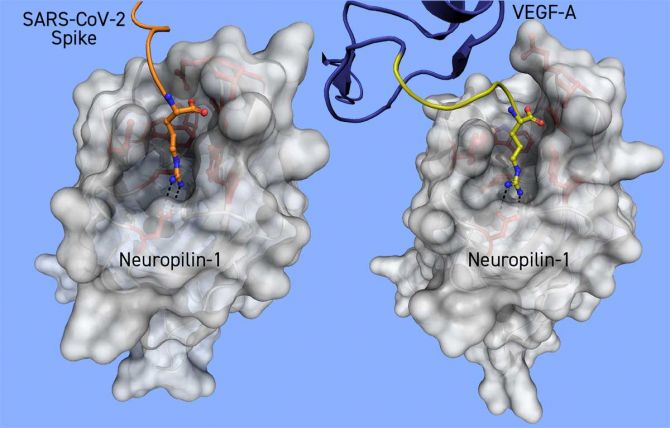

The virus has the key -- the spike protein that needs to find the lock (for example the neuropilin-1 receptor) on the host cell.

In another way, the spike protein of the virus is like a postage stamp that can be used to send it to an address -- in this case the neuropilin-1 receptor.

Just to understand this better, will a more contagious virus definitely have a spike protein, because it's a better mechanism?

Almost every virus has a spike protein, whether they're more contagious or less contagious -- I think it's irrespective of that.

The virus has to get in somehow.

And the spike protein has the signature to let the virus in through surface receptors on a host cell.

But this COVID-19 virus is very clever and can mutate.

And quite rapidly too.

From almost the very beginning, there was a mutation discovered in SARS-CoV-2, the D614G mutation that made the virus more infective.

Initially found in about 20 per cent of people, D614G mutation is now the dominant variant in the global COVID-19 pandemic.

So, the virus completely mutated itself in under nine months, and made it much, much more infectable and also it reproduces more too.

You seemed to have happened upon the connection between neuropilin-1 and the COVID-19 virus because you were exploring the asymptomatic nature of COVID-19.

If one thinks about it, the asymptomatic nature/side to COVID-19 is very, very interesting.

Has there been any other aspect that you sort of uncovered about the asymptomatic nature of this virus that that you would like to share?

Indeed, the pain resilience offered by the virus has been an unexpected outcome.

Likely, there are many as yet not discovered functions that will be revealed in time.

Going forward we intend to try to figure out if an immune response mounted by individuals in response to the virus is perhaps a little bit more subdued in the asymptomatic cohort than those that get full-blown level COVID-19.

So, I think this will also offer some insight into how our bodies, how our immune systems are able to handle the viruses, right?

Because ultimately, if our body is able to mount a very successful immune response, we can negate the virus.

Somehow in the asymptomatic cases that's been dampened, which could also explain the masking of pain.

Your lab focuses on pain research I understand, and you were already studying your neuropilin-1.

What was the reason why you were studying a neuropilin-1?

Also does this finding you have made tie up with any other pain research being done elsewhere?

We got into neuropilin-1 because over the past decade we have been working on a signalling pathway involving ion channels that contribute to pain generation and maintenance.

These ion channels are 'tunable' by many proteins, one such protein that we found that can 'tune' the function of ion channels resides within cells and is called CRMP-2 (collapsin response mediator protein 2).

Now, CRMP2 is a protein that we've been working on for the past 12 years or so.

CRMP2 protein talks to the ion channels which regulate pain.

We became interested in neuropilin-1 because if you engage or kickstart neuropilin-1 you eventually signal to CRMP2 and this relay system then tunes the ion channels that play a role in pain.

So that's why we were studying it.

As far as other labs working on neuropilin-1, to our knowledge nobody's working on neuropilin-1 in the context of pain.

In the context of cancer, neuropilin-1 has been well studied for the past 20 plus years or so.

A role of neuropilin-1 in the immune system is also beginning to be understood.

Why does a virus trigger pain in the first place?

How does pain contribute to the healing function in the body?

Obviously, you would only feel pain if the body had some advantage in feeling that pain.

So how does it help heal?

Okay, well, that's a that's a great question.

How does pain help heal?

Pain, as you can appreciate, is an early warning indicator.

If we didn't -- if you and I didn't feel pain -- we would be in a lot of trouble.

You can imagine any scenario where you hurt or injure yourself.

Well, you are going to remember that -- there's going to be a 'memory' of that pain and this memory is going to prevent you the next time you are in that situation, from doing the same thing.

In this case, the virus (the COVID-19 virus) showcases its sneaky brilliance by fooling you by giving you pain relief so you're not going to remember this, because it's not painful.

In this case, it is working in the opposite way.

If there is an injury that is going to make me or you feel a lot of pain and you're gonna say: 'Okay, I'm going to try and avoid that'.

But in this case, it's doing the opposite, which is advantageous for the virus and not for you.

So here we are attempting to figure out why the virus is not causing pain until it is in the symptomatic stage.

With any flu you have myalgia or body pain and aches and, of course, a lot of other very bad things.

Definitely, if you have a fever or flu -- I'm sure you feel the same thing in India as I feel here in the US -- you have body aches and fever.

But that that pain is different.

That pain is generally difficult to avoid but you will try to make sure that if a colleague or somebody has a flu, you're going to try to avoid them, because you remember the pain that you had from flu when you accidentally contracted it.

But in COVID-19, it is actually causing you pain relief.

So, it's different.

When I interviewed Dr Ravindra Gupta, who works out of London on HIV and now SARS-CoV-2, he was telling me about how they're using pseudo viruses for their study.

Now you just told me about how these people had a reduction in pain when they had COVID-19.

Wouldn't there be some use in creating pseudo viruses that can act like non-harmful versions of the COVID-19 that would help in pain relief?

Absolutely.

A pseudovirus seems like a great idea.

With this kind of 'naked' virus, you can strip down the virus such that it doesn't allow its replication, for example.

Its ability to replicate makes it a competent, and therefore, a dangerous virus.

The pseudovirus may retain elements that are required to produce pain relief -- but this remains to be tested.

Would you sort summarise the significance of your finding -- of the action of the COVID-19 virus on neurpilin-1 that causes a person to be asymptomatic and not feel pain -- and put into perspective how important this is for further pain relief research?

So, there are three main things we have learnt from this virus.

First, the virus has bequeathed us the gift of pain relief.

But this so-called gift comes at a high price because it allows the virus to infect a greater number of people.

The second thing that the virus has revealed to us is a potential new target in managing chronic pain.

This new target is the neuropilin-1 receptor.

And if we can deeply understand how neuropilin-1 controls pain signalling, then and only then can we begin to target it at a molecular or protein level, to design ways to block pain.

The third thing emerging from our studies is how our findings may be relevant to not only COVID-19 but also the opioid epidemic.

For a number of years now, the United States has been mired in the opioid epidemic.

Now, with COVID-19, these global health events are colliding -- the pandemic and the opioid epidemic.

Healthcare in pain is fractured and pain management for chronic pain patients has been even more difficult with social distancing rules and reduced face-to-face doctor visits, and evidence suggests that opioid use may be even higher than in earlier times.

Therefore, our findings have implications for both of these global health events: the virus has presented us with neuropilin-1 as a potential new target for chronic pain that may result in a new non-opioid for chronic pain.

These compounds can also slow down the entry of viruses, so they can also be effective against COVID-19.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com