'Chetan Bhagat is not great literature. Is that like you write third rate books and people can't do much better than to read those third rate books. Is it really an achievement?'

When he published his first book, Stranger to History: A Son's Journey through Islamic Lands in 2009, V S Naipaul hailed Aatish Taseer as 'a young writer to watch.'

His latest novel, The Way Things Were -- the fourth one he has written -- has received much acclaim.

Like his mother, well-known Indian journalist Tavleen Singh, Taseer has worked as a reporter. His bylines have been published in Time magazine, The Sunday Times, The Sunday Telegraph, The Financial Times and Esquire.

Taseer divides his time between London and Delhi, which he says is an 'amazing city to work in; the months roll by like hours and days, the books get written'.

He has a birth connection with Pakistan -- his father, Salmaan Taseer, the governor of Pakistan's Punjab province was assassinated in 2011 -- 34-year-old Taseer minces no words when he talks about India's worrisome neighbour.

Neither is he sparing when it comes to smaller matters like, say, literary festivals or Chetan Bhagat, discovers Nishi Tiwari/Rediff.com

Have you read Part 1 of the interview? 'Sanskrit had become more a symbol than a language'

You were at the Times Literature Festival (held in Mumbai in December 2014) to promote your new book. What was the experience like?

People were very, very curious about the use of Sanskrit in the book and were very receptive to the discussion we had.

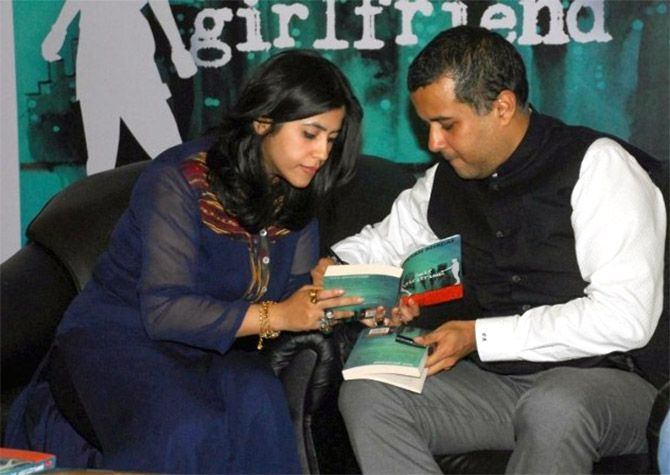

Photograph: Chandra Mohan Aloria

You must have been to the Jaipur Literature Festival as well?

I've never been there. I don't go on principle, lots of us don't. I feel the festival practises a sort of a bias between local writers and foreign writers.

There's a lot of glamour attached to one and the other is dealt with rather patronisingly. I know that (Arvind) Adiga, (Ramchandra) Guha, (Amitav) Ghosh, among others, don't go there either.

Nobody sat down and made this decision together. It's just that we all got the same feeling about the fest.

With Guha it was a horror story -- William Dalrymple sort of hinted that he would write a review if Guha attended. Guha was so furious he didn't respond to the mail and Dalrymple killed the review.

With Guha it was a horror story -- William Dalrymple sort of hinted that he would write a review if Guha attended. Guha was so furious he didn't respond to the mail and Dalrymple killed the review.

Salman Rushdie doesn't have many kind things to say about it either. They are very, very cowardly.

That one time when (Salman) Rushdie couldn't attend -- come on!

Are you really saying that you couldn't have stood up to that pressure and actually had him there?

These people can't talk about freedom of speech if give up so easily. Firstly, there the Congress was in power. Secondly, you had the media's support. Everyone would have sided with you. You do nothing.

You didn't even have the courage to have him participate via video.

What do you think of lit fests in general?

I'm not a huge fan. I read books all the time, but I don't really feel the need to meet the writer.

According to me, writing is a very nice and symmetrical process that happens in solitude and a person then reads it in solitude. That's the relationship. But it's become such a culture now, these literary fests.

You know that New Yorker cartoon where two people are deserted on an island and one of them asks, 'What should we do,' and the other one says, 'Let's start a literary fest.'

It's become a thing you can't really put back in the box. If I told my publisher that I wouldn't do any lit fests, he'd be pretty irritated with me.

So you attended the Times Lit Fest because it coincided with the release of your new book.

Exactly. I actually like this festival; I've done it two times and I like the way it comes together.

It has its moments of chaos, but it has a nice mix of people. The audience is wonderful here -- it's really a pleasure to have a city's audience come and ask you nice questions.

And Bombay in that regard has a very nice culture, like Kolkata.

The protagonist of The Way Things Were, Skanda, inherits Sanskrit from his father...

