'How can the police, especially the Gujarat police, earn their laurels if they stick to the rule book?' asks lawyer Susan Abraham.

Tushar Kanti Bhattacharya's arrest on the early morning of Tuesday, August 8, as he was alighting from the Gitanjali Express returning home to Nagpur traversed many rules of criminal jurisprudence.

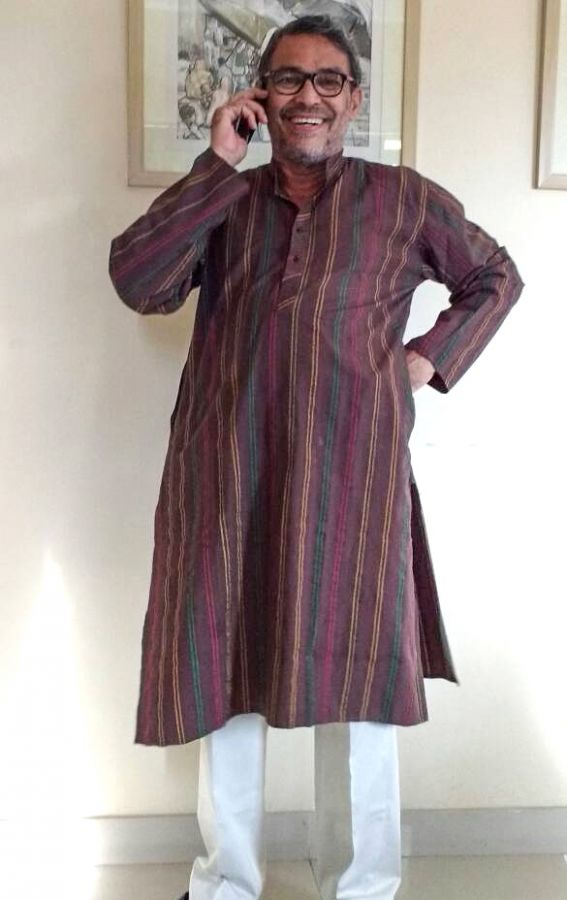

The 62-year-old semi-invalid -- he suffers from a chronic back ailment -- was arrested by the Gujarat police and whisked off to Nagpur airport to be taken on a flight to Surat.

Was he a fugitive?

An outlaw?

An absconder from a case?

None of these.

Bhattacharya was leading a normal middle class life with his wife Dr Shoma Sen, head of the department of English literature at Nagpur University, spending most of his waking hours doing freelance writing in Hindi and translations, being equally prolific in Hindi and English.

He was returning home to Nagpur from Kolkata after a longish stay with his government employee sister to rally legal help for his brother Aseem Bhattacharya who was lodged in Alipore jail in Kolkata.

He was not allowed to contact Shoma, or return home, and at the moment, his whereabouts are unknown.

By law, the Gujarat police ought to have sent a summons to the openly known address of his residence at Nagpur to appear before the concerned court and case in Gujarat.

Bhattacharya would have been able to make arrangements for his bail and presented himself without all the hungama (fuss).

But how can the police, especially the Gujarat police, earn their laurels if they stick to the rule book?

If the abduction was not brazen enough, what is more shocking is the case in which Bhattacharya was kidnapped by the Gujarat police.

It happens to be Crime Register No I-37 of 2010 with the Kamrej police station, Surat.

Bhattacharya is the 22nd person arrested in the case. All the 21 others have been released on bail.

This was another reason why the modus operandi -- abducting Bhattacharya -- from Nagpur was totally uncalled for.

The sections registered in the case against all the accused are, of course, serious in nature.

No less than Sections 120(B), 121(A), 124(A), 153(A) (B) of the Indian Penal Code and Sections 38, 39 and 40 of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (amended in 2004 as the freshly minted anti-terror law after the successive repeal of TADA and POTA).

Some of the mandatory fields in the First Information Report registered by the Kamrej police station on 26.2.2010 reads like straight out of a Kafka novel.

Time - Any time till today.

Nature of offence - Creating of class conflict, and rousing feeling of dissatisfaction among religious minorities and tribals living in the forests by doing misleading propaganda, causing anti-national sentiments and so on.

Names against whom the FIR was lodged - Unknown members of CPI (Maoist) and others.

The background to this case is equally Kafakesque.

In the spate of arrests that took place all over the country post-2007, with the then UPA governments declaring Naxalism to be the 'biggest internal security threat', there were a spate of arrests in urban centres all over the country wherever the Maoists were leading struggles in adjoining rural areas.

Modi-led Gujarat, not to be left out of the reckoning on the map of curbing Maoists (which, of course, came with meaty budgetary allocations), created a case which as the Gujarat high court later observed was 'roving in nature'.

In fact, Justice Anant S Dave, while granting bail to the other accused in the case in Criminal Miscellaneous Application No 12435 of 2010 in Vishvanath @ VishuVardhrajan Aaiyar vs State of Gujarat in order dated 18.10.2010, noted 'forming a union or carrying out a movement in respect of labourers or tribals of the area to protect their statutory right as well as fundamental rights under the Constitution of India against a section of influenced and established group of the society and expression of anger or even writing or authoring any document or material or a book, cannot be considered as an anti-national activity amounting to waging a war against the nation.'

The most bizarre turn of events is this. Tushar Bhattacharya was already an undertrial in Cherlapally jail, Hyderabad, when the FIR in C R No I-37 of 2010 was registered on 26.2.2010.

He surely could not be accused of being a Houdini and committing the offence from behind bars!

The last and most incriminating part of the police kidnap drama is that Bhattacharya, while an undertrial lodged in Cherlapally jail, Hyderabad in 2010-2013, had made not one but two applications to the court of the judicial magistrate first class (JMFC), Khattor, under whose jurisdiction the case was lodged.

Having learnt that his name figured in the chargesheet, he plainly asked to be produced in the court as an accused if that really was the case.

The two letters are dated May 9, 2011 and July 22, 2011.

Why did the same Gujarat police not show any alacrity in having Bhattacharya produced in the court then?

In fact, Kobad Ghandy's name also figures in the same case.

Ghandy, a well known political activist who has been an undertrial since 2008 and is currently lodged in the Vishakapatnam central jail, has also written letters to the court of the JMFC, Khator to be produced in the case, but he too has not been produced in the case by the Gujarat police.

The Gujarat police knows fully well that Tushar Bhattacharya and Kobad Ghandy will eventually get the benefit of the bail order granted by the Gujarat high court to the other accused in the same case.

Why then this drama over Bhattacharya's abduction?

Does it have something to do with a desperate Gujarat government wanting to whip up some more nationalist frenzy through its media about persons unknown to the people of that state being nabbed as dreaded Maoists?