Though launched in 1996, the slum replacement scheme has more or less bombed. Builders have not found the slum spaces attractive enough to build, harvest extra FSI for sale in open market thereby subsidising the rehabilitation, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

Though launched in 1996, the slum replacement scheme has more or less bombed. Builders have not found the slum spaces attractive enough to build, harvest extra FSI for sale in open market thereby subsidising the rehabilitation, says Mahesh Vijapurkar.

How far would the extension of the slum cut-off date to January 1, 2000 from January 1, 1995 take Mumbai towards a slum-free status? Probably not much, not even as far as you can throw an elephant with your left arm.

There are three reasons why. One, the free slum replacement housing for the pre-1995 slum dwellings has hardly moved an inch since the 1996 effort. Two, the government is confused. Three, the real estate developer’s lobby has its way.

The slum dwellers are, at best, beneficiaries of an assurance that their dwellings, if built prior to 2000, will not see their occupants evicted and structure razed. Much like the most of the pre-1995 slum dwellers have, they would feel reassured.

However, till they are converted into vertical replacements housing on the slum lands, the occupants won’t have a title to it, though, as per a new law, post-cut-off acquisition by a person of pre-1995 vintage, and now also pre-2000, can be validated for a fee and assured of rehabilitation.

Let us go by the order listed earlier. One, though launched in 1996, the slum replacement scheme has more or less bombed. Builders have not found the slum spaces attractive enough to build, harvest extra FSI for sale in open market thereby subsidising the rehabilitation.

A long list of slum rehabilitation schemes cleared have been in the limbo though the builders and developers have entered into contracts with slum dwellers. They are, as it were, squatting on slums lest it slip into some other developer’s hands. Barely four to five per cent of slum dwellers have benefited so far.

Two, the government is unable to arrive at a simple, endurable scheme and set the rules for all times to come. Depending on locations, the politicians in power or with influence, the rules -- FSI, the permission to carry the transfer of development rights to another favourable location though raised from the slums etc -- keep changing.

Three, the influence talked about is what is wielded by the builder-developer lobby through the medium of the politicians. The rules have to be conducive to their interests or else, the project stalls. If anything, apart from jacking up real estate prices, this lobby ensures, as collateral, housing scarcity. Scarcity is what drove the city into slums.

Many of these slum pockets may have had faced the hurdle of unprotected slums built after 1995 and up to 2000 being amidst them, and when these newly protected slum dwellings’ turn comes, they would be having the post-2000 slums, thus forming a bottleneck. The builders are the most inconvenienced by this.

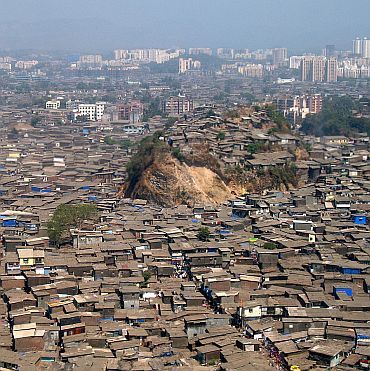

The commitment to rid the city of slums, with whose inhabitants’ help this city runs, has been at best casual. The addition of about three lakh slum dwellings by extending the cut-off to 2000 to the 10 lakh pre-1995 units does not yet cover the entire city’s slum dwellings. It may be covers about between about a third and half.

None has ever asked this simple question: what about the rest?

Already, a discriminatory approach is in the air. State Housing Minister Sachin Aher has said that it was no longer within the means of the government to fund free replacement housing, which is incorrect. The government is a facilitator, not an executor of the policy.

The slum dwellers that form the post-post 2000 cut-off component will have to share the costs under the Rajiv Awas Yojana but have to settle for moving from their locations to other places within the city. The location is a vital determinant of a slum’s existence.

Probably, if this RAY, not implemented in the city so far, were to gain traction, the prized real estate would be lost. The slums dwellers would remain in situ, robbing the real estate of its opportunities. Look at any slum, it is wonderfully located -- access to various points in the city, close to work opportunities.

In the 2004 elections, the Congress had promised this extension, but between that and the 2009 elections, committed by an affidavit in the Bombay high court, that it would not do so. When pointed out in 2009, the promise was explained away as “a printing error” and allowed to rest.

The fear that the courts would make them contemnors lurked in every politician’s and bureaucrat’s mind but with the likely advent of the Aam Aadmi Party on the scene in Mumbai for the Lok Sabha polls, with its quick-fix housing plank of greater appeal, the risks were weighed and taken.

A high court order had allowed carrying of transfer of development rights (TDRs) harvested from a slum rehab project to another location for better marketability, “considering the cut-off date as 1.1.1995 shall not be extended further”. This and other issues figure in a clutch of petitions being heard in the Supreme Court.

The confusion is on display in the statement of objectives of the bill pushed through on the last day of the recent legislative session. It speaks of the need for “survey and review of existing position” for “achieving the objective of rehabilitation of slums”. It does not, however, explicitly say freeing the city of slums has slowed down.

Though it talks of the state government is “required to take all such measures in slum areas which will improve the provisions of water supply, drainage and sanitary conveniences, facilities for disposal of waste water”, these are precisely the areas most neglected.

Earlier, only the notified slum secured any benefits, and post-1995, only those that were declared protected. Then only squatters on civic and government lands enjoyed the possibility. And even in such areas, they are grossly inadequate. Only recently did the civic body decide on an in-principle policy that all should get water, regardless of their status.