Sardar Udham sets a great standard which, Utkarsh Mishra believes, would be emulated by other film-makers who want to make movies of this genre.

Forgive me for living under the rock, but I didn't know Sardar Udham was a Shoojit Sircar movie until the credits rolled in. Therefore, I was quite apprehensive about watching it, thinking that I knew how it would turn out.

After all, aren't we living in a time where we're told by Union ministers that it was Mahatma Gandhi who 'advised' V D Savarkar to file mercy petitions when the latter was serving two life sentences at the cellular jail in the Andamans?

Books and articles are being written by 'nationalist historians' who repent that 'true Indian history was not given its due under Congress rule' and it needs to be 'rewritten'.

So when I came to know that a movie has been made on Shaheed Udham Singh -- the great martyr who assassinated Michael O'Dwyer, the former lieutenant governor of Punjab who had a major role behind the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919 and the atrocities inflicted on Punjab during those months -- I suspected it to be an exercise in a similar direction of 'rewriting history' that would try to paint a different picture of Udham Singh suitable to the prevailing narrative.

But after watching it, I realised how unfounded my prejudices were.

This is one of the finest historical films ever made in India.

The movie is devoid of all jingoism, melodrama and over-enthusiasm which are usually part and parcel of patriotic movies made in India.

Its meticulously researched script, remarkable attention to details, a profound execution and engrossing performances make it a must watch.

The movie works because it sticks to facts as far as it could. And even where it doesn't, it doesn't seem completely unreal.

One may have issues with the screenplay, which is not only non-linear but may seem disorganised or even chaotic, but it is certainly not whimsical.

The climax is undoubtedly long-drawn and may intrigue someone into asking why the Jallianwala episode, the motivation behind Udham Singh's act, is shown after his trial and sentencing. I have my understanding about why it needed to be so and I will come to it later.

The life story of Udham Singh

This is not the first movie on Udham Singh.

In 1999, the birth centenary year of Udham Singh, a movie named Shaheed Udham Singh, starring Raj Babbar in the titular role, was released. I have seen only glimpses of it once on TV and sometime ago on YouTube. It may not be outright bad, but, as much as I saw, it is laden with over-dramatic performances.

Moreover, it is not like Udham Singh's role in the Indian National Movement has been completely ignored. Some of his letters from prison in London were published in 1974.

Months before Udham Singh's birth centenary in 1999, two of his biographies were published -- The Trial of Udham Singh by Sikander Singh and Challenge to Imperial Hegemony: The Life Story of a Great Indian Patriot Udham Singh by Navtej Singh.

Reviewing these two books in a 2001 article, Professor Chaman Lal of Jawaharlal Nehru University -- whose work in publishing Bhagat Singh's documents and narrating the history of revolutionary movement for Indian Independence is phenomenal -- wrote that 'In spite of weaknesses, Navtej Singh has tried to present Udham Singh in an historical setting as a national revolutionary, whereas Sikander Singh has just written a sentimental book'.

He rightly says that it is much easier to write about Udham Singh's life in England, since that is on record.

What is more difficult is 'constructing his life story from his birth to his going to England'.

Chaman Lal writes that both these books 'have presented a fictional reconstruction of Udham Singh's early life' and that 'Raj Babbar and his team has understandably used Sikander Singh's book to make a film in true Hindi filmi style'.

In 2019, the centenary year of Jallianwala Bagh, British journalist and author Anita Anand released her biography of Udham Singh, titled The Patient Assassin, A True Tale of Massacre, Revenge and the Raj.

She writes about Udham Singh's early life in detail.

Her account of this period is mostly based on Sikander Singh's book, Udham Singh's statements to police in Amritsar and in London after the assassination of O'Dwyer.

As per Anand, Udham Singh and his brother were raised at an orphanage in Amritsar after losing their parents in childhood.

After leaving the orphanage, Udham enlisted to serve in the Great War and was posted in Basra but was 'declared unfit for service' within six months and was sent back to India.

He re-enlisted barely a month later and was again sent to Basra and Baghdad, but this time as a pioneer, given his carpentry skills he learnt while at the orphanage.

He came back to India in early 1919 after the war was over and worked at several places but subsistence was difficult.

He found a job at the British-owned Ugandan Railway Company and went to East Africa where he came in contact with the with the Ghadarites and his revolutionary career began.

He left the job, obtained a passport in the name of Sher Singh and came to India.

Sardar Udham, on the other hand, shows young Udham as a factory worker who is content with his life, has a love interest and simply wants to live a happy life.

It makes no mention of his struggles to earn a living or going to several places before finally joining the revolutionary ranks.

