A C Narayanan Nambiar's name will not ring a bell because he operated in the shadows where statecraft and secrecy overlap.

An anti-colonial warrior, he was imprisoned in concentration camps and lived an extraordinary life, intricately linked to momentous turns in history.

Having lived in Europe for five decades, he was witness to and entangled with what we today -- with the benefit of hindsight -- call recent history.

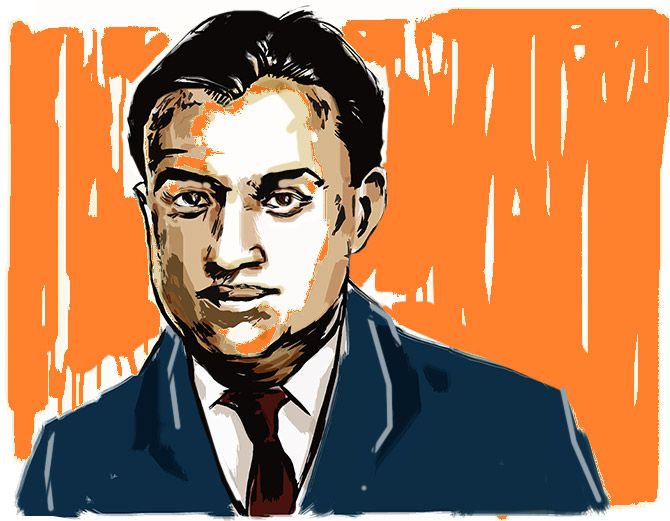

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

There are not many people who will tick the following boxes:

A close aide of Netaji.

A close associate of Jawaharlal Nehru.

Someone who Indira Gandhi relied on and trusted.

But add to the above list a person who was also an Indian journalist in Europe in the tumultuous days preceding and during the Second World War, there is really no one, one can pinpoint.

But then, Arathil Candoth Narayanan Nambiar is not a name that will ring a bell, simply for the fact that for the most part, he operated in the shadows where statecraft and secrecy overlap, and he preferred to live in the shadow, maintain a low profile.

In April 1980, when Vappala Balachandran, a senior intelligence officer who was special secretary, Cabinet Secretariat, was assigned the task of keeping a discreet eye on the health and welfare of Nambiar -- Nanu to friends -- he had no idea that the meeting will form a solid bond that will last beyond the latter's death six years later.

Nambiar's life was extraordinary, to say the least, intricately linked as it was to momentous turns in history, when he was both a player and an observer.

Having lived in Europe for five decades, he was witness to and entangled with what we today -- with the benefit of hindsight -- call recent history.

Yet, even as the two men spent time together, discussing, dissecting the days bygone, and the characters that shaped the world we inhabit today, Balachandran would realise only 15 years later that what he had been told was not the complete picture.

Or that unravelling it would become a mission for him.

"I came across startling details during my long research into his life first by reading published literature and then scouring through declassified secret intelligence records."

A Life in Shadow, The Secret Story of CAN Nambiar, then, is the outcome of the long and hard pursuit by Balachandran to fill in the gaps in Nanu's life. His wonder at what he managed to find out about Nambiar's remarkable life comes through in the book, published recently by Roli Books.

"Mr Nambiar was a treasure trove of information on European history, governance, security and power play of European nations from the 1920s to the 1980s. This helped me in learning more about the turbulent history of that region," Balachandran tells Saisuresh Sivaswamy/Rediff.com in a revealing interview about a lesser known Indian.

What impelled you to tell the story of ACN? I mean, his life was shrouded in secrecy -- as I am sure that of many others who have done yeoman service from the behind the shadows. So why did you feel you had to tell his story in particular?

Although I was in constant contact with him from 1980 till his death in 1986 I did not realise that he was responsible for a major operation organised by Subhas Chandra Bose in pre-Second World War Germany.

This became clear only in 2001 when I read a book written by German writer Rudolf Hartog about the 'Indian Legion' in Nazi Germany raised by Subhas Chandra Bose as his future Indian Army.

