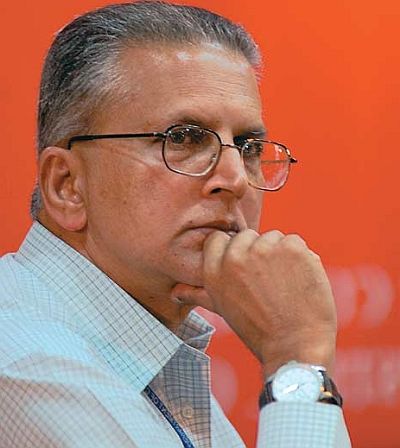

'Even though he knew full well that the manipulation went against the facts as he knew them, G K Pillai nonchalantly contented himself with stating that since the file came from the minister himself, he just passed it on as it was.'

'Even though he knew full well that the manipulation went against the facts as he knew them, G K Pillai nonchalantly contented himself with stating that since the file came from the minister himself, he just passed it on as it was.'

'In the '60s even the junior-most officer never hesitated to express himself boldly and frankly in meetings and notings, and even to the extent of recording his disagreement with the views of their superiors.'

'The spirit pervading bureaucracy in those halcyon days was one of fearless expression of views and elders in service and ministers took it with understanding and good will,' says B S Raghavan, the distinguished civil servant who once served at the home ministry.

The print and electronic media, as also the social media, are full of reports of the manner in which a solemn and sacred document like an affidavit to be filed before a temple of justice suffered manipulation bordering on falsehood and forgery at the highest levels of the ministry of home affairs.

When G K Pillai, home secretary at the relevant time, was asked why he did not object to the rewording of the affidavit in the Ishrat Jahan case by the then home minister P Chidambaram, even though he knew full well that the manipulation went against the facts as he knew them, he nonchalantly contented himself with stating that since the file came from the minister himself, he just passed it on as it was.

The home ministry was the morphed version of the political department of the days of British imperialism and it was the direct charge of the viceroy and the governor-general.

For many decades after Independence, it was regarded as the pivot of the Union government responsible for many areas such as recruitment, appointment and deployment of the highest services of the land, including the judges of the high courts and the supreme court, internal security, Centre-state relations, administration of preventive detention act and Defence of India Rules, Emergency, President's rule, the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Intelligence Bureau in its full panoply, including external intelligence, border security, paramilitary forces -- in short, areas at the heart of the nation now hived off into two or three separate ministries with their own hordes of ministers and functionaries.

In the 1960s when I served for ten years in the ministry, first as deputy secretary and then as the director, there was the Cabinet minister, two ministers of state, one secretary, two additional secretaries, five joint secretaries, one director, nine deputy secretaries and 10-12 under-secretaries.

Those working in the ministry were proudly conscious of it being a cornerstone of the Constitution and tried to conduct themselves in the highest traditions of public service.

Never once even the faintest glimmer of any thought of fabrication, falsification, manipulation or tampering in any manner with any facts or documents ever crossed our minds even momentarily.

On the contrary, even the junior-most officer never hesitated to express himself boldly and frankly in meetings and notings, and even to the extent of recording his disagreement with the views of their superiors.

Compare G K Pillai's attitude with how those working in the home ministry construed their role and duty to be in those far-off days, as will be evident from the following narrative.

Following the Chinese aggression of October 1962, a section of the Communist Party (there was only one in those days) was reported by the Intelligence Bureau to be propagating the Chinese line and pitching for a negotiated settlement.

The IB, which was exercising surveillance over the Communists, forwarded a list of around 1,200 persons (dubbed pro-Chinese Communists) who were said to be aggressive in espousing the Chinese cause and who, therefore, according to the IB, posed a danger to national security.

Home Minister, Gulzarilal Nanda called a meeting of the home secretary, the intelligence chief and other senior officials concerned to discuss the IB report. I was also present, but being the junior-most officer, I was there merely to keep notes and record the decision for further processing.

After a detailed analysis of the pros and cons, the unanimous view of the assembled officials was to act as per the IB's recommendation. It was now for me to initiate the concomitant steps: Prepare the warrants of detention, and alert and line up the state chief secretaries and inspectors general of police to be in readiness to complete the entire operation in a synchronised manner so as to guard against anyone going underground.

I returned to my room with great uneasiness. After all, it was I who would be signing and issuing the orders of detention: So, should I not also be fully convinced that the course of action decided upon was the right one?

Somehow, my conscience rebelled against condemning honest dissent as prejudicial to security and defence of India.

After all, to argue that India should enter into a dialogue with China in an accommodating spirit was not a crime. Even if some of the apparatchiks had said in secret meetings that India was in the wrong in provoking China, I saw nothing objectionable in it.

Further, if the government went in for wholesale detention, it would lead to a further hardening of their stand and might even make militants of some of them.

Finally, what was the proof that these 1,200 members were indulging in anti-national activities? We only had the word of some constables covering the meetings incognito, who might or might not be able to grasp the sense of what was being said.

I decided to put down all these reservations in a note and send it to the home secretary, L P Singh. Remember, a final decision had been taken after due deliberation by a conclave of officials at the highest levels of the government presided over by the home minister himself and also remember, I had no business at that point to be raising objections.

The home secretary, on receiving my note, could have promptly sent it back peremptorily ordering me to carry out the decision already taken: or, worse, he could have thought that I myself was a pro-Chinese Leftist mole in the sanctum sanctorum of the home ministry and got me reverted to Bengal, or in the worst case scenario, had me detained, if not dismissed from service, under the security clause of the Constitution without proceedings and inquiry.

To the contrary, while he disagreed with my contentions and wanted the decision to stand, the home sercretary did me the courtesy of rebutting each of my arguments with reasons and sending the file to the home minister with the remark, 'The Deputy Secretary has expressed his reservations, ably supported by arguments, about the decision taken last evening in HM's room. For the reasons I have mentioned, I feel that the decision is the right one and should be implemented. Still, I am bringing the DS' note to HM's attention as it is well worth reading.'

Nanda, too, could have just initialled and sent the file back. No! He sent it to Lal Bahadur Shastri with his own words of praise for the way I had argued my views. Shastri noted in his beautiful hand to the effect: 'I appreciate Raghavan's effort to put down his views. However, for the reasons mentioned by the HS, we may go ahead with implementing the decision.'

These appreciative observations did not relieve me of my uneasiness on another count. The names of Jyoti Basu, Harkishen Singh Surjeet, A K Gopalan, Susheela Gopalan, and E M S Namboodripad were included in the list.

In my opinion, their patriotism could not be doubted and they were second to none anywhere in the world in their stature, calibre and service to the country. The very thought of detaining them on an atrocious and unprovable pretext went against my grain.

So, I sent the file back once again to the home secretary expressing my views to the above effect. This time, my stand was approved right up to the PM's level, and they were left out of the list of detenues.

Can you imagine a mere deputy secretary surviving what would be straightaway condemned as insubordination and disloyalty if only he had been serving political dispensations in recent years?

The spirit pervading bureaucracy in those halcyon days was one of fearless expression of views and elders in service and ministers took it with understanding and good will.

If they differed, they had the self-confidence to over-rule you in writing on files, giving their arguments, unlike the present political bigwigs who are allergic to any dissenting opinion.

Civil servants too did not feel that they were doing anything heroic or unusual. They took intellectual integrity and freedom to give their views as part of a natural order of things. It never impinged on their consciousness that there was any other way.

B S Raghavan is a retired IAS officer who served as the Director, Political and Security policy planning, in the home ministry between 1961 and 1969, and headed the National Council Secretariat under Jawaharlal Nehru, Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi.