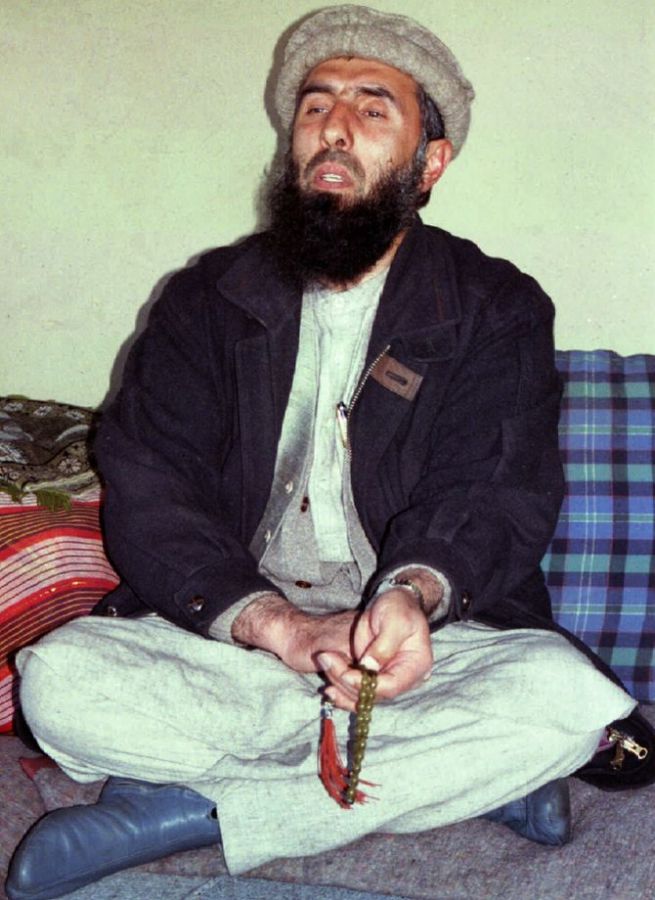

'Gulbuddin is reputed to have harboured a visceral hatred toward India. But I still keep wondering.'

'To my mind, it is impossible for an Afghan -- and a Pashtun at that -- to harbour ill-will toward 'Hindustan,' says Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar, arguably India's leading expert on Afghanistan.

Personally speaking, my 'encounters' with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar have not been pleasant experiences. Their setting was Kabul, and the description of him as the 'Butcher of Kabul' still remains in the attic of memory. But I tend to forgive Gulbuddin.

The year was 1990 when I was on special assignment as Charge d'Affaires to manage the embassy in Kabul. That period was like a long sunset -- full of melancholic hues, while witnessing human suffering from impossibly close quarters.

The Communist regime was on its last legs. The abortive coup attempt by the then defence minister Shahnawaz Tanai to depose President Najibullah came as a rude awakening that the ground beneath the feet was shifting.

When the coup failed, Tanai took a plane and fled to Pakistan to a warm welcome by Gulbuddin. (Don't miss the New York Times report on Tanai's coup by Barbara Crossette, here (excternal link) -- especially, how the incumbent Afghan President Ashraf Ghani viewed it at that point in time in March 1990.)

Indeed, the quicksands of Afghan politics are treacherous and the mujahideen, sensing victory, were knocking at the city gates.

The Russians had already turned their back on Najib. Despite Najib's lingering hopes of Indian support, he soon began negotiating with Pakistan for an 'exit strategy.'

The city went under curfew as dusk fell and it became difficult to distinguish the enemy. And the daily curfew defined our life style.

Gulbuddin was a lurking presence, although based in Peshawar. His guerrillas had taken up positions on the mountain tops surrounding the Kabul valley.

Our embassy residence, where I was quartered, was located close to the airport and often one could hear jets steaming past low, heading toward the mountains, leaving a sonic boom that shook up windows, shattered crockery and set children crying and the dogs barking.

Then, within seconds one would hear the dull thuds as the jets dropped their bombs on positions where Gulbuddin's men were suspected to be.

Some stories from childhood never fade away. Tagore's Kabuliwallah, for instance. I had a Pasthun cook who made terrific kebabs. He had left behind his family in the village and now and then he'd take leave to visit them, leaving me alone.

In the sprawling residence of the ambassador, I'd be all by myself with the security guards. Those were times when the mind would begin stealthily exploring the frontiers of reality.

