'The focus on countering terrorism brings to the issue Beijing's non-serious approach in this regard. India's permanent representative at the UN has raised in vain the issue of funding and the release of 26/11 suspect Zaki-ur Rehman Lakhvi. But China has blocked these objections since December 2014 at the UN even after 'highest levels' in India intervened,' notes Srikanth Kondapalli, reviewing the India-China military exercises in Kunming.

Quietly, as India began the trilateral exercise with the most modern naval forces of the United States and Japan in the Bay of Bengal on October 12 (to last till October 19), not far away it also began the fifth version of the 'hand-in-hand' joint operation with China's People's Liberation Army in the southwestern Chinese city of Kunming on the same day, but for 12 days.

Of course, the maritime exercise with the US and Japan is significant and strategic in nature given the fortunes of every country determined on the high seas. Moreover, this is a joint exercise with tactical principles and operations shared between the US, Japan and Indian forces with high technology gadgets.

On the other hand, the Kunming event is mentioned in the official discourse as a 'joint drill' or a 'joint operation' with focus on counter-terrorism, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

Also, unlike the full-fledged Malabar exercise, 'observer' military delegations are currently participating in Kunming.

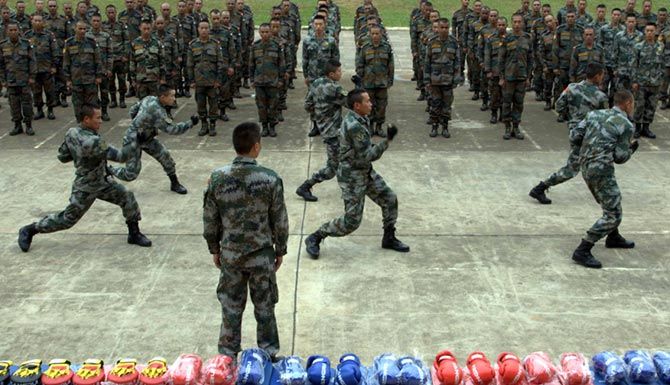

The command levels in the 'hand-in-hand' operations also suggest that these are symbolic and ceremonial in nature. The 144 Chinese infantry troops -- about a Company-level military formation -- are led by a Lieutenant General level officer Zhou Xiaozhou. The 175 Indian soldiers are led by Lieutenant General Surinder Singh.

General Zhou mentioned the scope of these drills thus: 'To expand the scope of military interaction, facilitate exchange of best practices in counter-terrorism operations, enhance mutual understanding and trust and further promote friendly relationship between both militaries.'

The level of participation, command level and objectives suggest that 'hand-in-hand' are mainly meant to address political mistrust levels and usher in a step-by-step improvement in contacts between the two armies.

This is essential against the background of the devastating border clashes both fought in 1962 and to the subsequent Cold War freeze in relations, including in the military field. The latter sometimes poses concerns, such as the April 15 to May 6, 2013 Depsang Plains incident when Chinese troops marched 19 km inside the Indian-claimed area in the Western Sector of the border.

Such major transgressions were repeated at Chumar in September 2014 during President Xi Jinping's visit to India and recently on September 12 in the Daulat Beg Oldi area.

In order to overcome these hiccups, both nations initiated annual dialogues between the military establishments in addition to the 'hand-in-hand' operations. The previous such events were held in Kunming in 2007, Belgaum in 2008, Chengdu in 2013 and in November 2014 at Pune.

After China refused a visa to Lieutenant General B S Jaswal -- the Indian Army's Northern Command commander who headed the Indian military forces in Jammu and Kashmir -- in 2010, India in protest postponed all such military engagements till these were resumed in 2013, suggesting that such military events are subject to the political weather.

The main theme of these activities is counter-terrorism, designated by both countries as the number one security challenge to their respective nations. India mentioned 'cross border terrorism,' while China code-named these as 'three evils' (against separatism, extremism and splittism). 'Splittism' here meant efforts to counter the Tibetan movement.

While India had endorsed officially the 'three evils' discourse, China contented itself in joint statements with India in 'opposing all forms of terrorism' -- thus generalising the issue.

The focus on countering terrorism brings to the issue Beijing's non-serious approach in this regard, much to New Delhi's chagrin. India's permanent representative at the UN raised in vain the issue of funding and the release of 26/11 suspect Zaki-ur Rehman Lakhvi. China has blocked these objections since December 2014 at the UN even after 'highest levels' in India intervened.

Earlier as well, when India invoked UN Resolution 1267 to block funding for the Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Tayiba terror groups, China's 'technical' responses basically stalled strictures on these groups in Pakistan.

Apart from the political divergence, the 'hand-in-hand' operations in Kunming, Belgaum, Chengdu and Pune also brought forth differences in the military approach to tackle the issue. For instance, the Chinese approach -- much exemplified by its actions on Uighur groups in restive Xinjiang -- is to follow a 'scorched earth' policy of bombing all suspected hideouts indicating the huge collateral damage to society, people and property. This has only aggravated the situation in China today.

Since 1996, both militaries have introduced confidence building measures in the conventional field including border personnel meetings, 'hot lines' at tactical levels, no major exercises, no fly zones, etc. Over a period of time these have deflected active conflict between the two armies and ushered in 'peace and tranquility,' although border transgressions now and then increase tensions. However, these have not reduced the mutual mistrust which still prevails both at the political and military levels.

For these reasons, while the Malabar exercises are strategic in nature, the 'hand-in-hand' operations remain tactical. India and China need to more to usher in a 'strategic and cooperative partnership signed in 2005.

Dr Srikanth Kondapalli is Professor in Chinese Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University.