China is where the action is, and from where new ideas ('String of Pearls', 'One Belt, One Road') emanate.

The Belt-and-Road initiative alone is unmatched in its sweeping dimensions, says B S Raghavan, the distinguished civil servant.

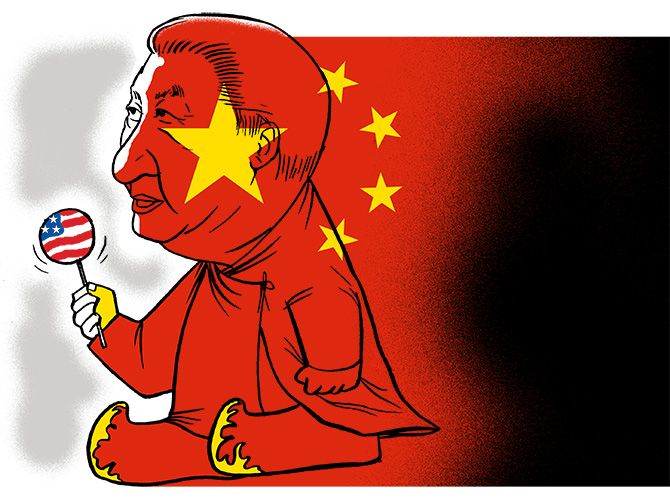

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

It didn't require a Nostradamus to predict the happenings at Hamburg, Germany, during the meeting of the G-20, held on July 7-8.

It was expected that hordes of protesters from far and near would descend in their thousands, as they had been routinely doing wherever and whenever world leaders met from the Battle in Seattle in 1999, protesting the apathy of rich countries towards inequalities of globalisation, jobless growth, trade policies, ravages on environment and the like.

A measure of equality among countries has been achieved, at least in respect of the degree of violence that accompanies such protests in terms of attacks on the police, destruction of public property, looting, arson and so on, and Hamburg was no exception.

A novel feature this time was the blasting by the protesters of music from Jimi Hendrix, included in The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as 'arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music', in a bid to drown out the classical music playing at the concert hall where the world leaders were meeting.

As if the 15-page Declaration issued at the end of the summit was not pontificatory and platitudinous enough, 14 'agreed documents' were added to it, making it respectably voluminous and forbiddingly unreadable.

It made the hitherto unthought of revolutionary revelation that 'we can achieve more together than by acting alone', and went on to repeat the same nostrums as contained in many such previous declarations to 'address major global economic challenges and to contribute to prosperity and well-being' so as to bring about 'strong, sustainable, balanced and inclusive growth'.

Once again, the leaders pledged themselves rather pretentiously to 'shaping an interconnected world' and to finding solutions for such things as 'terrorism, displacement, poverty, hunger and health threats, job creation, climate change, energy security and inequality, including gender inequality, as a basis for sustainable development and stability'.

The leaders made obvious their determination to 'decide today' to take 'concrete actions to advance the three aims of building resilience, improving sustainability and assuming responsibility'.

The world will watch in great suspense and with bated breath how they are going to realise these three woolly-headed aims.

That the presence of the brisk, brusque, no-nonsense, tit-for-tat tweeting US President Donald Trump would cast a dark shadow on the conclave must also have been a foregone conclusion.

For the first time, the G-20 was forced to depart from the tradition of unanimity by having to take note of the US decision to dump the Paris Agreement on measures to ward off climate change.

It, however, consoled itself by stating that the 'Paris Agreement is irreversible'.

In line with Trump's campaign call for 'America First' and the implied concomitants of protectionism, the group's past insistence on the duty of countries to work for free trade had also to be diluted by conceding their right to protect domestic industry.

In short, the maverick US president managed to bring the G-20 down by a notch to G-19.

A commentary published in The Guardian postulates that, on present showing, it will soon be a 'G-Zero' world, that is, one in which no country or bloc can shape or direct global events.

My prediction is different.

I reckon that geo-politics and what Arnold Toynbee called the cyclical pattern of history will set the world order unrecognisably apart from the existing one.

Drawing his analogy from biology, Toynbee argued that the life cycle of each civilisation inevitably runs a course in which it passes from youth to senility and final decay.

In his Study Of History, based on an analysis of the rise and fall of 23 civilisations, he concluded that no single country or civilisation held sway for ever, and it faded away when its kit of recipes to overcome existing and emerging moral, social and economic challenges got obsolete or exhausted.

Although Toynbee was celebrated for his theory, the theory itself was rooted in common sense.

Alfred Tennyson, Britain's poet laureate, had famously said in his epic poem Morte d' Arthur, in the mid-19th century itself, that 'the old order changeth, yielding place to new/Lest one good custom should corrupt the world'.

Literatures of many languages are replete with proverbs and adages to the same effect.

From the dawn of history, civilisations and empires that seemed permanent and all-powerful have disappeared one by one replaced by new ones.

This was as true on the world scale, as it was within a landmass such as India.

The European races -- especially the British, French, Spanish, Portuguese -- seemed invincible at one time, but were soon supplanted by the Americans, leading to the pithy pronouncement by George Canning in 1826 about the New World coming into existence 'to redress the balance of the Old'.

The 20th Century was wholly the American Century.

Now, the hundred years of the US domination of the course of events, economies, cultural norms and thought processes of the world is obviously on the downslide.

The Western industrial nations seem incapable of resurgence.

The effect of the influence the US and the West once enjoyed in terms of technology and power plays will no doubt linger for a lot more time, but their present enervated state is affecting their capacity to prevail.

All signs point to the advent of a new world order centring round China.

That's where the action is, and from where new ideas ('String of Pearls', 'One Belt, One Road') emanate.

The Belt-and-Road initiative alone is unmatched in its sweeping dimensions. It involves reconciling the divergent interests of so many countries, economies, political systems and cultures and bristles with intractable operational problems and mind-bogging financial outlays.

But China has staked all its prestige and reputation on it, and has all the manpower and technical resources, economic might and political clout to pull off this seemingly impossible feat.

Just reinventing the ideas of Marx and Engels and blending them with the precepts and prescriptions of Confucius and Sun Tzu and, at the same time, beating the West and the US in their own game, is no mean achievement on China's part.

The present century could have been an Asian century if India had made good.

It started its journey as an independent nation along with China, but lags behind it in many respects.

China is way ahead in R&D, creativity, innovation and ingenuity.

The world, therefore, to all appearances, is heading for G-1.

The only question is whether it would be able to avoid the Thucydides Trap, according to which the most dangerous period in international history is when a rising power challenges the pre-existing status of established powers.

For, it has been found that in 11 of 15 cases over the last 500 years, when an emerging great power challenged established great powers, the result was conflagration of unimagined proportions.

B S Raghavan is a former member of the Indian Administrative Service, and currently Patron of the Chennai Centre for China Studies.

He plays an active role in the Indo-Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry and is a frequent commentator on national and international affairs.

He was a member of the Joint Intelligence Committee at the time of China's invasion of India.>

The views expressed are personal.