With some variations, all regional political formations, whether in power presently or out of it, share some common features: Tight family control of the political apparatus, key members in elected or appointed positions, obvious wealth but not quite known sources of income, and family factionalism, sometimes open and bitter, notes Shreekant Sambrani.

About 10 years ago, I saw on television S S Rajmouli's Magadheera (his film prior to Bahubali). It was the most successful Telugu movie at the time and won critical acclaim as well.

I have since been regularly, almost compulsively, watching many South Indian films, mostly Tamil and Telugu, dubbed in Hindi.

Some are real gems: Jay Bheem, which told in great detail the struggle of an outcast tribal woman and her devoted lawyer to bring to justice arrogant policemen in rural Tamil Nadu, who had 'disappeared' her husband on trumped up charges.

This is the story of K Chandru, who went on the become a justice of the Madras high dourt.

Or the original Vikram Vedha in Tamil, a noir crime film par excellence told by the husband and wife duo of Pushkar-Gayatri featuring the spell-binding performances of Vijay Sethupathi and R Madhavan.

Then there are epics, Bahubali, RRR and Ponniyin Selvan I.

But mostly, they are potboilers, with larger than life heroes (seldom heroines) wreaking vengeance against perceived injustice and their perpetrators, who are either ganglords or corrupt politicians (often a combination of the two) and a supporting cast of a large extended family and townsfolk.

The plotlines remain much the same most of the time, the crimes vary, but the outcome is always the prevailing of the hero, often even in politics.

The novelty is in treatment and one marvels at how many combinations of violent action and topical references the creators of these films can think of.

(Parenthetically, a hint to the Bollywood biggies, stars and producers, who remake these films in Hindi and fail miserably in this quick fix. Don't do remakes; engage the successful Southern content creators instead to come up with 'original' formula scripts which will light up Hindi screens.)

Consider this sample scenario:

The founder of the clan, let's call him A, is relatively poor and unskilled. He joins a local mine, among the largest of its kind in India.

His career takes off and he acquires a share in the mine. He becomes a leader of his community, is elected as sarpanch, and gets caught up in the violent interplay between caste, politics and mining, the source of money and wealth.

He is eventually killed by a bomb, obviously at the hands of his opponents.

His eldest son, call him B, becomes a doctor, joins the ruling national party, gets elected to the state assembly and Parliament and eventually defeats the strong regional party ruling the state.

He becomes the chief minister and is well-liked because of his populist measures.

He dies in a helicopter crash, shrouded in mystery. His son, our hero, call him C, expects to succeed his father as the chief minister, but the party nominates someone else.

C quits the party and starts his own and wins a landslide victory, by invoking the memories of B, after whom the new party is named.

One of the hero's uncles, no 1 (B's brother), remains in the national party, but is defeated in the election by the hero's mother, the grieving widow of B.

Uncle no 1 quickly sees the folly of his ways and joins C.

Meanwhile, uncle no 2, B's cousin, has gotten close to the nephew, now chief minister C and wants his own son to be elected locally. Uncle no 2 sees uncle no 1 as the main roadblock.

Soon, uncle no 1 is found dead in his home (all homes are large and staffed by many retainers).

It is given out initially that he suffered a heart attack, but subsequently revealed that he was murdered, beaten with blunt instruments and attacked by scythes (a very common weapon in our films) which led to profuse bleeding and eventual death.

C vows revenge and announces investigations.

Three years later, a plot comes to light: Uncle no 2 had conspired to get uncle no 1 killed by hiring a gang.

The agreed fee was Rs 40 crore, with Rs 5 crore guaranteed to each participating goon. Finally, uncle no 2 is arrested.

But that's not the end. A sequel is hinted at.

The state B had ruled was split into two after B's death, with the connivance of the national party.

C became the chief minister of the larger half, but the smaller, more glamorous, half is ruled by another clan, whose head has ambitions beyond his state.

C has his eyes trained on the breakaway state (presumably because he thinks it is part of his patrimony) and appoints his sister the head of his party in that state.

The sister mounts an agitation in that state, supposedly with the blessings of the national ruling party, which replaced the earlier national party nearly a decade ago.

Watch this space for further developments!

Or consider another storyline:

The leader of an upper caste organisation, call him X, floats a new party and gets his wife elected to Parliament, in open defiance of the pro-reservation backward caste chief minister.

X becomes a local hero. His two acolytes, Y and Z, brothers who are relatively small-time toughies, also have political aspirations.

Y is killed, his associates suspect with police connivance.

His funeral procession is conducted in gravely tense atmosphere.

The district magistrate of a neighbouring district crosses the procession in his official car on his way home.

The mob attacks the car, and drags out the official (who happens to be a Dalit).

X screams at the grief-crazed Z who is leading the funeral, 'Kill the bastard and take your revenge!' The mob goes berserk, the officer is beaten and shot at, and left bleeding on the road.

Eventually, the police take him to a hospital where he dies.

The pro-reservation chief minister swears that justice will be done.

