'Our prime minister manifests a vision for India to be great and powerful, but the modernity required -- of thinking, attitudes, behaviour -- seems alien, if not abhorrent, to his constituency and associates,' says Ambassador K Shankar Bajpai.

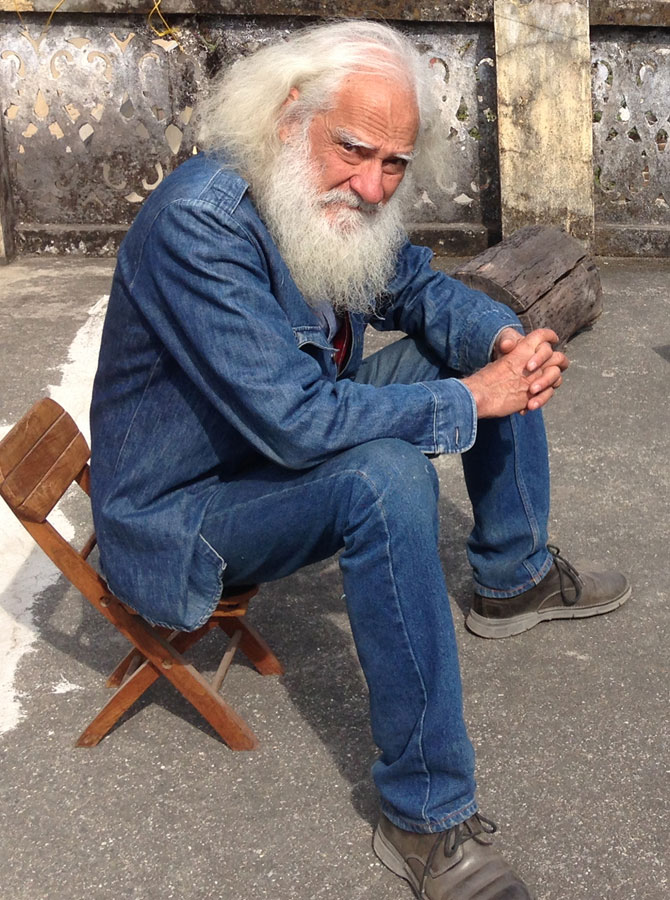

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

Is 2017 another anniversary of 1947, or a turning point?

India at 70 differs widely from what it was and what most founding fathers envisaged. The Constitution they gave us on Republic Day 1950 suited their vision, but has changed comparably.

Will it witness a 70th birthday, or be shorter-lived de jure, as it has been de facto?

Similar questions arise everywhere.

All governments fail their people's expectations, but in democracies the very beliefs, principles and practices long considered Democracy's essence are endangered.

The worst horror is intolerance: No 'decent respect' for any difference; brute force suppressing reasoned discussion; law contemptuously disregarded; bigotry spurred by demagoguery -- such ugly forces multiply worldwide, not least in Western countries long claiming exemplarity of openness.

When the 'world's oldest democracy' succumbs, the whole system's vulnerabilities show alarmingly.

Authoritarianism fares no better, but its appeal increases. Making democracy work should be today's prime concern, but most people start preferring anything that delivers.

Our democracy is more vulnerable because the essential foundations never firmly settled. Balfour said the British parliamentary system worked because, despite deep differences, 'there is a fundamental agreement among all to make it work' -- plus some mutual respect and accommodation.

Disappearing everywhere, these conditions never took root here. The spirit essential for the 1947 system doesn't exist.

That too has similarities worldwide. Bitter gridlock from poisonous party-relations substantially caused the Trump phenomenon.

How America, manifesting such impressive self-improving maturity in choosing a black president eight and four years ago, has changed so startlingly so fast needs studying, but our first worry must be ourselves.

Not one institution or instrument of State functions properly. Legislatures meet minimally, providing neither laws nor oversight; judiciaries fumble along, often addressing what should not be their business (a Supreme Court running cricket?) while the wait for justice skyrockets; the executive, both political and permanent reinforce each other's failings, in disarray; while the fourth estate, so vital to Democracy, blithely undermines it.