Hartog was the interpreter in the Legion. It gave vivid details on how the Legion was run as a disciplined army although all trainees were Indian POWs (Prisoners of War) captured by Germany.

I was rather surprised to know that Mr Nambiar was the main person administering this 4,000-strong army.

That gave a new dimension to Mr Nambiar's life story which I did not know earlier although I was meeting him regularly between 1980 (when I first met him) and 1986 (the year of his death).

During our regular meetings, first at Zurich and later in Delhi, Nambiar did not tell me all these details except that he had worked for Bose.

Hence I decided to investigate further. I came across startling details during my long research into his life first by reading published literature and then scouring through declassified secret intelligence records.

One feels an almost avuncular relationship between the two of you. Would you call him the most unusual figure you have met in your long years in intelligence?

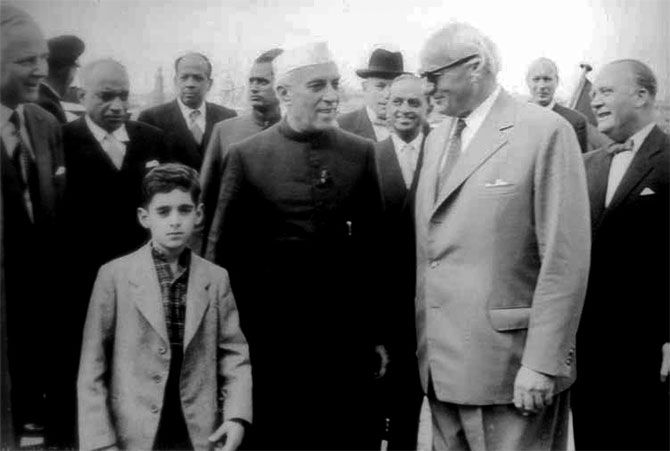

Perhaps yes. He was very kind and considerate to me although he was on a first name level with Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi.

When I first met him in 1980 he was 84, I was 43. Despite this age difference he was very polite and friendly, exhibited no arrogance despite knowing that I was a middle level officer who was assigned this work as part of my duty.

On the other hand he was unfailingly courteous, always enquiring about my comforts. At the same time he was a treasure trove of information on European history, governance, security and power play of European nations from the 1920s to the 1980s.

This helped me in learning more about the turbulent history of that region.

ACN's life was a secret because that's the way he probably wanted it to be. Were he alive, would he have consented to a book on his story, you think?

I am asking this since from your book I am unable to make out if he expressly authorised a book on his life, despite giving you the oral transcripts, etc.

I brought up the subject of suggesting him to write his memoirs only when I saw him in deep depression after Mrs Gandhi's assassination.

I thought that this would lift him up.

Even earlier, he used to be depressed at the very thought of shifting his location from Europe where he had lived since 1919. In fact, he had written to me from Zurich on February 2, 1984: 'There are moments, Balachandran, when I think that it would not be a bad development if I passed away quietly here, thereby not making necessary thoughts relating to the trip now under discussion...' (Page 257).

I had, however, assured him that everything would be taken care of in New Delhi.

But the death of Mrs Indira Gandhi shattered him. He refused to write his memoirs since his health would not permit. I then suggested to him to dictate his memoirs to a tape recorder. His mood improved since he was busy in dictating his memoirs.

However, I am not too sure whether he would have written his memoirs on his own, had this contingency (Indira Gandhi's death) not arisen.

He used to parry that suggestion saying that he was an ordinary man and had done nothing great. But he consented to dictate his memoirs on my request.

I cannot say whether he would have permitted me to write this book had he been alive. But I felt that I owe a duty to posterity to record the story of a less-known freedom fighter after I read Rudolf Hartog's book.

One of the things that stand out in your book that both Nehru and Bose -- who Indians are repeatedly told were antagonistic to each other -- respected ACN immensely.

Two questions arise: One, was the so-called animosity between them, fiction?

Two, what does this tell about ACN?

I have already made this clear in my book. Both were friends.