This, I believe, is done to contrast his two lives before and after the Jallianwala Bagh. And there is hardly an issue to picked at this cinematic liberty. As with some others which are clearly fictional sequences but were necessary to tell the story effectively.

The standard of the film rises substantially as it shifts to the London of 1930s. You don't see such painstakingly accurate cinematography in Indian movies.

While Udham's character makes desperate efforts to seek his target, radio broadcasts in the background inform the viewer that London is now at war with Berlin.

It's a clever placement of the fact that Udham's task was rendered more difficult as World War II had reached the heart of Britain.

Moreover, it was the war because of which Udham's action got substantial coverage in Berlin and other countries at war with the Allies, with Joseph Goebbels using his story for Nazi propaganda.

On the other hand, a lesson they learnt during Bhagat Singh's trial a decade earlier made the British very scrupulous about the coverage of Udham's trial.

Orders were issued to the press not to publish his speeches and statements.

It was only in 1996 that his speech at the trial court and other documents were published after years of efforts by the Shaheed Udham Singh Trust.

The movie captures all these details accurately.

Vicky Kaushal's delivery during the court scenes is remarkably different from his conduct during interrogation by Scotland Yard, where he mostly sits stone faced.

However, trial records state that Udham was 'keen to confess what he had done and was anxious that the blame should not fall on someone else'.

His prison letters published in 1974 show that he even wrote to friends in a way that a stranger would write to someone so as not to direct police's suspicion towards them.

The movie accurately shows Udham meeting with Indian as well as British Communists in London, and discussing with them how to plan further action, as their organisation in India was practically annihilated after the Lahore Conspiracy Case and the execution of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru in 1931.

As the movie shows, Udham did not mince any words in his speech before the judge and the latter did interrupt him several times, asking him to stop, when he used phrases like 'dirty dogs' and 'mad beasts' for the British.

The sequences where he meets O'Dwyer a few times in London before assassinating him are also not completely fictional.

By Udham's own admission during the trial, he had met O'Dwyer outside Kensington Gardens in London.

The movie has prudently used this fact to push several conversations between them, where Udham questions O'Dwyer about his actions in Amritsar and always finds him justifying those in no uncertain terms.

It is a laudable attempt to picture the revolutionaries not simply as mindless assassins but as someone who gave it a lot of thought even before killing the man who most glaringly represented the barbarity of British rule in India.

As shown in the movie, Udham was concerned that his action must be seen as a protest against the Raj, not just as an assassination.

He did not kill any random British person to avenge Jallianwala, he waited for two decades to get the man responsible for it. A man who represented the naked monstrosity of the British empire and who showed no signs of repentance.

In all these aspects, the movie is very well-researched.

Full marks to its script; and to Kaushal's portrayal of the nuances of Udham Singh's life.

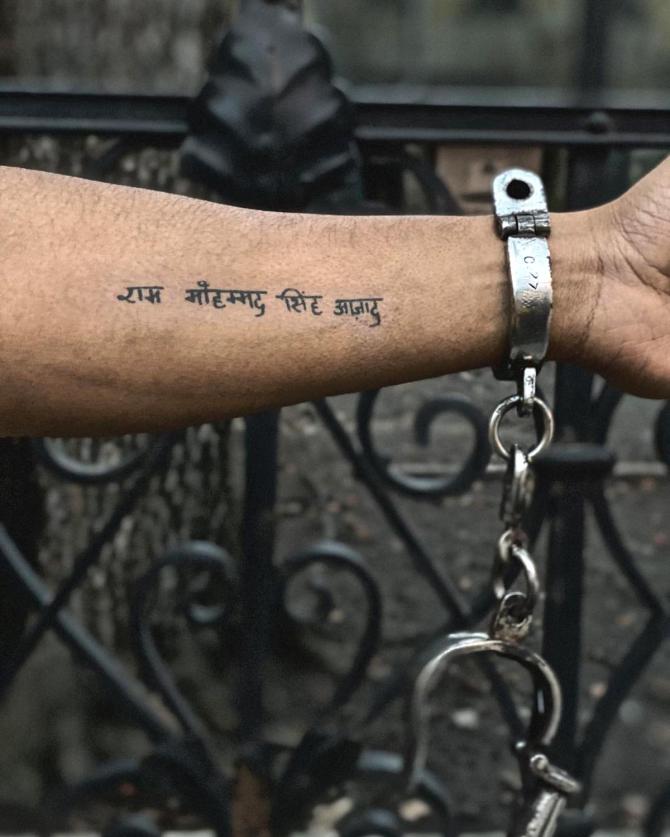

However, one thing that is inaccurate, and I won't blame the movie for it as the books I mentioned also do the same, is that Udham used the alias 'Ram Mohammed Singh Azad'.

