'The flashpoint for the deeper battle over the soul of this country has come over Aadhaar. And that is because internal to Aadhaar itself, within the very design and usefulness of the project, lies the division between the clashing images of India,' says Mihir S Sharma.

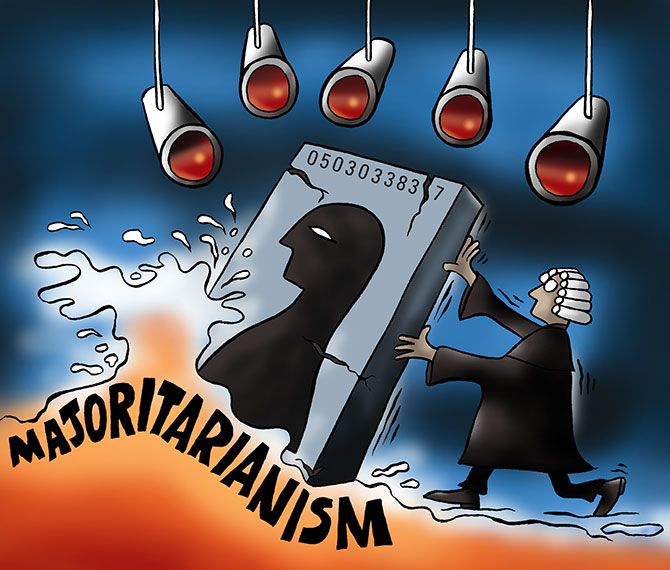

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com.

The judgment affirming that Indians do, in fact, have a fundamental right to privacy is momentous. It is among the most important constitutional decisions in decades; some have compared it even to Kesavananda Bharati in 1973, which decisively limited Parliament’s ability to amend the Constitution.

The reason why it may be so important is that it is a reminder, one which was sorely needed, that India was conceived of as a nation that prioritised the individual over the collective.

It was a country where majoritarian sentiment — whether legislative or popular — would always have to respect the rights of the individual, and the choices that individuals wished to make.

This country has, for some years now, been slipping into a very different conception of itself. I do not need to spell out the lineaments of that self-image.

Certainly, dissent is not popular; distrust and caution about the State are discouraged; and the very notion of permanent and empowered minorities, whether of descent, belief or ideology, is considered troubling.

Respect for minority rights is, if the minority is religious, ‘appeasement’; if the minority is political, ‘indecision’; and so on.

This judgment by the Supreme Court tries admirably to address this slide. The degree to which it succeeds determines the degree to which the Court, and the Constitution that we gave ourselves nearly seven decades ago, has the power to restrain a turbulent majoritarianism at this very dangerous point in our history.

You would think that given this clash of perspectives about who we are and over what may underlie our Constitution was inevitable, it could have emerged through any policy disagreement.

I disagree, however. In some ways, it is no coincidence that the flashpoint for this deeper battle over the soul of this country has come over the Unique ID project, or Aadhaar. And that is because internal to Aadhaar itself, within the very design and usefulness of the project, lies this division between the clashing images of India.

Remember how Aadhaar was sold to us, back in the early days of the second United Progressive Alliance government? Think just of the words being used then: choice; voluntary; empowerment.

Now think of the words you associate with Aadhaar right now: mandatory; savings; database. It should be clear that the project has, in and of itself, two different faces, corresponding to these two ideas; and over time it has swung from one to the other.

The reason why Aadhaar was such an important development, why I and others welcomed it at the time -- and why it is still so important -- is that it has and had the potential to turn the petition seeker from the government into a full citizen with entitlements.

Rather than being someone who had to grovel to demonstrate identity and receive the services due to her, an Aadhaar recipient could -- together with justiciable right to services laws -- be able to demand them.

To those who cared about strengthening the individual’s rights in India, this seemed paramount.

I also felt that Aadhaar, making the individual the eventual destination of welfare, allowing for the possibility of proper targeting of future welfare, would allow for the slow dissolution of the other networks that had been set up because of the imperfection of our welfare states.

Again, it would strengthen the individual with respect to the other groups.

It would be foolhardy today to suppose that Aadhaar, as it is currently being implemented, will still strengthen the individual. In fact, it has turned into a bureaucrats’ plaything. Rather than reducing barriers, it is increasing them. Rather than being seen as ensuring that Indians find it easier to access services, it is being seen as a way of ensuring that the State knows who is accessing its services.

It is being driven by the justifications of savings and exclusion, and not by inclusion. It should be clear how much the project has altered.

Many bear blame for this. The UPA government that pushed Aadhaar failed to put the robust systems into place that so many people warned them would be necessary if it was to not become just another, if far more powerful, tool for the State.

It was too slow, too divided, and too willing to compromise — there should never have been a demand, for example, for an address proof or some other form of identity at the time of registration.

Nandan Nilekani, who sold and implemented the project so well, has sadly failed to serve as a voice of caution when we needed him the most, over the past two years. And the less said about the current government, which has overused and thus debased Aadhaar, the better.

Even the Supreme Court has failed to ensure the implementation of its 2015 order reminding the government that Aadhaar was meant to be voluntary and not mandatory. Hopefully this judgment will be the beginning of a much needed course correction.