Bose was the first person to receive the ailing Kamala Nehru on her arrival in Vienna in May 1935. Nehru was in prison.

I have written: 'As Nambiar saw it, Nehru and Bose differed not on the aim of independence but on the modalities. Nehru, although doubting certain assumptions and conclusions of Bose, never doubted his patriotism nor harboured any hatred.'

'Bose on his part recognised Nehru's importance and influence in India's struggle although he felt that Nehru's pro-British attitude could be a problem.' (Pages 261-62).

No doubt Bose felt unhappy that Nehru sided with Gandhiji when he had differences with him.

One of the first acts of Nehru on becoming prime minister was to enquire through Nambiar about Emilie Schenkel (Netaji's wife) and to arrange to send help to her.

Also, Anita Bose (Bose's daughter) stayed with Nehru during her visit to Delhi in 1960 (pages 167-169).

In my 'Notes' (pages 287-88) I refuted the recent allegation that Nehru had 'snooped' on Bose and his family.

Did his close association with Bose make ACN privy to what really happened to Netaji?

Did you two discuss his end? What was ACN's view on the last days of Bose?

Mr Nambiar did not know the full details regarding Netaji's death as he was under Allied troops' custody.

His last letter dated January 12, 1945, to Bose sent through German submarine U Boat 234 did not reach him as the boat surrendered to the American navy on May 14, 1945.

Mr Nambiar, who was on the run after the Allied bombing, was arrested on June 7, 1945.

Bose is reported to have died on August 18, 1945. Mr Nambiar did not have any contacts with Bose's colleagues in the Far East after the very traumatic war period when he was rendered stateless.

The British government did not want him to stay in Europe. Nor did they want him to go to India where he would have become a hero. It was at this juncture Nehru saved him and asked him to come back to India.

The question that remains on one's mind while reading your book: Was ACN a foreign spy? How much of certainty does your answer have?

He was never a spy for the British, German or Soviets.

The voluminous declassified British Intelligence records that I purchased from a library in Leiden (Holland) in 2005 for the period 1912-1950 prove this.

Had he been a spy there would have been references about his actual activities as a spy like clandestine meetings, passing on secrets etc.

The allegation that he was a 'suspected Soviet spy' arose when a particular London-based Indian journalist saw the caption of a bunch of declassified British intelligence records in October 2014, which among others described the contents of this group as 'Soviet intelligence agents & suspected agents.'

Anyone who knows the bureaucratic practice of keeping intelligence files would have realised that such generic file captions are given to all the suspects and routinely continued even if there is no evidence.

Also, British intelligence kept all those having 'Leftist' sympathies as 'Communist agents.' Unless one reads the contents of all files one will not know whether really a person was an agent.

I have studied all these files, especially the long interrogation report of Mr Nambiar by Major Bains after his capture.

There is no shred of evidence that he was a 'spy.'

The description of Nambiar in British files swings from him being a suspected 'Soviet agent' to a 'Nazi collaborator.' That is ridiculous, to say the least.

ACN's end: unsung, lonely, and virtually abandoned. Is that how it always ends for those living in the shadows?

Did he make peace with it in his last days?

I would not call that he was 'unsung, lonely and abandoned.'

On the other hand he preferred that type of low profile life. That was why he resigned from hectic diplomatic life twice.

Nehru wanted him to take an active part in his government, but he preferred to be a journalist. He joined the diplomatic service in 1948, but resigned in 1952.

He was again appointed as ambassador in 1952 but resigned in 1958.

When I met him in 1980 he was quite happy to be left alone. He had a small circle of dependable young friends.

It was only on Mrs Indira Gandhi's insistence and his own fears of his old age that made him shift to India in 1984.

He continued to tell me that he had not done anything to be famous.

What explains ACN's reluctance to return to India after the War/Freedom?

Did he fear being hounded here by political foes, or was there more to it?

He had no political foes. His reluctance to come back to India was because of his mental depression in the wake of long imprisonment in Allied forces' concentration camps and equally long internment.

He had cut himself off from his family and was not too sure what awaited him in India if he returned.