In reality, he wrote his name only as 'Mohammed Singh Azad' in letters and documents.

Newspaper reports immediately after his action also refer to him only as 'Mohammed Singh Azad' and so did American journalist and historian William L Shirer in his Berlin Diary.

The portrayal of Bhagat Singh

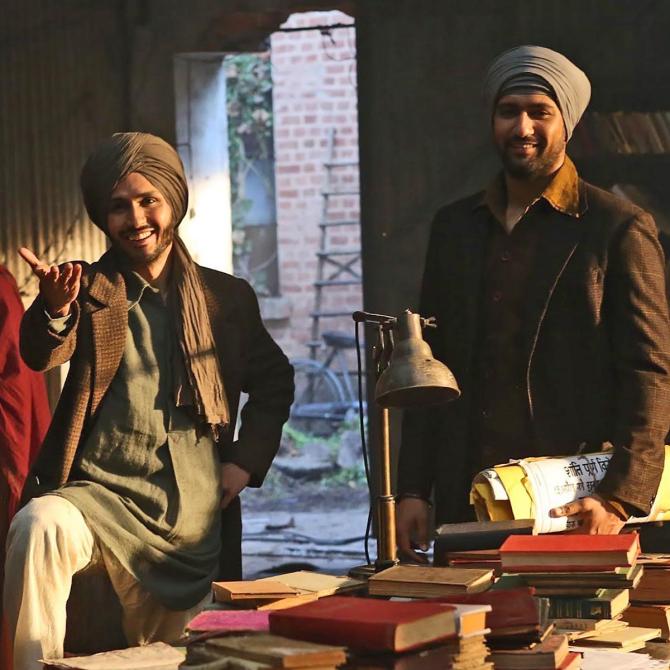

The sequences showing Bhagat Singh come as breezes of fresh air in this otherwise grim tale.

I really liked how Bhagat Singh is portrayed in the movie, which, as per the writings and accounts of his friends published in the aftermath of Independence, comes closer to how he really was, as against what we've seen so far on the big screen.

In our films and theatre, Bhagat Singh's portrayal only as a brave patriot and martyr, which he undoubtedly was, obscures his revolutionary philosophy as well as his youthful gaiety.

He not only liked to read revolutionary and philosophical literature but was also fond of films and often discussed new films and performances of actors with his friends. This is recounted by his comrade Shiv Verma, who has written extensively about him and other revolutionaries, in his memoirs.

So, the movie rightly shows Bhagat Singh telling a comrade, after being asked what will he do first after India attains Independence, 'Me? I will watch a nice Chaplin film.'

Udham Singh had immense respect for Bhagat Singh as did most of Indian revolutionaries even before he was sentenced to death. Because Bhagat Singh was the first to give intellectual and philosophical foundation to India's revolutionary movement.

His understanding about 'What after Independence' was very clear just like his ideas on how to achieve it.

The movie aptly pictures Udham as referring to Bhagat Singh as his 'best friend' and expressing a desire to 'meet him' after being executed. He did carry a miniature portrait of Bhagat Singh with him and also referred to him as his 'guru'.

One particular scene shows the depth of research that the scriptwriters have done and length to which the movie goes to capture important details.

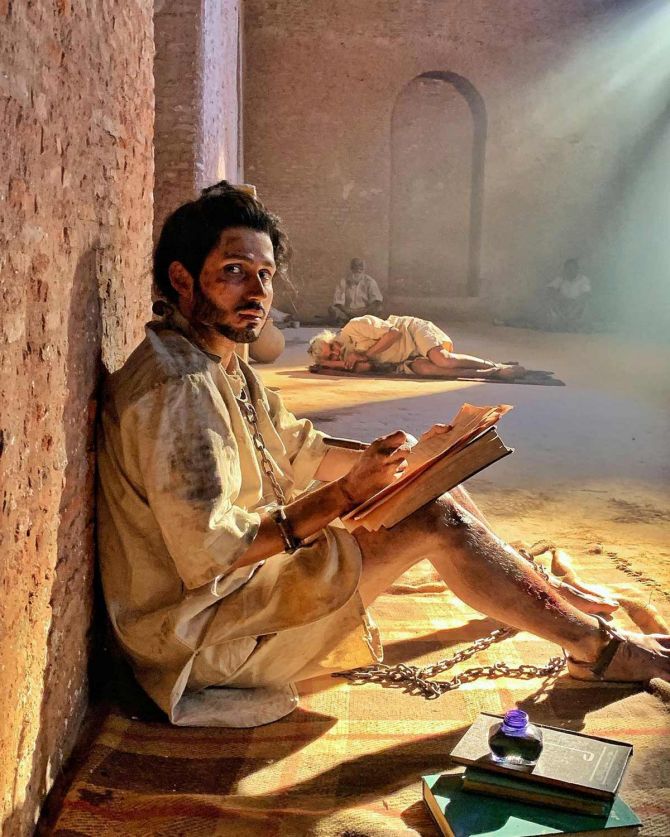

Apparently in hiding, Bhagat and Udham are both reading. The latter is reading Heer by Waris Shah and the former is reading Victor Hugo's Les Misérables.