Government-Opposition relations are practically non-existent, the party that led us into Independence now meanders devoid of ideas, leadership and prospects.

Problems intensify as our apparatus for handling them degenerates.

Outside government is no better: in all professions, schools, hospitals, businesses, sloppiness grows -- and nothing is done.

India 70 years ago looked different, though the germs started work straightaway.

We were the most advanced of decolonised States, respected for efficiency, seemingly imminent promise, above all as a democratic model.

Others sent us soldiers, diplomats, doctors etc for training, now we need them.

Put an Indian anywhere abroad, (s)he excels, at home is stifled. Must extending entitlement debase quality, or has our approach been wrong?

We blame our deficiencies on colonialism. Colonialism was an obscenity, but should we not ask why we succumbed?

No great Armadas, no thundering hordes, invaded us, a handful of adventurers bested us -- even in intrigue.

Our faults defeated us: Arbitrary fiat and obsolete, cocksure obscurantism succumbed to the colonisers' discipline, organisation, systematic attention to duty, objective assessment, above all their use of new knowledge.

Neither more intelligent nor virtuous, even while fortune-making they managed to subordinate the personal, using State power for State purposes.

The State, leave alone national purpose or progress, means nothing to us, the personal is paramount.

Many nationalist leaders did realise this must change, initiating the 1947 effort to make India modern.

Rejecting that, we have steadily reverted to old ways: Recidivism triumphs over modernity.

Openness to using advances in knowledge to improve society and life is modernity. With us, obscurantism preempts any such driving force.

Our prime minister manifests a vision for India to be great and powerful, but the modernity required -- of thinking, attitudes, behaviour -- seems alien, if not abhorrent, to his constituency and associates.

Can they articulate any vision of our future -- or realisation of present challenges?

Worse, the considerations determining the decisions shaping our daily lives are unworthy of the issues involved -- petty, selfish, myopic.

Similar defects infect all governments, but serious ones let some broad, reforming, forward-looking vision have play.

The most destructive backwardness in Third World States, particularly distinguishing them (till recently) from advanced countries, is the absence of any sense of national purpose, as distinct from personal or group benefit.

The witticism about our economic sluggishness attributed it to 'the Hindu rate of growth.' There must be a Hindu rate of decline also: We have taken decades to reduce ourselves from First World objectives -- or capabilities -- to Third World practices.

India was once well called the Asian bridgehead of the Enlightenment: Respect for Reason, the ideas of the great progenitors of liberal democracy, informed our aims, practices, public discourse as in no Afro-Asian country.

Japan has been unique -- not least in deliberately choosing modernity ever since Commodore Perry's ships shocked it out of its old ways (while retaining its distinctive culture).

China also now rises all the faster for having opted for modernity, albeit authoritarian.

We meanwhile relapse into the failings responsible for our colonisation: Internal squabbling, personal/clan interest superseding nation or society, sloppiness, unprofessionalism.

And then corruption.

Whether 'demonetisation' is good or bad economically, time will soon tell, but it cannot affect the real corruption.

All misuse of position for illegal personal gain is disgraceful, but countries can survive, even advance, under corruption that gets things done: It is the bribery inescapable from meeting ordinary, daily needs that is the metastasising cancer.

Try getting, without paying, your driver's license, house plans passed, property transfer registered, school admission -- the list is endless.

We who pay are also guilty, but the way we run our affairs makes honest living nightmarish. Previously, redress was possible by appealing to senior officials, now they too are no better, or helpless.

Everyone knows the malady, not one hope of cure is discernible.

If what you have doesn't work, something must replace it or you suffer.

One greater alternative would do it: Get together to make it work.

That being a dream, what reality will replace the dream of 1947?

K Shankar Bajpai is a former ambassador to Pakistan, China and USA, and secretary, ministry of external affairs.

DON'T MISS reading the features in the RELATED LINKS below...