New Delhi has repeatedly missed opportunities for political engagement in Kashmir in the past.

New Delhi has repeatedly missed opportunities for political engagement in Kashmir in the past.

It must seize the next one, says Ajai Shukla.

Kashmir has completed over 100 days of public protests that began on July 9, a day after the Jammu and Kashmir police killed Hizbul Mujahideen 'commander' Burhan Wani in an encounter.

The agitation leaders, including hard-line separatists like Syed Ali Shah Geelani, ensure the Kashmir valley remains locked down, except for a two-hour period each day when the bazaars open and the streets thrum with life.

Kashmiri agitators insist they will not relent until New Delhi meets conditions that no elected Indian government can.

Meanwhile New Delhi, labelling all this as Pakistan-backed mischief, continues a tough line.

Paralysed in this crossfire is J&K Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, heading an ineffectual coalition between her People's Democratic Alliance and the Bharatiya Janata Party.

The PDP-BJP coalition was billed as a bridge between New Delhi and Srinagar, but that chasm remains as wide as ever.

Angry Kashmiris insist they will continue agitating indefinitely -- something they clearly cannot do.

New Delhi, equally unbending, is focusing on isolating Pakistan.

Yet, when New Delhi can reach out to Kashmiri separatist leaders without losing face, and after demonstrating the punitive cost of confronting the Government of India, there will inevitably be a truce, even if temporary.

Translating that temporary reprieve into an enduring peace would require New Delhi to recognise Kashmir as an issue that demands concerted political engagement, not just a security issue that requires the application of sufficient force -- as New Delhi has repeatedly done.

The strong arm of the State can manage periods of instability. Yet, without political management, normalcy will prove short-lived.

The security situation in J&K is a fluctuating variable, which is linked to New Delhi's political engagement with Srinagar and Islamabad.

Security is gauged from four indicators -- the number of militants, security force personnel and civilians killed each year, and the number of militancy-related incidents.

From 1990, when the Valley went up in flames and thousands of young, gun-wielding Kashmiris took control of the streets, the army began relearning counter-militancy operations, which it had honed in the Northeast.

The difference was that the Kashmir uprising was openly sponsored by Pakistan and, after the Hizbul Mujahideen supplanted the J&K Liberation Front, was imbued with a strong religious fervour.

By 1996, the army -- partly through a new counter-insurgency force, the Rashtriya Rifles -- had reasserted control to the level that the 1996 general elections in Kashmir could be credibly held.

This was the first moment of opportunity. However, New Delhi had a series of weak Union coalition governments that failed to follow up with a political outreach.

That lost opportunity was followed by five years of turmoil in J&K, including the Kargil conflict, stepped up militancy and an almost-war in 2001-2002, when the National Democratic Alliance government deployed the army for war after a Jaish-e-Mohammad attack on Parliament House in New Delhi.

This period saw the highest casualties of the J&K insurgency.

Yet, inevitably, peace kicked in at the end of 2003 with a ceasefire on the Line of Control and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee's memorable outreach to Kashmiris under the ambit of 'insaaniyat,' or humanism. While representatives of President Pervez Musharraf and Mr Vajpayee hammered out a 'Four-Point Formula' for permanent peace in J&K, and cross-LoC movement and trade began, the security forces exploited this peace through the construction of the LoC counter-infiltration fence.

However, with no public political engagement with J&K, Mr Musharraf's political decline and eventual ousting brought this house of cards tumbling down. This was the second lost opportunity in Kashmir.

The period 2008 to 2010 saw three bitter years of turmoil in the Valley. In what some call the 'first Kashmiri intifada', a hitherto politically disengaged generation of Kashmiris was effectively radicalised, taking up the mantle of the Azaadi (freedom) struggle.

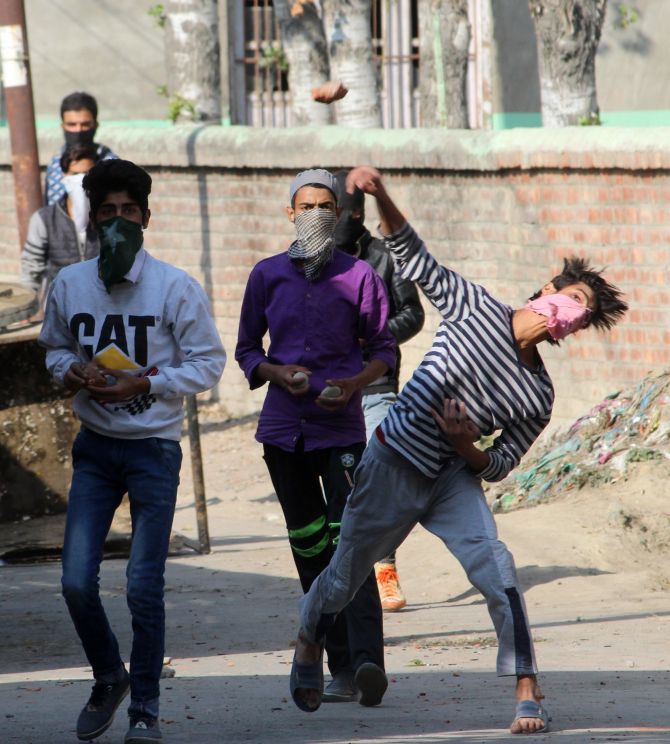

With intense military operations continuing to take down militancy, that ceded primacy to stone-throwing street protests that (ironically) deploy the moral ascendancy of 'non-violence.'

2011 to 2013 saw another interregnum of peace, through a 'winning hearts and minds' campaign fashioned by the army's innovative commander in Srinagar, Lieutenant General Syed Ata Hasnain.

With initiatives like 'Jan Sunwai' (public hearings), and the wildly popular Kashmir Premier League cricket tournament, this created a moment of political opportunity that, like the previous two occasions, was ignored by New Delhi.

In 2014, the inevitable downswing began. Although violence figures grew only slowly, there was palpable Kashmiri anger at the majoritarian politics in other states, evident in the beef ban, ghar wapasi and the love jihad bogey.

With no political outreach to Kashmiri separatists, resentment began manifesting itself through unprecedented confrontations with armed military units, including attempts to break army cordons laid around villages where militants were holed up.

The mass uprising following Burhan Wani's death had been brewing for two years. But, when Kashmiri resentment and anger have played out, a fourth moment of political opportunity will inevitably present itself.

It is for the government to grasp it.

IMAGE: Kashmiri youth throw stones at the police, October 21, 2016. Photograph: Umar Ganie