The thuds in the distant mountains reminded me of another sad story I had read in childhood -- the story of the Dutch settler in the New World, Rip Van Winkle, who, one autumn day, to escape his wife's nagging, wandered into the Catskill mountains with his dog and stumbled upon the hollow which was the place of origin of the thunderous noises he used to hear at times in his village -- and saw a group of ornately dressed, silent bearded men playing nine pins.

Van Winkle didn't ask who they were or how they knew his name, but began drinking some of their Hollands and soon fell asleep. When he awakened, he couldn't recognise himself.

There were shocking changes, his beard was a foot long and the dog was not to be seen. When he returned to the village, he could recognise no one.

In place of the portrait of King George III on the inn's sign hung one of George Washington. Van Winkle later learned that the strange bearded men in the mountains were ghosts of the crew of Henry Hudson, the English sea explorer and navigator of the early 17th century who had vanished a long time ago.

Whenever I heard the distant thuds, I fancied that Gulbuddin's men must be playing nine pins. However, they weren't ghosts. They were indulging in politics by other means.

They reacted unfailingly to every bombing mission by Najib's jets. One fateful Sunday afternoon is still etched in memory.

I found myself working in the ambassador's office in the Chancery after lunch on that Sunday when all of a sudden the ground shook with a shattering sound.

The security guard barged in with panic writ on his face and demanded that we should quickly evacuate to the bomb shelter in the basement. He said a big rocket attack by Gulbuddin's men on the city was beginning.

Huddled behind sand bags, we counted in the next one hour an incessant rain of 27 rockets, all falling in close proximity.

Gulbuddin's men were apparently targeting the interior ministry just across the road, which used to be a prime target of the mujahideen.

It was by far the most vicious rocket attack on the city during my stint in Kabul. There was much destruction. Luckily, no bomb fell on us.

But we were not so lucky on another occasion later when one of Gulbuddin's rockets fell on the embassy compound just as one of our security guards who had finished his duty and was crossing the courtyard near the tennis court to return to his living quarters was directly hit. We delivered to his family his mortal remains in a small gunny bag.

One eventually got used to the sound of the rockets falling on the city, but the suspense took a toll.

Luckily, there was a rumour mill too, which was fairly reliable. Word somehow reached the Kabul bazaar in advance that a big rocket attack was due shortly.

Possibly, Gulbuddin's men on the mountain tops took care to tip off fellow Hezbe-i-Islami cadres inside the city.

Of course, nothing remains a secret in Kabul.

On another occasion, one of Gulbuddin's rockets fell on the ambassador's residence. The ambassador at that time was our present Vice-President Mohammad Hamid Ansari.

The flag car just left the compound when Gulbuddin struck and the ambassador had a narrow escape. The bomb fell on the lovely garden which he nurtured with pride.

The colonel who was our military attaché could stand unseen inside the huge crater that the bomb left. That was apparently a 'mother of all bombs' in Gulbuddin’s inventory.

Gulbuddin used to be a favourite topic of conversation at cocktail parties. We diplomats exchanged notes on the day's score. We gossiped recklessly. We trusted the Pakistani and Turkish colleagues to be the best informed about Gulbuddin.

In that surreal world, when we all scrambled back to the safety of our respective embassy compounds, beating the curfew by a whisker as dusk fell, we'd all be pleasantly drunk and it no longer mattered where rumours ended and facts began.

Gulbuddin is reputed to have harboured a visceral hatred toward India. But I still keep wondering. To my mind, it is impossible for an Afghan -- and a Pashtun at that -- to harbour ill-will toward 'Hindustan.'

We never went after Gulbuddin’s scalp -- and, I know it for a fact that we made persistent attempts (in vain) to establish contacts with him to talk things over.

Even Rasul Sayyaf, leader of the Wahhabi group Ittehad, received me. But it was always 'Nyet' from Gulbuddin.

Yet, he is a pragmatist par excellence. How else could he have successively enjoyed the patronage of Pakistan's ISI, America's CIA and Iran's ministry of intelligence?

Will our folks have better luck this time around now that Gulbuddin has taken residence in Kabul and may receive visitors?

Gulbuddin took his wife and daughter for the ceremony in the presidential palace on Thursday, May 4, marking his return to mainstream Afghan politics. It is not an Afghan practice.

Even an urbane figure like Hamid Karzai never showed up at high-octane political events with family in tow. Has Gulbuddin become 'Westernised'? Who was he trying to impress? General John Nicholson, the US commander in Afghanistan?