X and some of his followers are tried, convicted and awarded the capital punishment. The Supreme Court commutes it to life imprisonment.

Decades pass, the old chief minister is caught in many scams and is now old and feeble.

His long-time adversary, also an advocate of backward caste reservations, is now the chief minister, after many back-and-forth political manoeuvres.

He is fully focussed on the national political scene.

He decides to modify the state prison rules to enable X to walk out of jail.

X emerges as some sort of messiah to his upper caste group.

In a twist absolutely worthy of potboiler scripts, the old chief minister's son is now the deputy to the new one and his chosen successor. Presumably, he was involved in countermanding his father's earlier decision.

Too fanciful, you say? You are absolutely right! Not even the soaring imaginations of the gifted writers of regional cinemas could dream up of such plots!

But they are parts of the current headlines.

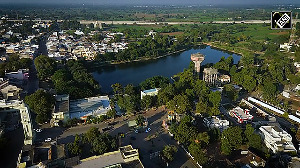

The mining clan referred here is the Yedugiri Sandinti family of Andhra, the chief ministers being Dr Y S Rajasekhara Reddy of the undivided Andhra Pradesh and Y S Jagannath Reddy of the present truncated Andhra Pradesh.

Uncle no 1 is Y S Vivekananda Reddy and Uncle no 1 is Y S Bhaskara Reddy.

The neighbouring state is Telangana and Y S Sharmila is the president of the YSRCP Telangana unit.

The full story appeared in The Indian Express on April 26.

The other story refers to the release of Anand Mohan in Bihar, who was convicted of the murder of the IAS officer G Krishnaiah.

His acolyte Chhotan Shukla was killed in 1994.

Mohan is supposed to have goaded Chhotan's brother Bhutkan to attack Krishnaiah.

The Bihar chief minister then was Lalu Prasad Yadav.

The present chief minister is Nitish Kumar.

He authorised the modification of the rules on prisoner release, presumably with the consent of his deputy Tejashvi Prasad Yadav, Lalu's younger son.

Anand Mohan is feted as Sher-e-Bihar. Mrs Krishnaiah and her daughters have appealed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to intervene.

The action of the Bhupendra Patel (Modi's successor twice removed) government of Gujarat resulting in the release of the convicts of Bilkis Bano's rape and murder of others in 2002 is being challenged in the Supreme Court.

This story also appeared in The Indian Express of April 27.

To conclude from the above that life imitates art would be both trite and not entirely true.

What is obvious is that events such as those surrounding the ruling family of Andhra Pradesh, the YS clan of Kadapa district, actually inspire screenwriters and directors to base their films on the political and family events making the headlines.

The reel life is thus inspired by real life, and not the other way around.

This is as true of the Amitabh Bachchan starrer Deewar being inspired by the story of the smuggler Haji Mastan as it is of today's Telugu and Tamil potboilers.

But the real point is something else. From modest beginnings, the YS clan rose in two generations to the level that even relatively minor members could offer huge sums to hired guns for political assassinations.

Lalu Prasad grew up in cattle sheds, but his youngest son now has at his sole disposal a swanky bungalow in a posh New Delhi neighbourhood, technically the office-cum-guest house of a company in which he has a major interest.

These are not the only instances of the family political enterprise leading to amassing of wealth.

The other major political headline of the last week was the passing of Parkash Singh Badal of Punjab.

While acknowledging the stellar role the Akali Dal patriarch played in Punjab politics of the last seven decades, including five turns as its chief minister, standing firmly against radical separatists in India and abroad, it must also be acknowledged that he made his son Sukbir Singh his deputy in the cabinet and the party president.

The daughter-in-law Harsimran Kaur has been a member of Parliament and a minister in the Narendra Modi governments.

Other kin, nephews, in-laws and cousins have been parts of Badal governments and top leadership of the party.

The senior Badal began modestly, as the sarpanch of his village 75 years ago and aspired to be a government official.

But now the Badals are among the wealthiest families of the state.

Former chief minister Amrinder Singh had claimed that the Badal wealth ran to billions, held in India and abroad, an allegation that has not been convincingly rebutted.

With some variations, all regional political formations, whether in power presently or out of it, share some common features: Tight family control of the political apparatus, key members in elected or appointed positions, obvious wealth but not quite known sources of income, and family factionalism, sometimes open and bitter.

The New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote on April 27, saying that Donald J Trump possessed a kind of nihilism that you might call amoral realism.

This ethos is built around the idea that we live in a dog-eat-dog world.

The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Might makes right. I'm justified in grabbing all that I can because if I don't, the other guy will. People are selfish; deal with it.

He added that this ethos was central to the approach of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping as well.

It allowed them to be selfish, dishonest, cruel and arrogant all at the same time.

In the amoral world they inhabit, these are not vices but survival skills.

They are not restrained by codes of personal honesty and respect for the rights of others.

He may as well have been writing about the many family fiefdoms and satrapies that dot the Indian political and economic ecosystems.