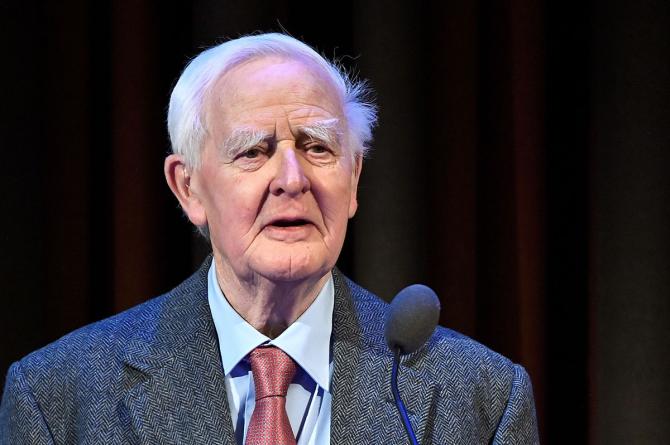

He will be remembered not only as a writer, but as one of the great chroniclers and interrogators of the history of our times, says Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar, as he mourns the passing of a legend in this must read tribute.

When somebody once asked late Yevgeny Primakov, former head of the KGB -- and former prime minster of Russia -- who he identified with, he replied 'George Smiley', John le Carre's immortal cold-war era master spy.

At the KGB training schools, le Carre's books were essential reading.

Unlike Ian Fleming's creation James Bond who became in popular imagination the archetypal modern spy, le Carre's spies have a universality of a different sort.

Smiley stands out as the greatest anti-Bond creation of the entire cold war literature.

Le Carre had the following explanation for this phenomenon: 'You know, in the end -- and it applies to doctors, scientists, and it applies to spies -- people who are using the same techniques, developing the same techniques, who have the same attitude towards human beings, who put expediency and outcome over method, they are a brotherhood or sisterhood or what you will...

'It's a shared attitude that creates this masonry.

'And it's very spooky.

'And it can also be profoundly disconcerting...

'But nevertheless, we are in some spooky way colleagues.'

However, the only common link between Bond and Smiley must be that both were devoted to Queen and country.

Bond epitomises the myth of spies as the glamorous, exciting, handsome guy, suave and urbane, who has a way with women and can be trusted to outsmart his adversary when the crunch time comes.

But 'podgy' Smiley knew his wife Ann was unfaithful.

Le Carre's spies are lonely, disillusioned men who worked on meagre shoestring budgets, vulnerable to bureaucratic wrangles and power play, victims of callous politicians, caught up in a moral dilemma as to whether the ends, even if acceptable, really would ever justify the devious means -- entrapped, in the final analysis, in a twilight zone between right and wrong.

They belonged to the real world of espionage, reeking with the stink of whiskey, cigarettes and paranoia.

Le Carre drew profusely from his own kind: men from broken homes who advanced in life through the grand chambers of the British establishment -- public school, Oxbridge, the army, the Foreign Office -- whose mouths turn the truth to quicksilver, whose authenticity is never certain, whose tactics of evasion and deception are necessary weapons, and all the while innately given to a seething distaste for the bigotries and prejudices of the English ruling classes.

In The Secret Pilgrim (1990), Smiley gives a speech to young MI6 recruits in which he reminds them that 'the privately educated Englishman ... is the greatest dissembler on earth.... Nobody will charm you so glibly, disguise his feelings from you better, cover his tracks more skilfully or find it harder to confess to you that he's been a damned fool.' (Doesn't this become an apt description of Boris Johnson and his circle?)

Le Carre's novels stand out as an outstanding record of the nature of bureaucracies.

He is at his best in his ruthless exposure of English cynicism, of the passionless and the flippant in a society adrift, guided by the privileged and unserious, desperately searching for some kind of redemption.

But he refused to pass moral judgment.

His spies (and the Soviet-bloc spies) were morally compromised cogs in an indifferent, even cruel, wheel that kept rotating, and were abandoned to tackle in their own ways the lurking treachery and betrayals, the dangers and imponderables of their trade, whilst also encountering demons within or struggling with personal tragedies.

That's why le Carre's spies were never too sure who their real enemies were -- their own back-stabbing treacherous, slimy colleagues whose subterfuge, role play and dishonesty could be lethal -- or the Soviet enemy.

The denouement in his novels often leaves a sense of incompleteness, of human frailty and the emptiness that accompanies winning.

In a masterly 1999 essay in The New Yorker magazine titled The Real le Carre, British historian, author and commentator Timothy Garton Ash wrote, 'Thematically, le Carre's true subject is not spying.

'It is the endlessly deceptive maze of human relations: The betrayal that is a kind of love, the lie that is a sort of truth, good men serving bad causes and bad men serving good.'

No wonder, le Carre's works -- especially, his great espionage novels of the 1960s and 1970s -- leave an overpowering feeling of elegies laden heavily with a certain inchoate sadness stemming out of conflicted loyalty and spoiled idealism.

Le Carre is superb in capturing the loneliness of the double agent -- duplicitous and loyal only to himself.

His own brief passage through the secret world of MI5 and MI6 meant that he didn't have to search to comprehend that there are traitors in one's own ranks or that the institutions one is fighting to preserve might not be worth the struggle after all.

His wonderfully labyrinthine novel A Perfect Spy (1986) has been called one of the finest English novels after World War 2 -- the story of Magnus Pym, an English double agent on the run after betraying secrets to the Czechs.

British intelligence officers are searching for Pym who is hiding out in Cornwall, where he has embarked on a quest to understand fundamental questions about his father and about what let him to betray his country.

To be sure, le Carre was a man and writer of multiple contradictions who nurtured deep resentments and class insecurities going back to childhood, although like a typical member of the English establishment, he was educated at Sherborne and Oxford and taught as a young man at Eton, the 'spiritual home' of the English upper classes.

Indeed, he knew the codes, the interconnections that existed (and still exist) between the great schools, Oxbridge, Whitehall, Westminster, the Inns of Court, the BBC and Fleet Street, the gentlemen's clubs and the City.

But such impressions are never reliable when it comes to capturing the inner life of someone as complex as le Carre.

Thus, he refused all official honours, including a knighthood and never allowed his novels to be entered for literary prizes.

Certainly, le Carre became angrier with age, raging against the Iraq War (2003) and the rapacity of multinational corporates, and has been accused of being anti-American and anti-Israeli.

No matter his private turmoil, le Carre will be remembered not only as a writer but as one of the great chroniclers and interrogators of the history of our times.

Le Carre's contempt for American foreign policy comes out vividly in A Perfect Spy, his most autobiographical novel.

In that book, as well as in his classic Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy, it was the imperious designs of the US, as opposed to Soviet communism, that represented the true threat to the world.

Diplomacy and espionage are two sides of the same coin.

Any diplomat who has served in the former Soviet Union will be indebted to le Carre for his portrait of that great country on the edge of complete moral breakdown, and his deeply insightful psychological account of the relationship between Russia and the West during the decades of the cold war.

Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar served the Indian Foreign Service for more than 29 years.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com