Hugo was one of Bhagat Singh's favourite writers.

In fact, Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev once had a huge debate over a character in Hugo's last novel Ninety-Three.

On the other hand, Udham really liked the story of Heer-Ranjha and, as shown in the movie, he had actually asked for a copy of the book to take oath on.

The Jallianwala Bagh sequence

Now we come to the climax of the film.

It is hard to describe the enormity of the impact of Jallianwala Bagh on the lives of Udham Singh and his countrymen.

No one could articulate it better than Rabindranath Tagore what the incident meant for Indians at that time, and does even now.

In his letter to the king emperor, renouncing his knighthood, Tagore wrote, 'The enormity of the measures taken by the Government in the Punjab for quelling some local disturbances has, with a rude shock, revealed to our minds the helplessness of our position as British subjects in India.

'The accounts of the insults and sufferings by our brothers in Punjab have trickled through the gagged silence, reaching every corner of India, and the universal agony of indignation roused in the hearts of our people has been ignored by our rulers -- possibly congratulating themselves for what they imagine as salutary lessons.'

Not only O'Dwyer and General Reginald Dyer, 'the butcher of Amritsar', justified their actions in most shameless terms, most of the British officers and even civilians did not find any fault with them.

In fact, a corpus of £15,000 was raised for General Dyer and his family after he was decommissioned and letters of gratitude poured in for him.

Therefore, even the dissenting voices of the Hunter Commission, calling Dyer's actions 'un-British' got it wrong.

It was very British and nakedly blatant.

A 'lesson' that was 'taught to the Indians' by Dyer was that you will meet the most ignominious death even when you protest peacefully. Your lives and rights are solely at our discretion and we can take them away with impunity whenever we want.

It is, therefore, necessary that this story is told in all its grotesque details. And perhaps that's why the director saved it for the last, showing in great depth the impact it had on Udham’s life.

All through the movie, you get a sense of anger, pain and agony that Udham is suffering, which lead to his ultimate action. But it is the climax that shows why they were so intense.

I don't think that the tragedy of Jallianwala was ever captured in such a detailed manner by a motion picture.

Jallianwala is mostly known for Dyer firing at a peaceful, unarmed crowd and killing and injuring most of them.

But what happened in its aftermath, on the night of the incident?

One only needs to read the Punjab Inquiry report released by the Indian National Congress a year after the massacre.

Witnesses recount the fateful night, when the injured, including children, lay bleeding in the garden but were not allowed to be rescued due to curfew imposed by Dyer in the district.

People were desperately looking for their loved ones in the pile of corpses and even when they found them, they could not take them out for final rites.

It was as if the night would never end.

And that's how it is shown in the movie.

I think that the director's call to show it in this way was appropriate even if it made the movie a bit longer.

There are many theories whether or not Udham Singh was present in Jallianwala Bagh on that night.

Some say he was there; some say he was not in India at that time.

But it cannot be denied that the incident completely changed his life and, according to his friends, he often spoke of it in 'anger and agony'.

The movie's climax comprehensively captures this transformation by showing Udham Singh's character exhausting himself to the point of collapse while helping the wounded and lifting the corpses. A part of him dies with each corpse he lifts and each mortally wounded person he sees succumbing.

All this anger is manifested in the final speech of Udham Singh that he delivered in the trial court, where he said, 'I did it because I had a grudge against him (O'Dwyer). He deserved it. He was the real culprit. He wanted to crush the spirit of my people, so I have crushed him... I am not scared of death. I am dying for my country. I have seen my people starving in India under the British rule. I have protested against this, it was my duty.'<

So even if the climax is completely fictional, it is not without its worth in the whole story.

Sardar Udham is a film very different from the ones that Indian audience is accustomed to watch.

If you expect it to possess any of the usual traits that patriotic or historical movies or biopics generally do then prepare to be disappointed.

The movie sets a great standard which, I believe, would be emulated by other film-makers who want to make movies of this genre.