'For Nitish Kumar the message is to be democratic. With the support of the BJP, he had suppressed criticism in Bihar. He would also need to change his highly authoritarian way of governance.'

'The Grand Alliance, given the decisive mandate in its favour, cannot afford to fail the people. They have a duty to make it a model for the rest of India,' says Apoorvanand.

'The people of Bihar have shown that they are not communal and that they are literate,' read a Facebook post of a school teacher who is also a Muslim woman after the trends of the election results of Bihar firmed up. Her Facebook history shows that she is a normal, apolitical, if not non-political, person who defines her life within the circle of her family and friends.

On Sunday, November 8, when some television news channels started predicting a comfortable victory for the Bharatiya Janata Party, a middle age housewife, again a Muslim, hovering around the television set, asked her husband, 'Does this mean we'll have to live in constant fear now?'

"Assalamualaikum," was the early morning greeting I received when my phone rang the next morning. On the other side was a friend, currently in the US. He is not a Muslim, but he belongs to the much maligned community of those who are now officially called 'sickulars' by the BJP and its friends, against whom a leading Bollywood actor organised a march in Delhi a few days back.

A day before the results, a friend, again a non-Muslim, and a hardened professional journalist who does not like to be called 'secular' told me that it was necessary for the BJP to be defeated in the Bihar elections for the profession of journalism to get breathing space to revive itself in its integrity.

An auto driver from Bihar told a research student of mine that it was only good that the BJP got trounced comprehensively, for a win in Bihar would have made their chief Nirankush.

The argument of the ease of governance if the same party ruled both the Centre and the state could not persuade the average Bihari voter. In a discussion when electioneering was in full swing, one of them told a reporter friend, 'For democracy to thrive, it was important to have variety.'

The same reporter told me that the carpet bombing of political messages from the BJP with incessant and relentless full page advertisements in the newspapers left the Bihari voter disturbed: 'Why is it is that they do not leave space for the counter viewpoints? If we do not get to know different political views, how would we make up our mind?'

After the 2014 general election, my friend Satish Deshpande, a scholar of the caste system in India, told me, "It seems Muslims are the new Dalits of India."

The election results of Bihar have brought a great sense of relief to the Muslims, not only of Bihar, but of India at large. They feel included in the Indian project once again. They feel reassured that their Hindu compatriots are not insensitive to their fears and apprehensions about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and would not allow it absolute hold over the Indian political scene.

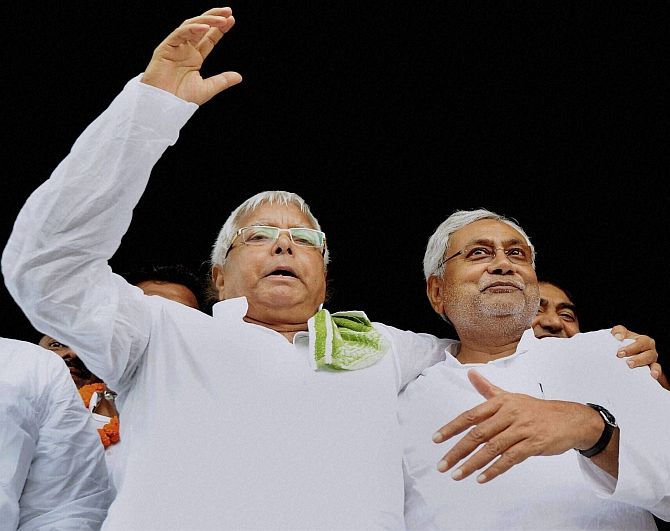

This was not merely a vote against a political party. The leader of the largest political party of Bihar, Lalu Prasad, was very clear: The BJP was not an independent, normal, political party. The real fight was against the RSS, the mind of the BJP. The results were then justly seen as rejection of the RSS by the electorate of Bihar.

It is good for the health of Indian democratic life. Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar along with the Congress stood up for the liberal space when they defended the artists and writers who had started protesting against the hate mongering by the Sangh and the BJP. For this they were termed anti-nationals, traitors, by the top leadership of the government. This win is again a relief for them as now they have a powerful political voice to stand up for them.

The recently concluded assembly elections of Bihar brought out the best and the worst of Indian politics.

First, the best: In a wise departure from its earlier stand of going it alone, the Congress party decided to work under the leadership of Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad. It persuaded them to sit together and overcome their bitterness of more than two decades. It was not an easy job. Nitish had to publically give up his anti-Congress stance, and also collaborate with Lalu Prasad who was unacceptable to his upper caste supporters.

This class of Nitish supporters predicted doom for him for having embraced the devil. Political pundits, his well wishers, advised him against it. He did not waver.

The 'three idiots' could tell their constituencies that the whole is much more than the sum of the parts and politics was much more than a fight for power.

It was also about how to live one's life well, collectively. It is great that Nitish could convince his constituency that he was not being opportunistic. There was something greater at stake and it was a much larger fight.

Another aspect was the sanity that the people of Bihar maintained even in the face of heightened tension, grave provocations to polarise society along Hindu and Muslim lines. The administration and the police force did not lose their Constitutional sense and did not allow communal violence to break out.

Assaduddin Owaisi's All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen had to bite the dust. It was feared that the isolation of Muslims would push them towards a Muslim party. They said, no, thank you! We would be consistent with our past. The Muslims of Bihar and India have always cast their lot with their Hindu compatriots for a secular, peaceful India.

The message from Muslims to their Hindu neighbours is clear: We do not approve of sectarian politics. How is it then that the RSS and its political mask, the BJP, manages to get sympathetic hearing from Hindus?

The significant number of Muslims in the new assembly is also welcome. It is a return of confidence in the secular political parties. Muslims can be accepted as their representatives by Hindus. They can also be universal Indians or Biharis.

The worst part: The prime minister of India and the president of the ruling party of India stooped too low, they actively pitted communities against each other. Theirs was an open provocation to the Hindus to unite against Muslims.

The post election refusal of the defeated BJP to apologise for this divisive, polarising strategy when it said this is all part of aggressive electioneering to bring voters to your side demonstrates that the wishes of its supporters that defeat would bring sobriety to it are naive.

The building blocks of this party are made of hate. The more it continues in power the more damage to the collective fabric of India would be.

The message of the results are also clear: For Lalu Prasad: he cannot forget that it was his family, his brothers-in-law, in his most powerful days who proved to be his nemesis. Two decades have passed since then. They left him for greener pastures in his difficult times. Now, in the moment of his political revival he has to confront his family again.

His two sons are now in the assembly. His daughter is also a professional politician. Would they be able to learn from the past, be sagacious and resist the temptation of being in government.

If Rahul Gandhi can refuse the positions of power repeatedly, why cannot they do it now, when they are still political greenhorns? The credibility of this political formation would depend much on their decision.

On a social plane, the main caste base of the victorious Lalu Prasad has also to behave in a more responsible manner. This is not a mandate for the any caste group to dominate the social space of Bihar.

The Yadavs were being desperately wooed by the BJP. They decided against Hindu-caste-ism. It should not mean, however, a throwback to the earlier era of replacement of upper caste dominance by middle caste dominance.

For Nitish Kumar the message is to be democratic and more political. With the support of the BJP, he had suppressed criticism in Bihar. It was a virtual emergency for the media. Media houses were routinely punished for even small, if ever, instances of critical reporting.

He would also need to change his highly authoritarian way of governance. The all and only powerful chief minister's office-centric governance will have to give way to a real cabinet way of functioning.

The political parties, given the decisive mandate in their favour, cannot afford to fail the people. They have a duty to make it a model for the rest of India. One can only wish that they do it despite themselves.