'It is this difference in their personalities -- one in eloquent command of the requirements of Parliamentary debate, the other unable to infuse spontaneity in his script -- that will be as much a factor in who India votes for next year, as other more germane factors,' says Vikram Johri.

Rahul Gandhi's speech in Parliament during the no-confidence motion against the government was nearly equally hailed and dissed. His effort to reach out to the Treasury benches by bringing up the colourful terms that he is labelled with on social media seemed genuine and heartfelt.

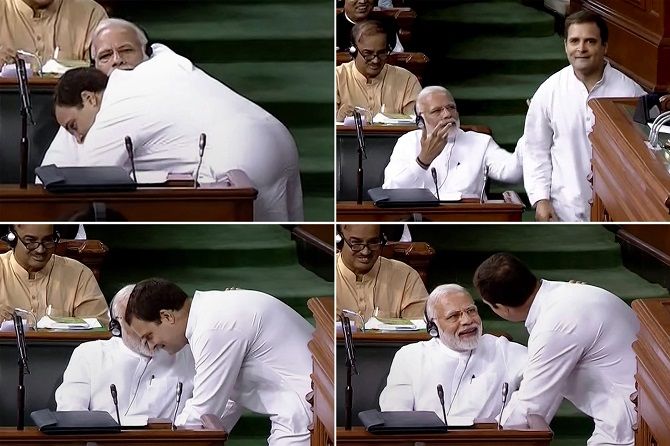

Yet, ultimately, that infamous forced hug and the wink that followed it went to prove the truth of what the prime minister derided as his 'childishness' in another context. It was impossible to get rid of the feeling -- buoyed by the prime minister's painting of the motion as little more than an anti-Modi stratagem -- that Gandhi was in the House just for kicks.

Gandhi has been in the public eye for many years now, so it is baffling that he can still get up to the kind of antics he displayed in Parliament. One wonders if the hug-and-wink were aimed at bolstering the otherwise dilute constitution of his speech.

Riddled with generic arguments against the government, it failed to make an impact. The one point of specific criticism that he lobbed, pertaining to Rafale, backfired too.

One argument that the Congress repeatedly presents against the government -- and Gandhi included it in his speech -- is the infamous rejoinder made by Amit Anilchandra Shah in a 2015 interview to Modi's promise during the 2014 election about bringing home the black money stashed abroad.

The word Shah used -- jumla -- is now part of the Opposition's established jargon for criticising the government on any matter.

This has diminishing returns.

One, in public perception, Modi's record on black money -- from demonetisation to GST to the IBC -- is arguably more muscular than his inability to fill every bank account with Rs 15 lakh, which does -- and should -- sound like a metaphor for cleaning up the system.

To continue to flog this horse as if it were a realistic promise may not be the smartest strategy.

The prime minister, on the other hand, came prepared for the debate with data on his government's schemes, and spoke with a natural flourish that the Gandhi scion sorely lacks.

What must have particularly galled the Congress was Modi's shrewd portrayal of that innocuous, if ill-timed, hug as an expression of Gandhi's tearing hurry to occupy the prime minister's chair.

It is this difference in their personalities -- one in eloquent command of the requirements of Parliamentary debate, the other unable to infuse spontaneity in his script -- that will be as much a factor in who India votes for next year, as other more germane factors.

Gandhi recognises this and has gracefully complimented the prime minister on the latter's superior communication skills.

But he needs to do more. The Congress is keen to insinuate that their leader has been travelling the length and breadth of the country over the past few years and that this endeavour has given him a deeper insight into the issues that plague Indians.

But during speeches, Gandhi does not emanate the confidence that such large-scale travel should give him. The impression that he remains reliant on notes to speak on the most basic aspects of policy-making is hard to shake.

In contrast, the prime minister leaves no opportunity to remind the nation that he was an ordinary party worker for many years before he assumed power, first in Gujarat and then at the Centre.

In Chhattisgarh recently, to inaugurate an extension to the Bhilai Steel Plant, he spoke at length about his love for the region, developed over the many years he spent there as a young RSS pracharak.

During the no-confidence speech, the prime minister furthered this divide between himself as a grassroots man and Gandhi as belonging to the elite by bringing up, not for the first time, the naamdaar-kaamdaar dichotomy.

Paradoxically, for one of the most powerful leaders of his party and of the country, Modi is able to attach a penumbra of truth to this assertion because of his willingness to thus deprecate himself.

The wink played into this impression.

If Gandhi had not returned triumphantly to his seat after the hug and, in particular, not chosen such a brute measure to celebrate his triumphalism, the prime minister's subsequent remarks about the hug would have seemed churlish and in bad faith.

In this event, the wink frittered away the hug's goodwill and Gandhi, once again, gave reason for criticism inside the Parliament and lampooning outside.

The no-confidence motion is said to have sounded the poll bugle for 2019 in earnest. The Opposition is raring to band together to take on Modi.

What they must also focus on is choosing a face to whom theatrics and verbal pyrotechnics come as naturally as they do to the prime minister.