He also inherits a sense of grief about the story of his father. Sanskrit becomes a way to deal with it for him.

But it also keeps him away from life. And a part of the course of the book is him finding a way to live again.

Like your protagonist from The Way Things Were, did you inherit something from your father, the late Salman Taseer?

The only thing he passed on to me was his DNA.

What do you think of India's current literary scene?

I don't think about it.

And Pakistan's -- there have been quite a few formidable writers in the recent years like Mohammed Hanif, Mohsin Hamid, Daniyal Mueenuddin?

I like them.

What do you make of Chetan Bhagat, considering he's often credited to have gotten more and more Indians to read through his books?

I don't know. Is it that you write third rate books and people can't do much better than to read those third rate books? Is it really an achievement? What is the achievement exactly?

We can't count Chetan Bhagat as an airport novelist. He's not an airport novelist -- he apparently writes about important, relevant things.

In other countries when they are having kind of a moment in which they are writing about significant things, you see some great literature come out.

Chetan Bhagat is not great literature.

So maybe, like, the Indian moment is not such an exciting moment. I mean, he represents an extraordinary phenomenon where he's writing about things everyone wants to read about.

The material is good, he writes in a language that everyone can read but no one wants to read them outside India.

I think that should say something. When Russian literature was at its height, people couldn't translate it fast enough. It's the same today with Chinese literature.

You were talking about the Pakistani novelists; they have found audiences. Chetan Bhagat doesn't find an audience because no one outside India can read him.

He might just be a symptom of the fact that in English, India is basically a semi-literate country and Chetan Bhagat is the best it can do.

It doesn't seem to me that we need to look for a deeper explanation.

Do you have any favourites among Indian authors?

I have many. I can't call V S Naipaul an Indian writer but I have great admiration for his work. I like Kiran Nagarkar very much. I like some of the early Rushdie a lot.

I like, when I think of my contemporaries, Manu Joseph's work. I like Neil Mukherjee's work. Rahul Bhattacharya. (Amitav) Ghosh has made a big body of work.

Indian writing is very diverse. There's a lot that you can get into.

I just read Deepti Kapoor's A Bad Character that I liked very much. It's a super urgent, strong book about Delhi -- the city I live in. I was surprised by that book. I was surprised by the way the city looked and felt in that book.

How much does a sense of belonging, or the lack of it, contribute to a writer's sensibility? How do you think it has shaped your own writing?

For me, it's everything -- that deep engagement, sometimes fraught, sometimes tender, with Place.

People say we live in a world where Place doesn't matter anymore; I feel that, for all the reasons they think it doesn't matter, it matters immensely.

It's like culture or history; one needs it even more when it wears thin.

The West, which I know so well, terrifies me because I can't read the faces. I'm not able to fill in the gaps. And so much of the work of the imagination depends on that tension between what one knows intimately and what one cannot possibly know.

What is your writing process like? Is it regimented or do you write in fits and starts?

It is extremely regimented.

Once I have a book going on -- and there is little in life that is more important to me -- I don't move.

In the two to three years it took to write The Way Things Were, I hardly went anywhere. There was nothing I looked forward to more than that period between 4 am and 10 am, when I would work on my book.

The rest of the day was centred on a concerted attempt at recovery, at making myself good for my book the next day.

And what's nice is that if you remain in that state, the book working away in the back of you mind, the writing is ready when you return to it; it needs only to be copied down.

You have written extensively and incisively about Pakistan in your journalistic career. Has there been any kind of a radical shift in your perception of the country?

I've just seen it get worse and worse.

Photograph: Press Information Bureau

Back in March 2014, you were quoted as saying that a prime minister like (Narendra) Modi could bode well for India. Nearly eight months into his tenure, how do you think he measures up?

I simply feel the reason I said that was for the last five years, we had a prime minister who couldn't do anything about India's foreign policy, he certainly can't do anything bold.

Now we have a prime minister who IS the prime minister. He says what he means.

We've had this approach to dealing with Pakistan that we must be generous, we must be magnanimous, let the Pakistanis do what they desire, we will stand higher.

That's not a good idea.

It is very important to assert that you are capable of using force, WILL use force if necessary and once that's clear to the person you're dealing with, it's a more honest place to begin in. You can actually get somewhere.

What India always thinks is graciousness, Pakistan interprets as weakness.

When I talk about Indo-Pak relations, I'm not talking about some kind of love fest between the two.

What I'm saying is that any country's foreign policy, especially if they're dealing with an enemy country, should primarily be about creating an area of security.

We are sitting in a city that was attacked by Pakistan a few years ago.

And with the knowledge of the Pakistani State, has Modi made India more secure? I think probably he has.