He preferred to be in Europe even in penury. That was until Nehru personally took initiative in sending emissaries to meet him, calming him down by making him stay with him and assuring him of his support.

Incidentally, he did not very much like the diplomatic job offered to him in Berne. but agreed to accept it since it was offered by Nehru.

One of the questions on everyone's minds is the surveillance on Bose's family for many years post Independence.

What exactly did Free India, that is, the Establishment, worry about?

Why had Bose become a bogeyman?

I have answered this question in my notes (Note No: 52).

The watch on Bose started in 1922 when the British government noticed Comintern sending Abani Mukherjee to Kolkata to influence Chittaranjan Das and Subhas Bose.

Abani Mukherjee spent 11 months in Calcutta. Later, Bose's close contacts with the Communist party were mainly through Soli Batliwala who was the link between the Communist Party of India and Subhas Chandra Bose.

This channel was used by Bose in 1939 to forward his proposals to the Soviet Union.

For the British government any link with Comintern was treason. Nehru did not start any surveillance on Bose or his family.

The question is: Why did independent India continue the watch?

The answer to this is given by British historian Christopher Andrew who was given full access to British intelligence records to write the 'authorised history' of MI-5.

One of the unwritten agreements during the transfer of power to India in 1947 was the secret positioning of a 'security liaison officer' (SLO) at New Delhi as MI-5's representative.

He was almost 'embedded' in the Intelligence Bureau.

As a result IB closely followed Britain's intelligence priorities even though an independent democratic country was born.

Andrew quotes instances: T G Sanjeevi Pillai, IB's first director, did not like V K Krishna Menon although he was a close confidant of Prime Minister Nehru.

Declassified British archives speak of a loud disconnect between the Nehru government's strategic policies and the priorities pursued by the IB.

Apart from the Krishna Menon episode, the disconnect was evident during the exchange visits of Soviet leaders Bulganin and Khrushchev to India and Nehru's visit to the USSR which heralded closer Indo-Soviet relations in 1955.

One year later there was a chill in Indo-UK relations when Nehru condemned the Anglo-French invasion on the Suez Canal.

Andrew says that this 'had little impact' on the IB-MI-5 collaboration.

IB even allowed an MI-5 officer to study their records on Moscow's subsidies to Indian Communists.

There is no record that Nehru was even aware of this relationship since he did not directly supervise the home ministry under which IB worked.

My assessment is that IB mechanically continued this practice of watching Indian Communists, their families and those who were communicating with them.

In your Afterword you refer to George Fernandes' remark about ACN, which was possibly born out of the puzzling reliance, Indira Gandhi -- who suffered very few men -- placed on the latter.

Was Fernandes hinting at a dark secret regarding ACN's ties to Bose and the Nehrus?

(On June 19, 1988, the Indian Express reported, Fernandes told the newspaper that unravelling of the activities of Mr Nambiar was the 'biggest story of the century'. 'The full account of the Nehru family, living and dead, will be known when we are able to get a complete dossier on Narayan Nambiar's activities abroad,' he said).

I have no idea why George Fernandes made this remark without knowing anything about Nambiar. It must have been blind hatred towards Nehru and Indira Gandhi, which unfortunately exists even now.

Nehru did appoint Nanu as envoy. But overall, did India benefit from the wealth of ACN's collective wisdom and relationships across the international spectrum?

Nehru valued Nambiar's contribution as his letter dated May 8, 1958, on his retirement would reveal (page 210).

Even after his retirement Nambiar used to send valuable suggestions to him and to Mrs Gandhi on the running of our foreign ministry. Both Nehru and Indira Gandhi acknowledged these letters and took action.

Even the German government had excellent comments to make on Nambiar's contribution towards Indo-German relations as Jan Kuhlmann had written in his book Subhas Chandra Bose und die Indienpolitik der Achsenmachte: 'Even before he was named ambassador to Germany, Nambiar had nurtured contacts with his friends there. With German ex-officers of the Indian Legion he founded an Indo-German Society in 1950.'